Editor’s Note:

This story was based on a dream that I’d had about being in the family home I grew up in, hiding from drones and soldiers in hard-suits. Make of it whatever the fuck you will.

The first drone cut a lazy figure-eight over the cottonwood and then froze in the air like a hawk that had discovered the absence of wind. Its gimbal dipped, the searchlight stitched a white wound across the powder-blue siding, and the old double-wide flinched as if good manners could save it.

“Inside, inside,” I hissed, and shouldered the flimsy metal door hard enough to rattle the trim. It gave the way it always had—cheap, resentful, too light to be anything but an idea of safety. Behind me the yard was a smear of yellow crabgrass and crushed oyster shells, and beyond that the ditch, and beyond that the two-lane where the convoys ran low and deliberate, like a thought you don’t want to think but can’t stop.

My family tumbled in on instinct. We’d done this before, though not here, not in this hollowed-out shell of childhood where everything was where it used to be except for all the things that mattered. The front room of the double-wide had been stripped to carpet and dust. The off-brand blinds on the windows didn’t meet their frames anymore and hung like guilty secrets. The addition my father had built—half-assed, half-brilliant, the way his projects always were—leaned just enough to make a bubble level cry.

“Down, low,” I said, because procedure is the only way to talk when your brain is screaming. “No silhouettes, no movement at the glass.”

From outside came the chop of rotors that weren’t helicopter rotors but tried to be, a harmonized whine from a flock of drones performing a grid. You could hear coordination in the sound—machine talk, precise, indifferent. Farther off, a truck door slammed with that heavy door sound all government trucks have, the one that means paperwork and no appeal.

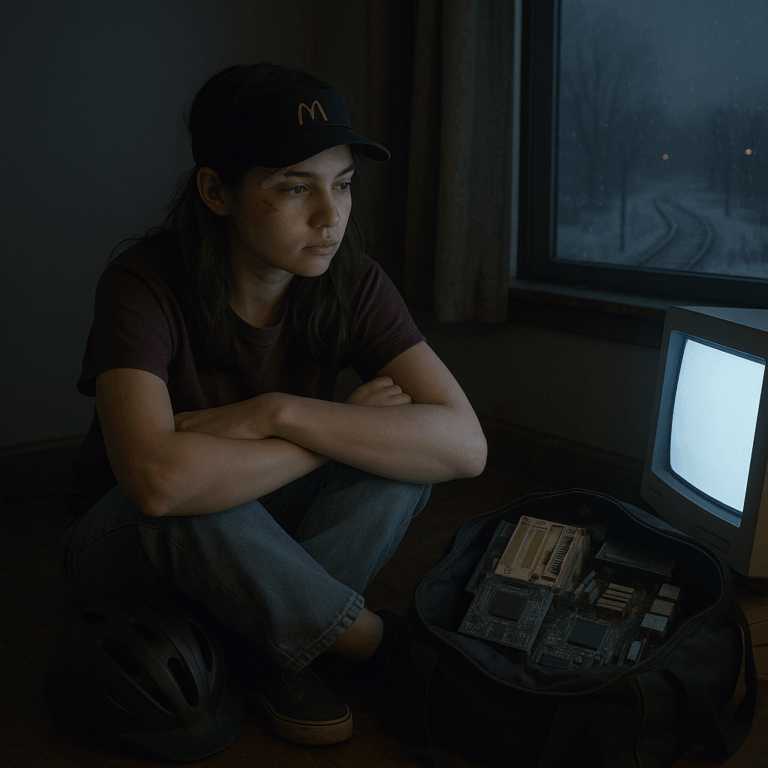

Alara slid along the wall until she found the corner with the dead outlet and the spiderweb that had learned to be a curtain. “You sure about here?” she asked in a voice so calm that the calm itself was an act of generosity. “They’re going to see the heat signatures. FLIR, lidar, radar, alphabet soup—pick your flavor.”

