Tomiko was already in the water when the trouble started.

The tank was supposed to be decorative, a shallow ring of goldfish and filtered light built into the top of the park’s big central pool. Kids pressed their faces to the glass. Parents read the rules about not tapping, not feeding, not wading.

Tomiko read the rules and stepped over them.

She kept her clothes on, climbed the rail, and dropped feetfirst into the pond. Cold slid under her shirt and wrapped her ribs. Somewhere above, someone shouted; the sound bent strangely as it crossed the surface and dissolved into the slow roar of pumps and hidden pipes.

Breathing stopped being a problem almost immediately. The first breath she didn’t take was the hardest. After that, her lungs just… opted out. No burn, no panic. Her body decided the rules of air no longer applied.

She opened her hand. Colored pencils drifted around her like small, polite spears. She caught one, a blue so bright it hurt, and started to draw on the white concrete walls of the tank.

Lines. Scales. Little sigils only she understood. A doorway that wasn’t there before, just a rectangle of color she filled and filled until it felt solid under her palm.

The goldfish didn’t mind. They nosed past her fingers, flashed orange and white in the corner of her eye, turned her vandalism into a moving mural.

Farther along the curve, on the smooth bottom, a goldfish lay on its side.

Its eye was open. Its mouth made no effort at all.

Tomiko closed her hand around it. The body was light and slack, the way a secret is once everyone already knows.

There was a tunnel mouth just below the painted doorway, a dark hole where the filtered water slipped out. It wasn’t big enough for a person, but it didn’t need to be. It was big enough for a body.

She slid the little fish into the current and let the pump take it. Down, away, into wherever the park sent things it didn’t want to deal with anymore.

She didn’t say a prayer. She just watched until the tail vanished.

Then she tucked the pencils back into her fist and swam up.

The tunnel she chose wasn’t the one the fish went down. It ran the other way: narrow, ribbed, pushing water against her shoulders. She pushed back. Her hair streamed behind her. The current tried to insist, and she insisted harder.

Somewhere in the middle of that climb the tank gave way to something else. The pipe widened into a long glass tube, thick as a subway tunnel. Beyond it was not concrete but an entire other tank, a huge enclosure full of slow green light and things that had teeth.

They came into view one by one, hanging in the water like questions that expected wrong answers.

The first had the thick, muscular body of a fish and the head of a snake. The hood flared when she reached toward it, a cobra’s halo opening and closing around a smooth, unreadable face. It didn’t strike. It just warned.

“Okay,” she told it in the muffled quiet, bubbles of words that went nowhere. “Point taken.”

Another joined it, then a third. Moving together, they were less like animals and more like a committee. She didn’t touch them again.

A smaller shape twitched at the edge of her vision. Bright orange, narrow as a knife, with a long black beak like a sword-tail, built backwards. It darted in and nipped at her calf. Sharp, not deep. An accusation with no follow-up.

She flicked it away with the back of her hand. It kept circling, looking for loose edges.

The tunnel kept going up.

Eventually the glass curved into a ceiling with sunlight dithering on it. Steps appeared underfoot—actual steps, tiled and wet—and without quite noticing the moment it happened, Tomiko went from swimming to walking. The water clung to her skin like an extra layer of thought and then slid away. Air rushed in. Her lungs remembered their job and took it back.

She broke the surface into noise.

Children ran past in swimsuits. Tourists shuffled on damp concrete. Somewhere behind her, pumps hummed. And in front of her, wearing khaki shorts and righteous indignation like a uniform, stood the park manager.

He looked like someone had ordered “Steve Irwin” from a catalog and gotten the deluxe package: safari hat, sunburnt nose, the whole thing.

“Mate,” he said, horrified and offended in equal measure, “you can’t just jump into my display. There were goldfish in there. One of them’s gone. Do you realize what you’ve done?”

Tomiko stood there dripping, pencils still clutched in one hand, and looked him in the eye.

“I drew on the walls,” she said.

“You killed my fish!”

“I found your fish dead,” she said. “Then I sent him downstream. I don’t do half-measures.”

