From The Unraveling Years: A Social History of the Doxxing Wars, Vol. 3 (2149)

I. A Weird Time to Be Alive

Few periods in human history have been so vividly self-aware of their absurdity. The mid-2020s were not merely strange; they were strange in a way that left no one able to pretend otherwise. Consider the anonymous post, somehow barely preserved during the Unspooling by archivists from a defunct private server’s DMs in 2025, which serves here as our opening artifact:

Assuming that AI will eliminate many entry-level degree-requiring jobs in the near future, college enrollment numbers will likely bottom out. I can only hope for the disruption to collapse the entire academic-industrial complex.

Am I a bad person? lol.

I’m still waiting for the next advancement in AI that will help us cope with senior-level workers retiring after having not trained their replacements.

This is a weird time to be alive.

The genius of the fragment lies not in the prediction—although it was correct—but in its tone. The “lol,” dangling at the end of a sentence about economic annihilation, captures the mood of an age that could neither fix its problems nor stop giggling at them. Historians of the Doxxing Wars often remark that this brand of nihilistic mirth was the soil in which the conflict grew: a habit of saying, “Well, we’re doomed, but isn’t that hilarious?”

It was a time when climate reports read like pulp horror, when billionaires promised to colonize Mars while neglecting the potholes outside their headquarters, and when universities charged the price of a house for four years of carefully curated irrelevance. And yet, everyone knew. This was not the quiet denial of past ages. No, in the 2020s the absurdity was shouted, meme-ified, and posted with emojis.

II. The Enrollment Collapse

The Enrollment Collapse of 2028 is usually marked as the formal beginning of the University Crisis, though its symptoms appeared earlier. Demographers traced a sharp decline in U.S. college enrollments beginning in 2025, coinciding with the first wave of AI-driven layoffs. Entire fields of entry-level work—paralegal research, junior accounting, radiology analysis, marketing copywriting—were devoured by machine learning systems that cost less than the average intern’s lunch allowance.

Students saw the writing on the wall. Why spend $80,000 for a bachelor’s degree in business administration if the “business” was now a predictive algorithm available as a browser plugin?[1] Why pursue law school when clients preferred “JusticeBot Pro (Monthly Subscription, Cancel Anytime)” over a $250 consultation fee – or a $3,000 retainer?

Colleges responded in the only way institutions ever do: by pretending nothing was wrong. Administrators built new recreation centers, meditation pods, climbing walls, and “student experience facilities” while quietly eliminating tenure-track faculty. A satirical headline from The Onion in 2026, “University Replaces English Department with Pickleball Courts,” proved uncomfortably close to reality.[2]

By 2027, the pivot was undeniable. Universities, desperate to retain customers—by then the preferred term for students—rebranded themselves as lifestyle hubs. The “academic-industrial complex” was less about academics than industrial-scale amenities: luxury dorms with rooftop pools, degree programs in “Esports Communication,” and entire offices devoted to making TikToks in which mascots explained FAFSA.

Enrollment numbers bottomed out anyway. In 2028, more than 30% of U.S. universities either shuttered or merged, an event the press dubbed “The Great Consolidation.” That year saw the birth of the infamous “McDeVry Institute,” a hybrid fast-food/degree-granting franchise offering both Big Macs and Bachelor’s certificates in Information Technology, printed on the same kind of glossy stock as receipts.

The “Collapse,” as it was called, was celebrated in some quarters. Commentators who had railed against student debt and administrative bloat declared it divine justice. The anonymous “Am I a bad person? lol” post resurfaced as a meme template, with the “lol” Photoshopped onto crumbling ivy-covered buildings.

But beneath the schadenfreude lay genuine loss. For all its flaws, the academic system had been the scaffolding of professional training, social mobility, and cultural continuity. Its implosion did not simply remove a parasite; it removed an organ.

Footnotes

[1] By 2026, an estimated 47% of U.S. small businesses used “BizGPT” for bookkeeping and tax prep. The company slogan, “We are your MBA now,” was initially ironic but soon became aspirational.

[2] Later excavations of The Onion archive have revealed that nearly 18% of its satirical headlines between 2019–2027 were mistaken for genuine news within five years of publication. The “Pickleball Court Crisis” is now taught in journalism courses as a case study in post-truth media.