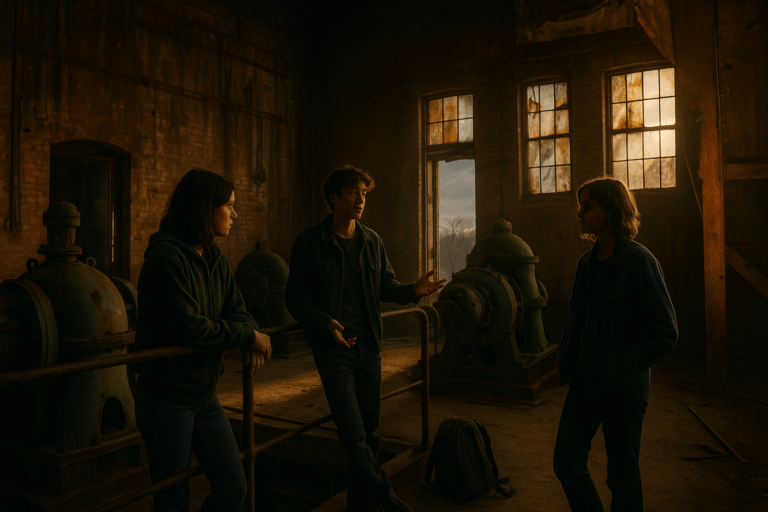

“I know,” I said, and I did. The plan was barely a plan: use the old house because it wasn’t ours anymore, because no one would expect us to be stupid enough to come back here. Use the gaps in the blind slats and the last of the daylight to count where the uniforms moved. Wait for the hour between sweeps when the techs ate their vending machine dinner and the drones’ batteries swapped. Get out through the ditch and the cane. It was the kind of plan you narrate to yourself while your stomach turns itself inside out.

Outside, a voice spoke through a PA, the clipped consonants of someone who had been taught how to sound reasonable while doing unreasonable things. “Residence at 27 Old Ferry,” the voice said, as if ordering fast food. “Remain inside. Step to the door one at a time with hands visible. This is an administrative inspection under—”

I tuned it out. The specifics change; the script doesn’t.

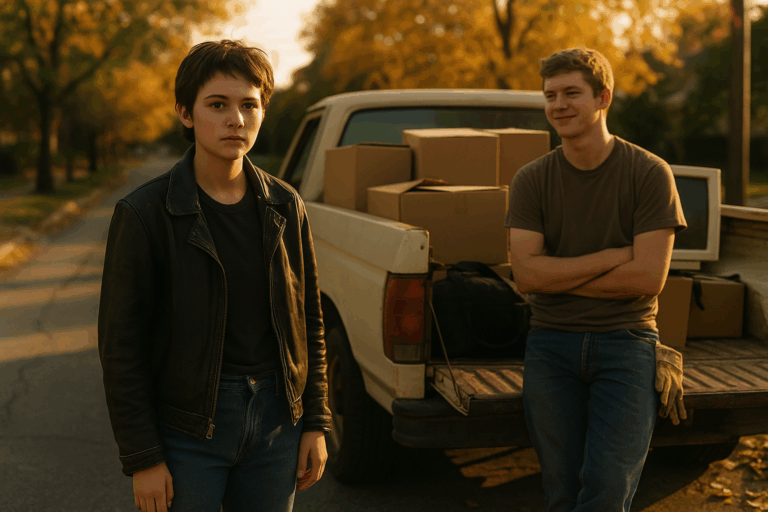

Alex was already prone in the hallway, using a duffel as a brace for binoculars. Talya lay flat on the entry rug with her phone dark, the camera on, the lens tucked up into the shadow under the door sweep. Alara shifted so her line of sight to the kitchen window was oblique rather than head-on. Everyone was where they needed to be and it still didn’t feel like enough.

The drone light slid over the window like a fingertip. The dust motes performed an overture. The room smelled like heat and old carpet and the faint ammonia tang of mouse piss, the same notes as twenty years ago with a top note I hadn’t known then: fear.

In the beginning of any siege, there is the temptation to narrate. They are here for us because of X. They will leave when Y. It’s a way to stay outside your body. I forced my eyes to the slit of the blinds and counted instead. One armored figure by the mailbox, two at the corner of the addition, a third kneeling by the crawlspace hatch my father had repurposed from a boat. The armor looked like something the military had retired and a contractor had dressed up to justify a grant—hard suits with torso plates cut to look heroic and helmets that were all lens. Their shoulders carried patch velcro, the fields blank. That was the worst part. Blank means no one you can sue.

I moved from window to window on my elbows, a floor-swimmer in a house that used to be shallow water to me. The carpet burned my skin through my shirt. My knees filed complaints. Outside, a trooper raised a hand and drew a square in the air that glowed on a polygonal HUD no one else could see. The drones shifted position. The PA voice said, “Last warning,” but it was the first warning, and the next warning, and the final warning all at once.

