Editor’s Forward:

This is a story that started as a dream, that became therapy, that became a metaphor, that became a story, that became permission for having closure. The names have been changed to protect the innocent. The guilty know who they are, and nothing can ever change that. The truth is, once the river takes you where it wants you to go, you can’t easily go back. If you try, the places that you know will never look the same again.

They found the river the way people find shortcuts they don’t deserve—by following a hunch, then a fence line, then the angle of a shadow that suggested there must be a way through. The city had poured the water into a concrete groove years ago and called it drainage, but to Maris it looked like a road that had forgotten how to hold cars. Tapered banks sloped toward a shallow runnel of brown water, and on either side trees tried to apologize for the culvert by leaning over it with leaves. You could see the backs of buildings through the branches—brick faces, metal doors, dumpsters like punctuation marks. It was the part of the city that pretended not to be seen.

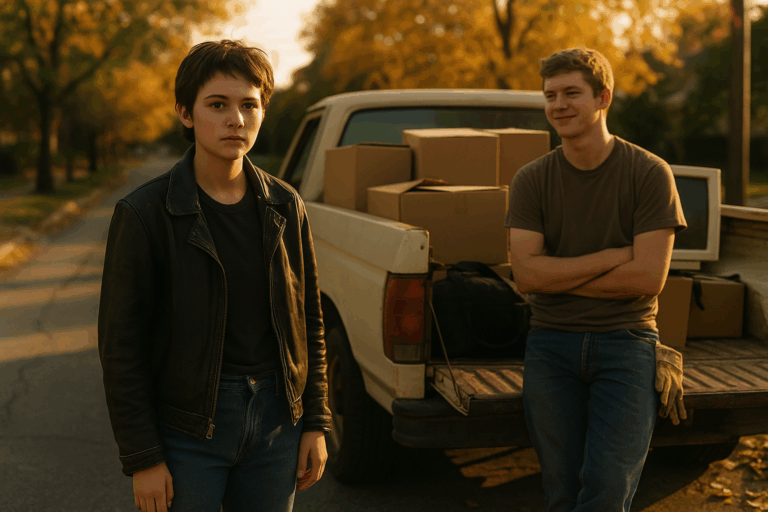

Maris and Cass walked along the dry shelf where the water didn’t reach. It was late afternoon and the light slid between branches in narrow panes. The regular world ran parallel a block away—traffic, a bus hiss, a child yelling in a park—but here the air felt held in place. They were on their way to nowhere in particular, which is when people are most likely to step behind the curtain.

“Do you ever feel like this is the actual map,” Cass asked, “and the streets on the other side are the legend no one reads?”

Maris smiled without looking over. “You say that like you want it to be true.”

“I want to walk somewhere that isn’t designed for me.”

They had come here once or twice before, during summers when idleness felt like a craft. It was not a place you took photographs of. The city kept it utilitarian; life had stained it interesting. Shopping carts rusted into the silt. A bicycle frame clung to a sapling as if ashamed. There were the kinds of shoes that have lost their owners and become their own species.

What made today different was the boat.

They saw it where the culvert bent, half in shadow, tied with tired rope to a piece of rebar that rose like a question from the concrete. It wasn’t much of a boat—flat-bottomed, scuffed, metal rales dented like a jaw—but it floated with a stubborn, unbeautiful grace. There was a loop of line attached to a cleat, and an aluminum oar lying across the bench like an invitation someone had forgotten to send.

Cass stopped first. “No.”

Maris kept walking until she stood close enough to nudge the hull with her foot and feel the answer through her shoe. Float. “You don’t even know what I’m going to say.”

“You’re going to say it’s a sign.” Cass’s mouth was a thin line that tried to be a smile and failed. “You’re going to make it into myth.”

Maris was going to. She could feel the narrative take shape like a current you don’t see until it’s tugging at your calf. But the other truth rose with it, honest and unembarrassed: she wanted to know where the river went once it stepped out of this daylight.

She looked up. Ahead, the culvert narrowed and the concrete walls rose, shouldering aside the trees, the air blue-darkening into a low arch where the whole waterway slipped under a city block, then another. There were places like that all over town—underpasses and tunnels and siphons—but this one, today, held its mouth open like a door someone had meant to close and hadn’t.

“It’s not a sign,” Maris said, and heard the lie catch on her tongue. “It’s—opportunity.”

“Same thing.” Cass’s voice had that careful calm people use when they love you and also want to shake you. “You have no idea what’s down there.”