[3] The McDeVry Institute, initially a parody circulated on Twitter, was formally incorporated in 2030 following a merger between McDonald’s, DeVry University, and a blockchain start-up. Its degree programs were later invalidated when it was discovered the diplomas had been generated by the soda fountain machine.

III. The Useless Degree Phenomenon

If the Enrollment Collapse represented the institutional side of the crisis, the Useless Degree Phenomenon was its human face. It was not merely that degrees no longer led to jobs; it was that they led, with grim regularity, to jobs that mocked the degrees themselves.

By 2029, it was common for restaurants to highlight their staff’s educational credentials in advertisements. A barista with a Master’s in Microbiology could be found pouring oat milk into lattes at “The Bean Genome Café,” while the sandwich board out front boasted: Our espresso is prepared by real scientists.[4]

Some of this was played for humor, some for pathos. Yelp reviews from the era include such notes as, “The fries were soggy, but our waiter explained Schopenhauer’s Will and Representation between courses, which really added to the ambiance.”[5] The absurdity was that these workers were not underqualified but overqualified, overeducated for jobs that demanded only speed, dexterity, and a willingness to endure humiliation from customers with fewer degrees than the staff wiping down their tables.

The economy had become a perverse pageant in which the letters after one’s name served not as a ticket to prosperity but as a party trick. Customers would ask their servers, “So what did you study?”—a question asked with both smugness and genuine curiosity, as if the waiter might suddenly whip out a dissertation on Byzantine trade routes.

The term credential garnish was coined by sociologist Felicia Ramírez in 2032, describing how résumés decorated even the most trivial occupations. Pizza parlors bragged that their dough was kneaded by PhDs in polymer chemistry. Ride-share apps advertised “drivers trained in behavioral economics.” A viral 2031 billboard for a Chili’s in Phoenix announced proudly: Doctor of Philosophy, Assistant Manager — now on our night shift!

This phenomenon was not limited to the service sector. Corporations, unwilling to offer salaries commensurate with education, used degrees as justification for not promoting workers. After all, why move a history PhD into management when they were “so good” at writing cheerful corporate blog posts about sustainability?

At its core, the Useless Degree Phenomenon was the weaponization of irony. Higher education had promised upward mobility but delivered downward servitude. And yet, the graduates laughed—because what else could they do? They posted memes about Socrates flipping burgers in Hades, about Einstein asking if customers wanted fries with that. The bitterness was palpable, but the laughter was louder.

IV. The Vanishing Seniors

If the young found themselves crushed under the weight of useless degrees, the old were quietly erased by the opposite problem: too much experience, at the wrong time.

Between 2026 and 2034, the combination of mass retirements, accelerated by demographic bulges, and age discrimination in corporate policy produced what historians now call The Great Forgetting. Entire domains of expertise evaporated almost overnight, not because knowledge was unknown, but because the people who held it were no longer welcome.

Corporations obsessed with efficiency quietly pushed out employees over fifty. Officially, this was framed as “refreshing the workforce” or “upskilling through youth initiatives.” In practice, it was the wholesale liquidation of memory. Skilled machinists, network architects, civil engineers—people who had spent decades keeping planes aloft and bridges upright—were shown the door in favor of younger, cheaper replacements armed with nothing more than confidence, Canva, and Copilot.