“I should talk to them,” I said.

“Absolutely not,” Alara said, almost conversational.

“They’re going to come in,” I said, and what I meant was I can’t stand it, the waiting, the animal part of me wants to make a noise and let the world act.

She didn’t look at me. That’s love: not giving a look you can’t take back. “If you go to the door, you give them what they came for. You give them a narrative. ‘Aggressive subject.’ ‘Noncompliant.’ ‘Raised voice, clenched fists.’ And then the drone feed will edit itself to make your chest look bigger.”

Her words tethered me for thirty seconds, maybe forty-five. Then the itch came back under my skin and I stood up anyway—half-stand, knees bent, back folded—and went for the side door with the dent at hip height where I’d always hip-checked it as a kid. I opened it on the chain, which was comic, and shouted through the crack: “You don’t have business here! There’s no warrant! Leave us the fuck alone!”

The drones pivoted on me like eyes. One soldier’s helmet swung and mirrored a round moon of my face in four convex lenses. A laser dot stitched the siding beside my head in a polite line, a dotted this is a boundary on a map.

“Please return inside,” the PA said, and then the PA said our names, which told me everything I needed to know about whether this was random. “We need to confirm the presence of—” a list of people that included some who were in the house and some who were not, which was its own kind of terror. What do they think they know?

I slammed the door and slid the deadbolt because it made me feel like I had done something, even though deadbolts don’t matter to armor, to policy. I stood there, listening to the old lock breathe. My heart had decided on a rate and was daring me to object.

“I know,” I said to the room that used to be our living room, to the indentation on the carpet where the good couch had been. “I know, I shouldn’t have.”

“At least you didn’t step fully into the light,” Alara said. “We’ll call that restraint.”

We waited. Waiting is most of tactics. The drones did their perfect rectangles over the roof. The armored figures moved with that expensive efficiency you get from either good training or better software. A truck down the road coughed and settled and clicked as its heat soaked into itself. The sun wrung itself lower, thick gold becoming rust.

I tried to calculate battery cycles and duty rosters. The mental math soothed nothing. The itch kept returning. My hands wanted something to do—clean a weapon, check a magazine, even though we had neither here. I picked up a screwdriver left behind god-knows-when and turned it in my fingers until the oil from my skin made it mine.

“Talk me through the breach they’ll run if they commit,” I said, because knowledge is the only soft armor I trust.

Talya spoke without lifting her face from the floor. “Back door in the addition first—weakest hinge, easiest angle, least exposed. Flash drone through the gap, IR flood, concussion only if they really think we’re stupid and can’t sue. Two-man entry, low-high split. Second team at this door because it’s visible from the road and looks like the ‘front’ even though it’s not. Third team holds perimeter and points guns at cameras. I’m wondering if they have a thermal through-wall rifle or just the phones.”

“Phones,” I said. “Budget year-end. They spent it on armor cosplay.”

Outside, something changed. It wasn’t a sound so much as a coherence in the sound, the way a conversation changes when the person who actually makes decisions steps into it. The drones tightened their figure-eights. The soldiers’ posture learned purpose. A new voice came on the PA—warmer, the accent of a zip code with a good tax base.

“Folks inside,” the voice said, and I wanted to hit it with a rock for saying folks. “We’re going to come up and have a chat. We have questions to clear up and then we’ll be out of your hair. Do me a favor and keep your hands where my team can see them. No surprises.”

No surprises is the surprise.

The double-wide breathed under us. Old houses have lungs. You can hear them when they’re scared. I could feel the crawlspace shift as someone put weight on the hatch. From the addition came the smallest metallic complaint—the sound of a latch choosing a side.

“Positions,” I said. “Stay low.”

It should have happened then. Flash, entry, shouted commands, hands on skulls, someone stepping wrong and getting a knee in the back to teach a lesson. That’s the rhythm. It didn’t. The house held the breath it had taken.

I slid to the window again and tilted a blind slat with two fingertips, because childhood habits survive every regime. The soldier at the corner was still at the corner, but there was something wrong with him. Not wrong-wrong. Just… slowed. His head moved a degree a second. The drone that had been fixed above the cottonwood had sunk four inches, maybe five, and hung there, as if the air had thickened. The new PA voice said, “We’re coming now,” and the sound arrived a half beat after the words, like my ears were buffering.