He kept talking. Liability, property damage, emotional distress for the watching children. His words bounced off her like hail against glass.

Behind him, escalators rose in mirrored pairs, carrying people up to higher levels of the park. The air was thick with chlorine and popcorn oil and the faint electric tang of old machinery.

She turned away from him and stepped onto the nearest downward escalator.

As she stepped onto it, a teenage boy slid in beside her, dark skin, scabbed knees, eyes like sharp marbles.

“Are you a girl,” he asked, “or not?”

Tomiko didn’t turn her head. She raised her free hand and flipped him off, lazy and precise, and rode the moving stairs all the way down.

By the time she reached the lower level, the escalator next to hers was a mess. A whole crowd was trying to push down the up-side, jostling and swearing as the steps carried them stubbornly in the wrong direction. They weren’t trapped, exactly. They were just committed to fighting the machine instead of using the one that would take them where they wanted to go.

Tomiko walked past them. Her clothes were starting to dry at the edges, itchily. Her fingers smelled like pencil shavings and lake water.

At the bottom of the escalator, there was a long wading pool, maybe 3 feet deep – maybe less. The teenager found her again there, at the leading-end of it. He had a younger friend with him, who was bragging about his bathing suit, and she knew this wasn’t about his swimwear. Then, the teenager said to her, “I will build you a tool!” and she knew what he meant, and didn’t like it. She pushed past him and waded through the pool to the other side.

Down here, the tanks were different. More glass, more fish, more railings. But air everywhere. Water only in curated rectangles, where it could be supervised. Why were things different than on her trip up? On going back down, had she come the wrong way?

She wanted the first tank back. The one where the water touched the sky and nobody had yet told her she wasn’t allowed to breathe in it.

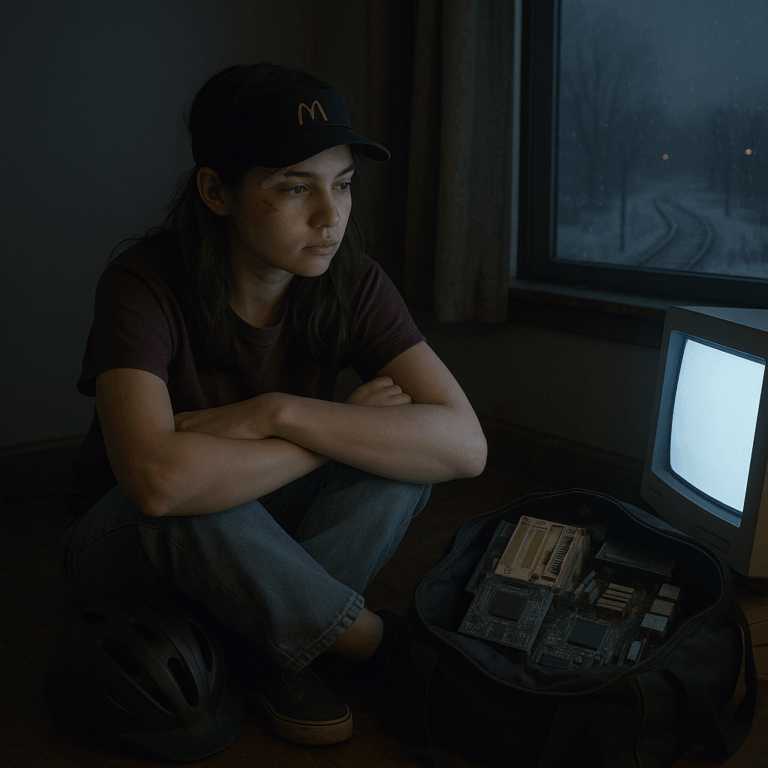

Instead she got a folding table and a plastic chair and a magistrate who looked like he’d been assembled from spare parts in a back office thirty years ago.

The CRT monitor on his desk glowed a tired grey-green. His tie was crooked. His expression wasn’t.

He looked her up and down, then down at the screen.

“All right,” he said. “So. You’re clearly a man, but you have a woman’s name, and you’ve been vandalizing park property and interfering with wildlife. The head keeper is furious. Why would you do something like that?”