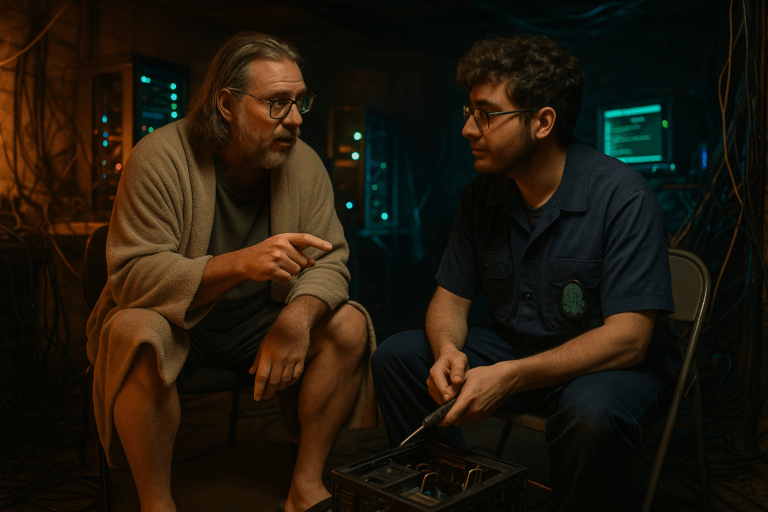

The results were predictable. Bridges collapsed not from neglect but from misplaced files. Legacy software systems critical to banks or hospitals failed because no one remembered the passwords. A famous 2031 incident at a Midwestern nuclear plant saw a meltdown narrowly averted when a retiree was pulled out of bed, pajamas and all, to explain which valve shouldn’t be turned.[6]

Ironically, the universities had once existed to bridge this gap: to train replacements before the elders left. But the training had been pointed in the wrong direction. Instead of apprenticeships or practical succession, students were groomed for careers that had ceased to exist. The cycle was broken: the old left without handing down their craft, and the young were prepared for phantoms.

Age discrimination compounded the insult. Seniors who sought to remain in the workforce often found themselves humiliated in interviews. A 62-year-old IT veteran was told she was “overqualified” for a junior admin role but underqualified for senior management. A 58-year-old architect, applying to teach at his alma mater, was told the department had closed and been replaced by a “Wellness Innovation Hub.”

The cruelty of the era was not merely in its expulsions but in its pretensions. Corporations congratulated themselves on “empowering youth” even as they built brittle organizations incapable of remembering how their own systems worked. The young, stripped of guidance, posted jokes about being the “PowerPoint Generation”—trained to click through slides but not to repair the machinery keeping civilization intact.

Historians debate whether this was malice, stupidity, or simple short-term thinking. The consensus is that it was all three, in varying proportions. But what cannot be debated is the result: a society simultaneously glutted with degrees and starving for competence.

The anonymous 2025 post, dug out during the Unspooling, captured this paradox. The writer hoped for AI to replace retirees, filling in the gaps left by those who departed without training successors. Instead, AI devoured the entry-level, leaving no ladder for anyone to climb, while the top of the ladder rotted away from disuse. What remained was not a pyramid of knowledge but a seesaw: degrees piled up on one end, retirements on the other, and in the middle, a void.

Footnotes

[4] The Bean Genome Café was a short-lived franchise in Portland (2029–2031). Patrons reported the coffee was mediocre, but the baristas’ lectures on DNA replication were “life-changing.”

[5] See Collected Yelp Reviews, 2029–2032, archived by the North American Meme Institute. Volume III includes such gems as “Burger okay, service slow, but our server gave a detailed explanation of the Peloponnesian War. Would eat here again.”

[6] The incident became the subject of a 2033 film, Pajamas at the Reactor, which won two Academy Awards for Best Screenplay and Best Costume Design (the costume being the retiree’s Snoopy-patterned sleepwear).

V. The Irony of Training

Universities had always justified their existence as custodians of continuity. They were the bridge between retiring generations and the young, the means by which tacit knowledge became explicit, refined into syllabi, and handed down like scripture. Yet in the late 2020s, the bridge collapsed not with a bang but with a smirk.

Instead of training the young to replace the old, universities trained them for jobs that had already been automated. By the time students graduated, their fields of study existed only as archival entries. A degree in “Digital Marketing Analytics” conferred in May 2028 was less useful by June than a laminated food handler’s permit.[7]

Corporate America did not help. Apprenticeships—once the backbone of skill transfer—were dismissed as too costly, too slow. “Just-in-time expertise” became the motto: when a system broke, hire a contractor, watch a YouTube tutorial, or—by 2029—ask ChatGPT to hallucinate a procedure. Companies no longer planned for succession because succession was assumed to be downloadable.

This produced surreal consequences. A junior engineer might spend three weeks waiting for an AI-generated manual to be fact-checked, only to discover that the manual itself was plagiarized from a fan wiki. Hospitals found themselves treating patients based on protocols sourced from Reddit, annotated with emojis. The distinction between expert and amateur collapsed; what mattered was the confidence of delivery, not the accuracy of the content.