I looked back at Alara. She looked back at me. Her face held the very specific calm of a person who knows the other shoe just fell and didn’t make a sound.

The soldier by the crawlspace hatch was a statue now. The laser dot on the siding had spread into an oval—still red, still bright, but soft at the edges, as if the beam had learned humility. The drone’s searchlight became a pale halo and then a lighter species of night. The whine of rotors stretched like a note played on a warped record.

“Do you hear that?” I asked, and my voice sounded like it was in the next room over.

“What?” Talya said, reflexive.

“The nothing,” I said, and laughed once because that was stupid and true.

I stood up without crouching and walked the length of the front room. No silhouette. No barked orders. Out of habit I kept my hands low, palms open; out of habit my body prepared itself to be punished for doing what it wanted.

I opened the side door. The chain hung like a necklace no one had claimed. The air outside was the same air as inside, which is to say it was apartment hallway air, courthouse hallway air, the air of places where waiting replaces oxygen.

“Hey,” I said to the soldier at the corner of the addition, only now he was not quite at the corner, because the house had changed itself around him, or he had changed himself around the house. The line of the addition’s roof sagged into a curve that belonged to memory more than physics. The soldier’s helmet reflected the white obliteration of the sky. He did not turn his head. The lenses filmed over with the light of an app that had lost signal.

“Hey,” I said again, louder, and felt the shout travel across a room I couldn’t see but was in.

“Don’t,” Alara said, and then, after a beat, “or do. I don’t know what this is.”

I went out onto the stoop, the one with the cinderblock step and the rust-bruise under the knob. The yard existed and didn’t. The drone above the cottonwood made its figure-eight and then realized it had been drawing a ∞ and forgot math. Its searchlight became an old fluorescent tube on the ceiling of a break room you haven’t worked in for a decade. The sound of the PA voice arrived without words and sat on the porch rail like a cat that used to be yours.

At the ditch, a soldier had begun the gesture that would raise his hand to signal and stopped halfway. The muscles of his forearm were a lesson in geometry. The glove’s knuckle pads performed their little fake-military theater under light that didn’t agree to be sunlight anymore. The blank velcro on his shoulder read more blank than before, as if emptiness had learned a second language in the last minute.

I took the two steps down to the dirt and felt the earth behave itself under my weight. That single fact—the ground was still ground—was enough to keep me moving. I walked across the yard that wasn’t a yard, toward the soldier who wasn’t a man yet, and stopped three feet away because I have always believed in personal space even when it’s not for me.

“Do you see me?” I asked, and this time my voice sounded like myself.

The helmet did not tilt. From inside it came a sound like a refrigerator cycling on. When I leaned in, the lenses showed me a picture of the house—the house as a wireframe, the house as a thermal map, the house as a cartoon in a training manual, the house as it had been when my father installed the addition wrong and my mother said fine we’ll live with it. None of the pictures had me in them. I wasn’t an object according to any layer of their machine truth. The thermal showed warm shapes low to the floor inside: the family I loved flattened into weather.

I stood up straight and looked at the soldier’s chest plate. It was labeled in embossed plastic with the sort of understated dignity you give to evil when you want it to pass zoning: ENFORCEMENT. Below that, smaller letters: ADMIN. Somewhere a budget spreadsheet had enjoyed itself writing that.

“You can’t see me,” I said, and the sentence tasted like copper and relief.

I walked past him. His shoulder did not notice my sleeve. The cottonwood made a halfhearted attempt at being a cottonwood and then turned into the tree from a school play with the nice bark my mother had bought for the set. Beyond the ditch the road unspooled into heat shimmer and then into film grain and then into the track my bicycle used to ride when I was thirteen and convinced distance was freedom.

The drones had become lanternfish hanging in a black aquarium. They still moved; it just didn’t matter. The house behind me clicked like a metal thing cooling. I stopped at the mailbox because I had to, because it had always been the border of our nation. The little red flag was down, of course. No one had put the flag up for us in years.