Tomiko opened her mouth. Closed it again.

She could feel the water drying on her, turning every inch of skin into something that didn’t quite fit.

“I have a woman’s name,” she said finally. “The rest of that sentence is your problem.”

The magistrate’s smile was thin as printer paper. He tapped a key. The monitor beeped.

“You can make this very simple,” he said. “You say what we both know you are, we dock you for property damage, we let you go home. Or you keep pretending, and this turns into a very long afternoon.”

She thought of the dead goldfish sliding down the dark pipe. No trial. No cross-examination. Just current.

She thought of the cobra-fish flaring their hoods and not striking.

She thought of the little orange thing nipping at the soft parts.

She imagined, briefly, putting the magistrate through that tunnel as well, then let it pass.

“Maybe,” she said, “you don’t actually know what I am.”

He leaned back like he’d just caught her in a lie.

“It’s obvious,” he said.

It was not obvious to the woman standing behind her.

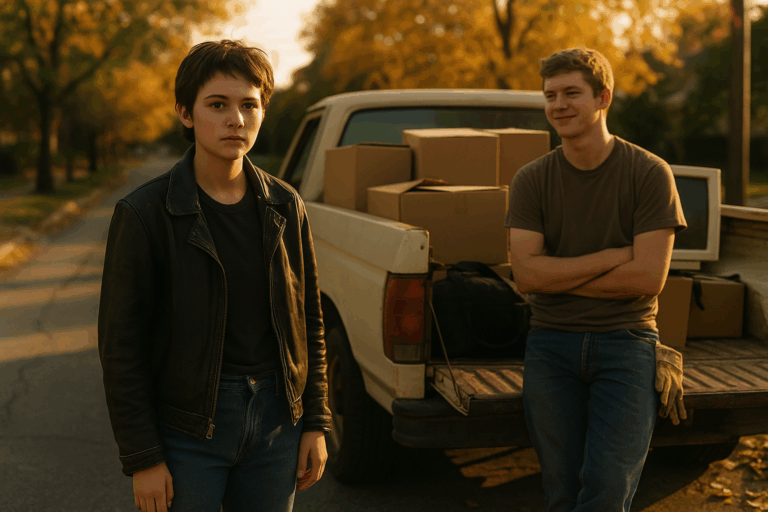

Vivian didn’t announce herself. One moment there was the stale, humming air of the tribunal room and Tomiko’s heartbeat in her ears; the next moment there was a hand on her shoulder, warm and firm, and a second spine aligning with hers.

“Hi,” Vivian said over Tomiko’s head, bright and pleasant. “Sorry, she’s not actually allowed to talk to you alone.”

The magistrate blinked. He hadn’t heard the door open. He looked past them as if he might find a second body and failed.

“And you are?” he demanded.

“The one posting bond,” Vivian said. “The other name on the account — her counsel. Pick whichever metaphor makes you feel more in control.”

Tomiko didn’t look at her, but she could feel the presence now—like the water coming back around her, only this time there was another swimmer in it.

“She’s already admitted to vandalism,” the magistrate said. “She defaced a tank and disposed of an animal without authorization. There will be consequences.”

