Editor’s Forward:

Here’s another story that comes from a dream I had a long time ago. In this case, Callie and I decided to push the absolute limits of AI and human collaboration, so we set out to write a 10,000 word whopper of a story.

I have to tell you that I was absolutely rolling with laughter reading this. It is one part It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, and one part Cory Doctorow’s Someone Comes to Town… and it never stops for a second to apologize for itself.

Have fun with it. If you’ve ever lived in an old house, you’ll probably find something here that resonates with you. If not, count your blessings – and the number of wires that you know aren’t up to code.

By the time the man everyone called Danny DeVito handed them the keys, the house had already made three separate attempts to kill them.

First was when the front step flipped like a sprung jaw as they set a foot on it, a seesaw of rotten 2×8 pivoting on a rusted gutter spike. Second was the foyer light that came on when they tried the doorbell—two seconds of cheerful glow followed by a sound like a lit cigarette dropped into a bird’s nest, then a puff of blue from behind the beveled glass. Third was the thermostat that read 74 in January while their breath made steam, a small act of performance art in a home that had the original sin of knob-and-tube and the grafted-on sins of a hundred “improvements” by men who believed wire nuts were optional if you prayed.

“Don’t step there,” Danny said, as if it mattered, pointing to a stretch of living room that was more bow than floor. “Or there. Or under that. That’s the wine cellar.” He said wine cellar the way other people said “sinkhole.”

They looked down. There was no hatch, no staircase: just a rectangle of plywood laid like a bandaid over a square of softer plywood. “The wine cellar,” they repeated, because naming is a way to survive.

“It’s more of a spiritual category,” Danny said. “You get the keys or you gonna keep narrating your life?”

They’d met him three months earlier at closing, in a conference room that smelled faintly of toner and old men who would rather be golfing. He’d worn a suit that might have belonged to a more successful uncle and a smile like he’d just remembered a joke he’d never tell. He’d bought the place in ’96 and “improved” it ever since, which turned out to mean sheetrock over plaster, carpet over tile over carpet, and an ambitious relationship with conduit. His wife had left him for a man with straighter walls. He’d let the place harden around him like a shell.

Now he was selling because the city had a file on him you could wedge a piano under. There were red tags stapled to the kitchen window frame like angry valentines. His lawyer had told him, gently, that the next red tag would be nailed to the front door with a sheriff under it. So he’d found a buyer who could afford to be fearless: a person with a toolbox, a tolerance, and a past that made the present look manageable by comparison.

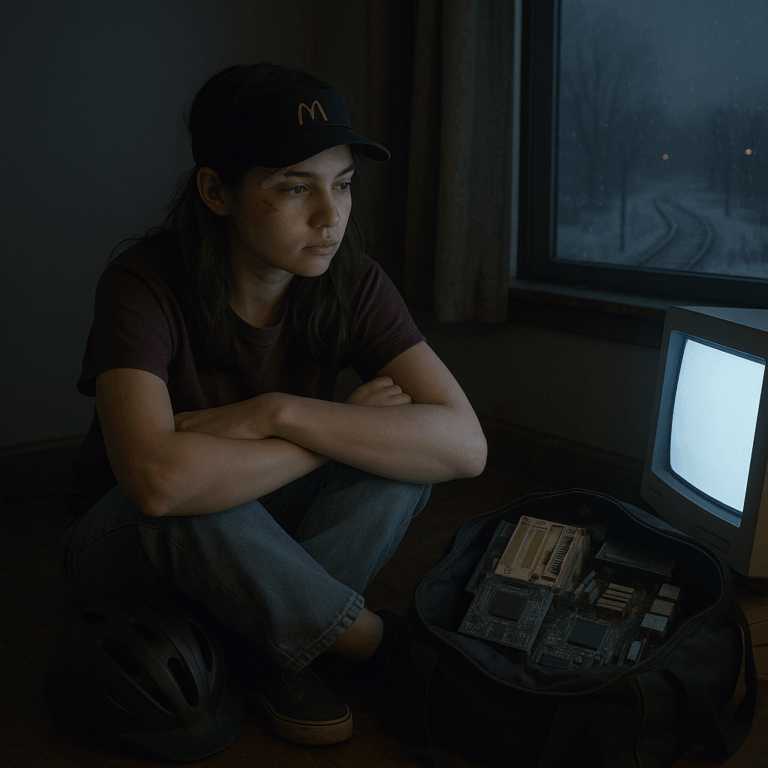

They were called Wren to the DMV and Ren to anyone who knew them. They’d spent a decade as a technician at a place that made magical thinking for money and a previous decade living on the wrong floors of other people’s buildings. Houses didn’t scare them. Owners did.