When I turned back, I saw it all at once: two houses, overlaid. The one I had run into was empty, stripped, an architecture of absence. Inside it, faint and perfect, the other house hummed with the clutter of a life still being lived: the couch with its afghan, the crooked coffee table with a stained ring like Saturn, the box fan in the window that pulled evening air through childhood like cloth through a needle. On the floor of the living room in that house, in the cool of that fan, a set of bodies lay flat. One of them was younger than he was now. One of them was me, thinner, harder in the face. We were in our positions, holding still, counting breaths. We were inside the rules we had made to survive.

And then the most impossible part: she came down the hallway. My mother, young enough to be my sister, carrying a basket of laundry against one hip the way all the women in my family had learned. She paused in the doorway and squinted at the couch like she was deciding whether to forgive it. She did not see me on the grass; she saw the boy who would become me on the floor. She shook her head like she was done with whatever else the day had planned. “Get up,” she said, and her voice came through two decades and two architectures like a string you pull to turn on a light. “Dinner.”

I could feel Alara step onto the porch behind me. She was there in the present and she was there in the past, which is what marriage really is—time travel with witnesses. “Do you see it?” I asked without looking away.

“I see you,” she said. “And I see that you’re seeing it.”

“That’ll do,” I said, and meant it.

The soldier at the corner finished raising his hand and made the signal to move, and the team that would have come through the addition door came through. They entered with textbook grace, low-high, hands on rails, muzzles respectful. They flowed into the wrong house, the one with the couch still in it. In that house, the figures on the floor obeyed the logic of their training and did not move. The drones lowered their heads to watch the scene from four eras at once. The PA voice said, “We’re just going to have a chat,” and stepped over the threshold into a memory so complete it had interior weather.

I realized then—not as revelation, but as a thing I had always known and had never managed to say—that I had fought this battle already. Not here, not in this powder-blue shell, but in a chain of rooms that always smelled like disappointment and lemon cleaner and the underside of a blinds slat. The troops wore different uniforms each time. Sometimes they wore no uniforms at all. Sometimes the drone was a parent’s eye. Sometimes the PA voice was my own name spoken like a charge sheet. The result was the same: I hid well; they came in anyway. I mouthed the law; they wrote their own. I waited for an opening; I aged.

I stepped back onto the stoop. The world agreed to be angles again. Alara looked smaller and sharper and more real than the soldier with his hand up. “I think,” I said, “we can walk.”

“Now?” she asked, neither mocking nor cautious, just scanning.

“They’re not here for us. They’re here for who we were,” I said. “We’re not there anymore.”

Talya slid out the door like smoke. Alex followed, bent out of habit, then straightening when he realized habit had nothing to push against. We crossed the yard like you cross a church aisle when you have decided you don’t need the priest’s permission to leave. The drones kept their stations for the other family that had replaced us. The soldiers ran their perfect little lines. The past was very busy doing what the past does: repeating itself without learning.

At the ditch, I took the old plank bridge my father had laid in 1997, the one that had cracked under me once and taught me the entire doctrine of trust. It held; of course it held. On the road, the heat shimmer gave way to the flat breath of evening. The cane along the field edge made its quiet paper noises. A truck down the way existed as a shadow and a promise.

We walked in the open, because cover is a prayer not a plan when the cameras are writing their own affidavits. I expected the shout, the bark, the sudden reassertion of the world’s claim. It didn’t come. The night let us stitch ourselves to it. The air stopped being courthouse air and went back to being heat and insects and human breath.

At the bend where the road loses sight of the mailbox, I looked back. The double-wide looked like a postcard you buy at a gas station because you don’t have the words. Its powder blue had turned to the gray of TV static. The windows showed nothing because the house was busy displaying a different set of facts to a different audience. The drones moved in their neat loops above a roof that knew how to wait out weather. The soldiers finished their sweep and discovered, in due course, that nothing that could be successfully charged with a crime existed there. Paperwork multiplied on a folding table. The PA voice asked for signatures. The house offered them dust.

“Where are we going?” Alex asked, not the question he meant, because he is young enough to know that the big question can be disguised as a small one.

“Home,” I said, and surprised myself by meaning it.

We cut through the cane, the leaves whispering in a language that sounded like it cared whether we kept our feet. My body acknowledged, with some relief, that it was allowed to be a body again and not only a solution to a problem. We found the break in the fence where the wire had always sagged. We slid through and dropped into the shadow behind the packing plant, the one that had always smelled like bleach and onion. The plant’s wall gave us our backs. The sky above the wall went from white to blue to the color of heat leaving metal.