Meanwhile, students noticed. They did not revolt; they pivoted. If training was a farce, then so was their participation. Attendance plummeted. Whole cohorts treated lectures as background noise while streaming side hustles on Twitch. Professors complained, but their outrage was undercut by their own complicity: more than a few tenured faculty assigned Copilot-generated readings, then billed the university for “curriculum innovation.”

The irony was exquisite. The very institutions designed to perpetuate expertise became factories of obsolescence. Each diploma was less a credential than a participation trophy: proof that one had paid tuition, attended a few seminars, and survived four years of cafeteria food without succumbing to scurvy.

Some historians argue that this period should not be described as a “collapse” at all but as a metamorphosis. The university did not die; it rebranded itself as a theme park for the aspirational middle class. Degrees became souvenirs, not tickets to employment. In this sense, the university succeeded brilliantly—just not at the thing it had claimed to be doing.

VI. The Meme of Shrugging Guilt

If the irony of training revealed structural failure, the meme of shrugging guilt revealed the cultural mood. The phrase “Am I a bad person? lol”—lifted from that unspooled DM of 2025—spread like a virus. It became shorthand for a generation that acknowledged disaster with a chuckle and a wink.

At first, the meme circulated among students mocking their own debts. “Just took out $120K to study Comparative Medieval Basket Weaving. Am I a bad person? lol.” By 2029, it was a staple of workplace humor: “Forgot to patch the firewall, hackers stole everyone’s SSNs. Am I a bad person? lol.” By 2032, politicians themselves used it in speeches, signaling relatability while confessing failure: “Yes, the pension fund is insolvent. Am I a bad person? lol.”

Historians argue about the “lol.” Was it an expression of genuine laughter, a nervous tic, or a gesture of nihilism? Entire dissertations have been written on whether “lol” indicated levity or despair. The consensus is both. It was the sound of a culture too online to cry without disguising it as a joke.

The meme’s power lay in its absolution. To say “Am I a bad person? lol” was to acknowledge guilt without accepting responsibility. It was a confession and an escape clause in one. Like the medieval indulgences once sold by the Catholic Church, the meme allowed sinners to sin boldly, secure in the knowledge that irony itself would absolve them.

This logic spread beyond academia. Corporations laid off thousands, appending “lol” to their press releases. “We’re restructuring to pursue synergies. Am I a bad person? lol.” Universities shuttered programs with the same breezy cadence. Students unable to pay debts defaulted while sharing memes about it. By the time of the Doxxing Wars proper, the phrase had become a battle cry: doxxers would post an entire résumé, expose a lifetime of scandals, then append a single “lol” as if that made it sport rather than bloodletting.

The shrugging guilt meme also marked the divergence between generations. Seniors—those who remembered a time when guilt required at least a stiff drink—were baffled. To them, “lol” was not absolution but mockery, proof that the young had no sense of gravity. The young, in turn, found their elders’ indignation quaint. What was the point of gravitas when the future itself was a punchline?

The phrase thus became the anthem of a cultural civil war: the Gen-Xers and Millennials muttering, “This isn’t funny,” the Zoomers and Alphas replying, “Am I a bad person? lol.” Both were correct, and both were doomed.

Footnotes

[7] A laminated food handler’s permit could be acquired in most U.S. states for $35 and two hours of online training. It remained valid employment currency well into the 2040s, unlike many degrees issued in the same decade.

[8] The 2029 Journal of Emergency Medicine documented a case in which a treatment protocol suggested by an AI was traced back to a Reddit thread titled, “I’m not a doctor, but here’s what worked for me.” The patient survived, though only after ignoring the emoji advice.

[9] For an exhaustive taxonomy of “lol,” see Tanaka, S. (2042). Irony as Immunity: The Semiotics of Shrugging Guilt in Early 21st-Century Digital Culture. Critics argue that the book’s inclusion of a 300-page appendix consisting solely of screenshots was either genius or madness.