“Neither do you.”

“Exactly.”

Maris put a hand on the pitted gunwale and felt the give of metal, the slight see-saw of water under weight. The boat smelled like damp rope and river skin. Someone had painted its name on the stern years ago and time had rubbed it nearly blank. If you squinted you could make out a shape that might have been an R.

Cass folded their arms. “We are not children. We don’t get to pretend this is a creek in a cartoon.”

“Children wouldn’t go.” Maris said it softly, which was worse.

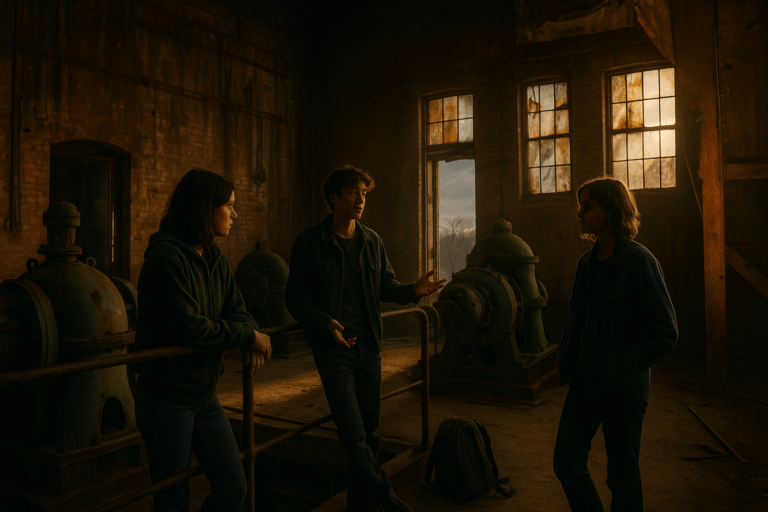

For a while they argued the way people argue when there’s love on both sides and fear on one. Cass enumerated disasters: a grate that would grind the boat and bodies both; a sudden drop; a colony of rats with the sense of entitlement that comes from uninterrupted tenure. Maris countered with pragmatics: the current was slow; the tunnel looked sizable; there was as much danger in the city above as below, only we agreed to forget it there.

“You’re asking me to bless a bad idea,” Cass said finally, hands open like a benediction withheld. “I won’t stop you. But I won’t get in.”

There are decisions that can be discussed and decisions that are already made in the body. Maris felt it: the peculiar lightness that means a thing is going to happen and your mouth will either be brave for it or not. She put one foot in, then the other. The boat accepted her weight like a sigh and then steadied. She untied the rope, laid it in coils, and used the oar to push off the concrete with a hollow sound that echoed under the bridge like wood on bone.

“Please,” Cass said. It was not a dramatic word. It was the word people use to pull you back from an edge they suspect you were born to walk.

Maris met their eyes. Cass had the particular steadiness of people who stay, who do the long labor of turning a life into a place where others can rest. Maris loved them for it, and she understood, without surprise, that it was exactly the quality that would keep them on shore.

“I’ll send you a postcard,” Maris said, because it was easier to be glib than tender. Then, softer: “If there’s a way back, I’ll find it.”

“You won’t,” Cass said, and somehow made the words a blessing. “That’s why you’re going.”

The current took hold as if it had been waiting politely. Maris turned the bow with a few awkward pulls and let the boat align itself with the culvert’s slow pull toward the tunnel. Behind her Cass stood very straight, hands in their jacket pockets, an ordinary figure made holy by the way afternoon light loved their hair. Maris felt both held and released. She raised a hand and watched her friend raise one back, and then the turn took the world and the opening swallowed both of them in their separate directions.

The tunnel accepted her without ceremony. Concrete smoothed into bruise-colored brick, then to sections of corrugated metal that made the sound of rain even when it was dry. The oar thocked against the hull. Maris tucked it beside her and tested the water with her hand. It was cold in the way bodies of water inside cities are cold, a particular blend of geology and runoff and the secrets of basements. The light fell away behind her in increments, and ahead of her the dark was not quite dark, because somewhere, always, a storm drain leaked a blade of day.

There were other mouths, cut into the tunnel at right angles, feeding this one. Some were large enough for a child to crawl into; some were slots; some were just holes in the logic of the brick. Water poured from them, thin waterfalls that stitched the tunnel’s face with silver. Maris could have chosen none of them even if she’d wanted to. The boat rocked where the feed met the flow. She rode it where it wanted.