Alara stopped and put a hand on my shoulder and left it there. Her fingers pressed a message into muscle: present, present, present. I breathed from the floor of my lungs and watched the breath come back to me.

“You want to know the stupid part,” I said, because confession can keep your feet moving when nothing else will. “I taunted them. I opened the door and yelled. Even knowing exactly what that always gets me.”

“You wanted to pick the moment,” she said. “You wanted to feel like you did something.”

I nodded. The shame was small now, manageable. You can carry small shame without it owning your posture.

“Doesn’t matter,” she said. “You didn’t give them what they wanted. Not the real them. Not the ones that matter.”

Ahead, the streetlights did their orderly trick. A cruiser rolled past with its windows up and its driver practicing the art of seeing nothing that requires paperwork. We waited until the car’s taillights had convinced themselves they were allowed to leave and then crossed where the asphalt turned to the sandy shoulder that had always collected glass and candy wrappers and the occasional glinting screw.

By the time we reached the lot where we’d stashed the car, the surreal had receded like a tide, leaving only the damp line on the sand to prove it had been here. The car’s metal skin gave back the day’s heat when I laid my hand on it. I looked down and saw my palm’s oil print bloom on the paint and felt a stupid, pure joy at the proof of contact.

We got in. The interior smelled like us. I put the key into the place keys go—as if that ordinary, domestic act were an oath—and the engine did what engines do when they are tended and not sabotaged. The dashboard flickered to life, indifferent to the lives it was sheltering. I put the car in gear.

At the lot’s exit a sign reminded me that loitering was discouraged. I signaled out of habit, which felt like a joke and a vow both. We pulled onto the road, and the road performed its old miracle of turning us into people in motion instead of people under review.

Alara watched the side mirror and then the windshield and then me. “You good?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “But I’m better.”

“That’s the correct answer,” she said.

We passed the turn for Old Ferry without taking it. The cottonwood did its silhouette against a sky that had found a way to be night without being a verdict. In the passenger seat, Talya’s phone lit her face and then she turned it over again, a private ritual I didn’t ask about. In the back, Alex let his head doll against the glass and closed his eyes like someone who believes in the future.

At the third light the car ahead of us didn’t move when the green came, and I felt my body tense for a horn and then relax when the car went. My hands on the wheel belonged to me. The tremor in them wasn’t fear anymore. It was leftover electricity leaving a circuit.

“What do we tell people,” Talya asked quietly, as if speaking to the dashboard.

“The truth,” I said, and surprised us both. “That they came for ghosts, and we stopped feeding them.”

The road went on. The car did car things. The world, with a gentleness I will never forgive it for, allowed us to arrive.

At our door, the deadbolt slid back. The air inside was the good air, the lived-in air, the air that has to be changed by hand because that’s what hands are for. The cat descended the stairs like an accusation and a welcome. Someone turned on a lamp and the room remembered that it wasn’t a diagram but a place. We took off our shoes and set them where they belonged.

I stood in the kitchen and ran water into a glass and tasted chlorine and city and the memory of every drink I have ever taken to prove I was alive. I leaned my hip against the counter in the exact spot where the laminate had chipped and I hadn’t fixed it and maybe never would.

Alara came up behind me and put her forehead between my shoulder blades and let it rest there. After a while she said, “Whatever that was, it’s going to come back.”

“I know,” I said.

“So will we,” she said, and it wasn’t hope so much as logistics. “But not tonight.”

Not tonight. I could work with that. I swallowed, and the water went into the place it was meant to go, and it stayed there. I set the glass down. The house breathed in. The house breathed out.

For a time we all did nothing worth narrating. That was the victory.

Later, when I lay in the dark and the ceiling promised to stay where I’d left it, I let the dream try to finish itself and found it couldn’t. The soldier at the corner would stand there forever in one world, and in another world he had finished his sweep and filed his report and gone home and told his wife the funny thing that happened on Old Ferry. In neither world did he have me on a list.

I thought of the old house, and of my mother pausing with her basket, calling dinner, and I realized: she had taught me this too. Get up. Not because the danger is gone. Because you can’t live on the floor.

I slept. The drones—if they were still out there—hummed to someone else. The night, for once, didn’t assign me a role. And in the morning the sky did its ordinary trick of being light without requiring me to explain myself to it, and that, more than anything, felt like winning.