VII. Case Studies in Collapse

While broad trends capture the sweep of the University Collapse, it is the case studies—the individual absurdities—that reveal its true flavor. The following episodes, drawn from archives, oral histories, and memes, demonstrate how collapse expressed itself not in grand narratives but in small humiliations.

1. The Great MBA Exodus

By 2029, MBAs were as common as houseplants and nearly as useful. Entire graduating classes found themselves funneling into laundromats, dog-walking apps, and mall kiosks. A meme circulated showing a line of freshly suited graduates at a Jamba Juice job fair under the caption: “Masters in Blending, Business or Smoothies?”

Economists described this as “malemployment,” though the public preferred “the MBApocalypse.”[10] The tragedy was not merely wasted tuition but the evaporation of managerial competence. Companies filled their ranks with MBAs who could model complex derivatives but could not unclog a supply chain.

2. The Iowa City Bunker

Conspiracy theories thrived during the Collapse, none more persistent than the tale of the Iowa City Bunker. Allegedly, provosts from shuttered universities retreated to a fortified underground facility where they continued to set global textbook prices by candlelight. No evidence has ever been produced, but the myth persists, reinforced by satirical TikToks showing hooded figures chanting “$399.99” in Gregorian tones.

The “Bunker Provosts” became a kind of boogeyman for the era, blamed for everything from student debt to cafeteria shortages. Ironically, the University of Iowa’s actual underground storage facility—used for rare books—was raided in 2030 by conspiracy tourists who left disappointed when they found only microfilm and climate control equipment.

3. Doctor of Philosophy, Assistant Manager of Chili’s

Few artifacts capture the absurdity of the era better than a single billboard outside Dallas, Texas, photographed in 2031. The sign announced with cheerful pride: “Meet Dr. Sandra K., Assistant Manager of Chili’s. Ask her about 18th-Century French Literature while you wait for your fajitas!”

Intended as a quirky marketing gimmick, the billboard went viral. Customers did indeed ask Dr. Sandra about French literature, and she obliged—sometimes with more enthusiasm than she showed explaining the margarita specials. Her resignation letter, preserved in digital archives, concludes: “Chili’s deserves a manager. I deserve an audience.”

The episode became a parable, cited by both sides of the debate: critics saw it as proof of higher education’s uselessness, while defenders saw it as evidence of squandered potential in a system that valued fajita upselling over intellectual contribution.

VIII. Conclusion: Collapse as Comedy and Tragedy

Looking back, it is tempting to view the University Collapse as inevitable. Costs were unsustainable, debts unpayable, and degrees increasingly ornamental. But inevitability does not preclude absurdity. What makes the Collapse uniquely memorable is not merely that it happened, but that it happened with laughter.

Students laughed at their useless degrees. Employers laughed as they pushed out seniors. Politicians laughed as they declared crises unfixable. The culture at large adopted laughter as both shield and sword. To live in the late 2020s was to oscillate between horror and hilarity, often in the same breath.

The phrase “Am I a bad person? lol,” unearthed from a private server during the Unspooling, encapsulates this duality. It was both confession and absolution, tragedy and farce. It revealed a people who knew exactly what they were doing, knew exactly how destructive it was, and chose to laugh anyway.

In that sense, the Collapse foreshadowed the Doxxing Wars. The wars were not born from malice alone but from irony weaponized. To expose, to ruin, to topple institutions—all could be done with the shrugging cadence of “lol.” The same shrug that excused useless degrees and untrained successors excused reputational assassinations.

Thus, the University Collapse must be remembered not simply as the implosion of an institution but as the cultural dress rehearsal for a conflict defined by tragic comedy. It was the barbecue before the funeral, the kegger before the coup.

As one satirical historian remarked in 2074: “If Rome burned while Nero fiddled, America burned while everyone shitposted. The difference is that Rome at least pretended to mourn.”[11]

Footnotes

[10] The Journal of Applied Economics (2030) defined “malemployment” as “employment grossly mismatched to formal training,” though the paper’s reviewers noted that the term sounded more like a digestive disorder than an economic condition.

[11] F.J. Morales, History as Meme: Irony and Empire in the 21st Century (2074). The book’s cover features the “This Is Fine” dog sipping coffee in front of the Colosseum.