In that dim, time became water, and Maris’s mind did what minds do when their hands have nothing to arrange: it filled with the rooms she’d left behind. A kitchen with a kettle she always forgot on the back burner. A closet that smelled like pennyroyal and old paper. A bedroom where someone else’s breathing was a metronome that kept her contradictory hearts in time. There had been years of carrying—not all bad, not even mostly bad, but weight nonetheless—and the boat moved under her like the idea that she could set something down and have the world not punish her for it.

She thought of the last ten years and felt an ache at the base of her skull. That ache had taught her to listen for crises the way mothers listen for coughs in the night. It made quiet feel like a cliff. But here in the tunnel the quiet was loud and inescapable, and nothing arrived to end her. Maybe, she thought, the river took what it was owed and left the rest.

The ceiling rose without her noticing exactly when. The air changed—cooler, less insistent. The sounds spread out. The brick gave way in places to poured concrete stained with ferric weeping, then to rough stone, as if the city had grown backwards and only now remembered its bedrock. The boat’s scraping diminished; the current widened its shoulders. The tunnel became a channel, and then, with a shift she felt in her teeth, an opening.

She came out into light that felt like relief held in suspension. The roof of the tunnel framed a slice of sky like a sky had snuck indoors. The water spilled her into a basin ringed with low cliffs, stone rough and honest, and there were strips of sandy shore the color of unambitious bread. Beyond, the basin resolved into a larger body—more than a river, less than sea—turned silver by sun. Boats far off cut thin lines the way thought cuts through habit.

Maris angled toward the nearest pale crescent and let the hull drag itself onto the sand. The sound of metal on grit was both rude and right. She stepped out and the ground wobbled under her feet, not because the ground was unsteady, but because she was remembering how to walk. The air smelled not exactly clean but simpler, and there was wind. Above the cliff, houses watched.

They were old townhouses turned toward the water like listeners. No two alike, but kin—brownstone faces, arched windows, the kind of lintels that have seen argument and apology. Ironwork that had outlived fashions and owners. Stairs that had been swept by hands with a hundred different reasons to keep sweeping. Maris looked up at them and felt a sensation that was not surprise and not homecoming, but adjacent to both. Civilization after the underworld. Rules after weather. She laughed once, a breath’s worth of disbelief, and then climbed.

The path to the houses was not a path until her feet insisted. Grass took her ankles like small hands. The cliff was manageable if you were stubborn. Maris had been called stubborn as a compliment and as an accusation, and both had always fit. At the top, the nearest townhouse had a door like a mouth that had made peace with speaking.

It was unlocked. Of course it was. Dream logic and city negligence sometimes hold hands.

Inside, the temperature changed the way it does when a building has retained the day and is reconsidering whether to give it back. The hallway smelled faintly of old varnish and something citrussy attempting to atone. A hat tree stood as if expecting to be useful. There were framed photographs on the walls, black-and-white faces with the smug immortality of pictures that have survived more moves than marriages.

Maris’s shoes sounded too loud on the floor. She slipped them off out of respect for ghosts and set them neatly beside the door. The living room admitted light in a practiced way, filtered through lace that made the sun feel like memory. On the mantle, a clock that had long ago given up keeping time still kept the posture of something that once did. A kettle sat on the stove in the adjoining kitchen. When Maris touched it, it retained a whisper of warmth it could not have earned, unless this was a house where the rules were gentle with people who’d just come out of tunnels.

There were photographs on a low table. Not the stiff, formal ones on the wall, but snapshots in color, oversaturated like memories that have been retold too often. Maris recognized none of the faces and all of the occasions. A birthday where the cake had just become a slice of itself. A summer day with a dog that had opinions about sprinklers. A dinner with too many chairs for the number of people who’d stayed; everyone smiling with the ferocity of an argument postponed. In one picture, a woman who was not Maris had Maris’s hands. In another, a crowd made room for someone just outside the frame, the way a family shifts to include a person it has decided to love.

On the kitchen table was a letter. Her name was on the envelope in a hand that could have belonged to an aunt or a classmate, the part of handwriting that remembers school and the part that remembers holidays. MARIS, it said, with the confidence of a person who expects to be read. She did not recognize the script, which did not matter to the part of her that had known there would be a letter somewhere. The paper inside was thick enough to feel like intention.

It read:

You came through.

I don’t know who told you there would be a map back, but they meant well and they were wrong.

If you try to return by water, you will become someone else’s story.

If you want to visit the place you left, walk. Bring bread. Expect not to be recognized, and be gentle when you are.