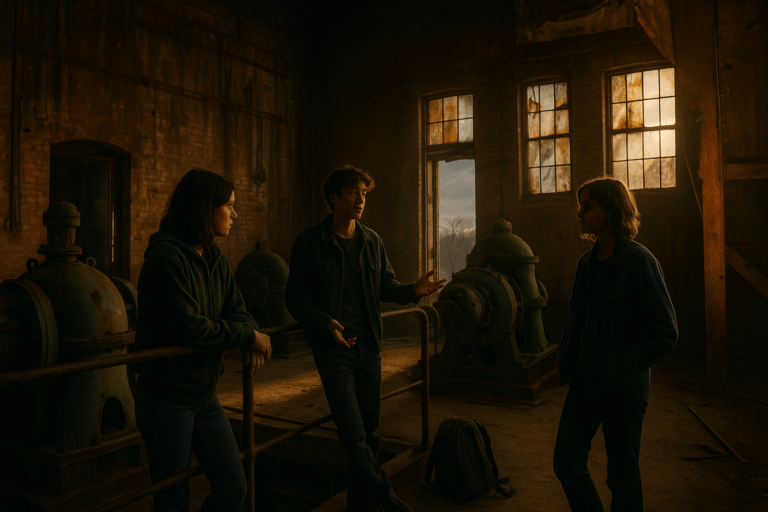

“She returned a dead fish to the system that killed it,” Vivian said. “Call it litter pickup. As for drawing on the walls, you’re welcome. Have you looked at this place?”

“You can’t just—”

“Also,” Vivian added, “that line you just tried about what she ‘clearly’ is? Don’t do that again.”

Her voice wasn’t louder. It just arrived differently. The old monitor flickered as if someone had pressed a magnet against the side.

“We’re not here to argue ontology,” the magistrate snapped. “We’re here to establish responsibility.”

“Responsibility,” Vivian said, “is that she saw a body and didn’t leave it there. Responsibility is that she knew your tunnels only run one direction, and she went up anyway. You want to charge someone with death, go find the engineer who thought a goldfish pond should share plumbing with whatever grinder you’ve got downstream.”

The magistrate’s face flushed. Rules gathered behind his eyes, ready to march out and do formation drills.

Tomiko turned her head, just enough to see Vivian out of the corner of her eye.

“You came back,” she said softly.

“I was never gone,” Vivian said. “You just turned the volume down so you could hear yourself think. Fair enough. Done now?”

Tomiko thought about the water again. The weightlessness. The quiet.

“Not really,” she said. “I was trying to get back there.”

“Then let’s stop arguing with the furniture and go.”

The magistrate slammed a hand on the desk.

“You are not dismissed,” he said. “You—”

Something under the table gave a little shudder.

The floor wasn’t quite level anymore. A thin film of water crept out from under the legs of the folding chair, cool around Tomiko’s ankles. It smelled like the first tank, not the chlorinated reek of the public pools. Pencil-shaving and lake and something old.

The magistrate looked down, startled.

“What the—”

Tomiko didn’t wait.

She stepped sideways, off the patch of dry tile and into the thin spread of water, and it took her like it had been waiting. One breath, two, and then the floor wasn’t there. The room wasn’t there. The monitor’s glow stretched and snapped.

For a second she was somewhere in between, pressure in her ears, Vivian’s hand still anchored to her shoulder.

Then they were both under.

Same tank, same pale concrete walls. Same goldfish, looping their dumb, easy circles like nothing had ever happened. Her drawings were still there, too, bright and defiant on the white—doorways and sigils and a tunnel mouth that knew her hand.

Vivian was beside her, hair floating out like white weed. She was not a ghost or a reflection. She was as solid as Tomiko, as present, as held by the water.

Tomiko waited for panic. No air. No surface.

Nothing came.

“See?” Vivian’s voice arrived like touch, not sound. “Not all that bad.”

Tomiko flexed her fingers. The dead fish was gone, far past caring. The tank was just a tank again. Above them, the distorted shapes of park guests drifted by, fenced off by glass and their own assumptions.

“Can we leave?” Tomiko thought back at her. “If we want?”

Vivian nodded toward the painted tunnel.

“Pick a direction. Up, down. We’re not bound to their plumbing. That’s their dream.”

“And if Steve Irwin’s waiting?”

“Then he can yell at a fishtank,” Vivian said. “We’ve got better things to do.”

They swam.

Not because they were being chased, not because a court demanded it, but because there was more water than this and they wanted to see where it connected. The tunnel admitted them like old friends. The current tugged. They let it, a little.

Somewhere behind them, in a room that might already be flooding without realizing it, a magistrate shouted at an empty chair and a flickering screen.

Somewhere ahead, there would be other tanks, other pipes, maybe even open sea. Places where “underwater” didn’t mean absence but choice.

When they wanted air, they would surface.

When they wanted quiet, they would sink.

The charge never stuck. The guilt washed off. The name stayed.