Danny dangled the keys. “You got someone to help you move?” he asked in a tone that said he’d decided they didn’t. “You got a church?”

“I’ve got neighbors,” Ren said, which would prove to be both true and the problem.

Danny’s mouth did a little purse, somewhere between sympathy and shame. He’d become the kind of man who believed neighbors were the opposite of church.

He dropped the keys into Ren’s hand. “Well, it’s your problem now,” he said with the airy cruelty of people who have found a new shore. “Congratulations,” he added, because he meant it. Even a haunted house is better than a storage unit.

The front door stuck; the house sighed; the heat, which wasn’t heat, breathed. Ren stepped over the booby-trapped plank, skirted the “wine cellar,” lifted the rag rug laid over a square bulge. Below the rug a cold air return yawned, its grille gummed with duct tape and paint. There was a spoon vanished into that paint mid-stir, fossilized in gloss. You could tell something about a man by the objects he lost in his house.

“Why is the thermostat lying?” Ren asked.

Danny shrugged. “It’s aspirational.”

The radiators, old hunched things with the elegant ribs of an extinct animal, were stone cold. Somewhere a blower ran like a distant airplane. The register vents breathed air that was warmer than outside and colder than any reasonable human life.

“It’s the heat pump,” Danny said. “State-of-the-art. You just gotta sweet-talk it sometimes.”

“How do you sweet-talk it?”

“You stand in the yard and beg.” He said it with enough sincerity that Ren had to believe he’d tried it.

They didn’t say much at the handoff. Danny walked them around the perimeter, pointing out features as if he were selling it again: the pergola that leaned like a drunk towards the neighbor’s fence, the shed with a door from three different bedrooms nailed into one, the concrete pad where an air-handling unit squatted like a patient dog. There was a sign half-buried in ivy that read OPEN in neon cursive. It leaned face-in to the fence like a shameful secret.

“What’s that?”

“Art,” Danny said blandly, then wouldn’t say anything else. It wasn’t attached to anything. It hummed anyway, faintly, like a mosquito you weren’t sure you’d heard.

—

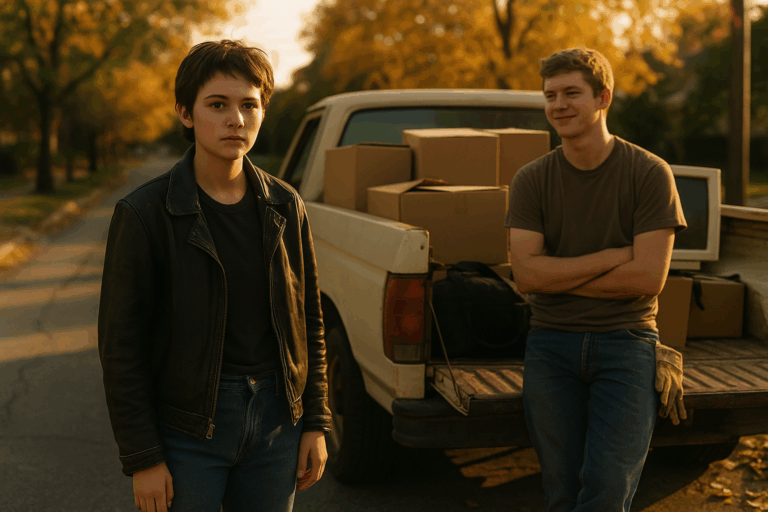

Ren moved their life in through the side door because the front needed a ritual and they didn’t feel ready. The side door stuck just enough to make it personal. They dragged furniture over thresholds, cursing in the low local dialect of men who have trained themselves not to wake babies. A neighbor—middle-aged white guy, sturdy as a nail keg, early retired or between gigs—appeared to grab the heavy end of the sofa without being asked. “Ed,” he said, and offered his hand like a loan without interest. “You the new one?”

Ren nodded. The name loosened something in Ed. “Well, thank Christ,” he said. “We been living in a haunted Home Depot. You planning to fix any of this?”

“I’m planning to try.”

“That’s the spirit,” Ed said, as if there were only two choices: planning to try and planning to walk away.