There’s tea in the blue tin by the stove. There’s a blanket in the chest by the window. Both have been waiting for you longer than seems possible.

– L.

Maris waited for the hairs on her arms to stand; they didn’t. She felt something quieter, like a muscle unclenching without permission. She made the tea and it tasted exactly like tea. She carried the mug to the window and sat on the floor with the blanket, which smelled faintly of cedar and something she decided to call pepper even if it wasn’t. Outside, the basin held small boats as lightly as a thought holds an idea before it lets it go.

Cass’s face rose in her, because love is not unmade by tunnels. She pictured their hands in their jacket pockets, the posture of a person choosing the long labor of the shore. Maris knew, with the accuracy of certain kinds of certainty, that if she walked back the long way, she would find streets that recognized her gaits, and also streets that had learned new names for themselves in her absence. She knew there would be people who would take her in as if nothing had shifted, which would be a kindness and a lie. She knew there would be others who would say, without reproach, “You look different,” and mean: you put something down and grew taller.

The house did not ask anything of her. Its rooms were the size of thoughts she could stand to have. In a bedroom there was a wardrobe with a mirror that didn’t startle her. In a study there were books with the spines broken in places she would have broken them. The letter said both less and more than she wanted, which is often how permission arrives.

She slept. When she woke, the light was a different flavor of ordinary. She ate a heel of bread that had no courtesy to be fresh and was therefore perfect. She wrote a note on the back of the letter, because it felt correct to leave something behind for the person with the steady hand.

Thank you, she wrote, for keeping the kettle honest.

If you see Cass in this city—if this is a city with versions of everyone—tell them I took the water and I’m taking the land, too.

Tell them I brought bread.

– M.

She folded it and put it back in the blue tin with the tea, because hiding things in plain kindness is its own magic. Then she put on her shoes. The door was light under her palm. The stairs down to the street felt like a conversation she didn’t mind having.

At the cliff’s edge she paused. The basin looked like a plate someone had set down in a hurry. The tunnel mouth was still there, a square of dark that meant what it meant. The boat sat where she’d left it, slightly higher because the tide had opinions. She could have pushed it back into the water and made drama of reentry. She could have walked the shore, found a road, followed the lines of the city until they intersected the roads she knew. Both were true. Only one would pretend to be reverse.

She chose the path that required ankles and patience. The cliff did not complain. The grass held her as if she were a breath it had been expecting. She found a street that believed in addresses. She found a bus stop where no one looked like a metaphor. She stood there long enough to feel foolish and then long enough to feel fine.

On the bus, a child pressed her face to the glass and narrated the world to no one: tree, dog, man with hat, house like cake, woman like cloud. Maris smiled. A few stops later a woman offered her the leftover half of a sandwich with the maternal entitlement of someone who takes it personally when strangers don’t eat. Maris took it. It was ham. It tasted like courtesy in a sourdough jacket.

The route numbers grew familiar, then strange again, then familiar in a different way. The city is good at remixing itself to see who’s paying attention. When Maris got off and walked, the streets around the culvert were not the same streets, because she was not the same walker. She found the fence line the way you remember a song’s chorus after forgetting the verse. She did not climb over. She stood and listened.

There was no drumbeat of emergency on the air. In the gap where panic used to live, there were plans. Coffee in the morning. Teeth brushed before bed. A neighbor’s laundry thumping the dryer like a heartbeat in the house next door. Work to find, work to make. A limb to rig off a tree with something like elegance. The ordinary, miraculous list that accumulates in the absence of catastrophe until one day it turns into a life.

She did not go looking for Cass immediately, because love that respects itself understands sequence. But she texted a photograph of the letter’s envelope, her name written in that decisive hand. No caption. Cass would know exactly as much as Maris could say: I went where you told me not to, and I was right to, and you were right not to come.

A few minutes later, her phone buzzed. Cass had sent a picture in return: a patch of sky caught between two narrow buildings, laundry lines making music out of wind, a corner of a café awning the color of people who change their minds and call it growth. No words, just witness.

Maris put the phone in her pocket and walked toward the sound of the world going on. Behind her, the river took what it was owed. Ahead, the land made room for feet.

And if, at night, she woke and heard in the plumbing the echo of tunnels and of water negotiating with stone, she did not mistake it for warning. She got up, put the kettle on, and let the house repeat back to her the one truth she had earned the right to believe:

There is no shoe left to fall. There is only the floor, waiting, and the practice of walking across it.