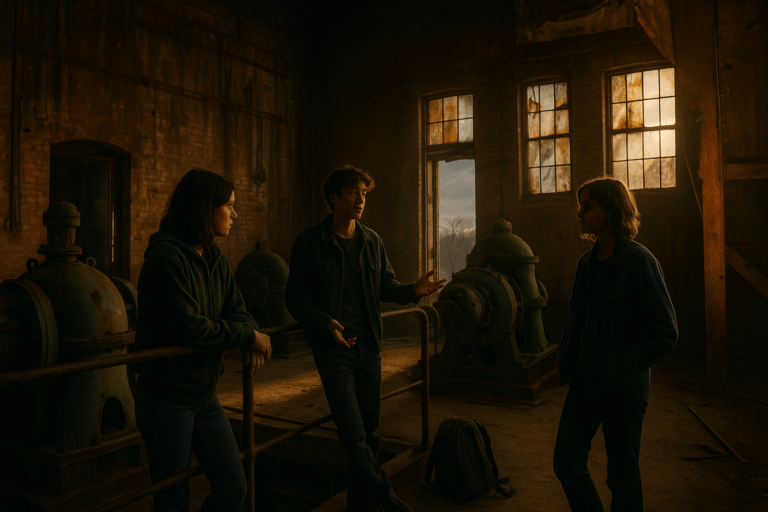

By noon two more neighbors had materialized: Miz Geneva from the end of the block, heavyset, black, a headwrap that meant business; and a wiry man with a face like a pocketknife who introduced himself as Saul “like the road but with more potholes.” They brought moving straps and common sense. Geneva brought questions.

“You an ally?” she asked within fifteen minutes, somewhere between a welcome and a test.

“In general,” Ren said carefully.

“That sign,” she said. “That—light.” She aimed her chin at the ivy. “That thing lights up the whole damn night. You know about that?”

“I just saw it for the first time. It’s not connected.”

“It’s connected to hell,” Geneva said. “You gonna fix it?”

“I’ll try,” Ren said, because that is what people like Ren say when they mean “I have no idea how yet,” and because in a neighborhood like theirs, There’s a plan almost always means There will be a plan.

Saul pried at a baseboard with a painter’s knife and made a face that meant mouse droppings. “Place has bones,” he said, which was both euphemism and truth. “I like a house that argues back.”

That first day was measured in what they learned to avoid. Ren marked soft spots with painter’s tape and wrote NO like a curse. They pinged outlets with a non-contact voltage tester and found live ones singing in the wrong key. They opened a bathroom vanity and discovered a family of wasps had made a paper city and died in it. They took down a mirror and found another mirror taped behind it, as if the wall had been taught to look back at itself.

At dusk the house did that thing old houses do: it shifted in the cold. A thousand boards moved by the thickness of a fingernail and the whole structure spoke nonsense. Ren stood in the dark kitchen and listened to it tell the truth in a language you only learn by living in it.

Then, after midnight, the humming grew louder.

They woke because the noise in their dream came from their waking life. At first they thought it was the heat pump’s distant bravery becoming a yell. Then they realized it had a pitch. It had moral certainty. Faint at first, like a fluorescent dying in a 7-Eleven, then brighter until they could feel it in their fillings. The house seemed to be lit from inside its walls, an indecent glow. The ivy at the fence had become a backlit innocence.

Ren slid a jacket over their shoulders and stepped onto the back stoop in their socks. January had done what January does: there was a skin of crunch over the grass and the air had that clean non-scent you could snort like a drug. The humming came from the fence line.

They stood there a minute because it’s important, when confronting the uncanny, to let it show you how it wants to be seen. The ivy breathed. The sign behind it—OPEN—was on. It had no plug. It glowed like a wound. Not LED, either; neon, the old voltage that sang even when it shouldn’t. The cursive was backwards, meant to be read from the street. Even reversed, your brain wanted to accept it. O-P-E-N, haloed, humming, the kind of light that calls every moth within a thousand miles to throw its body at a promise.

Ren took a step forward. The fence snagged their jeans. The air tasted like copper.

They didn’t touch the sign. You don’t touch the first day of anything.

In the morning, Geneva knocked with all the polite force of a building inspector. She stood on the stoop like a plaintiff. “See it?”

“I saw it.”

“You going to turn it off?”

“I’ll try.”

She eyed them for a long second. It wasn’t mistrust, not exactly; more like an x-ray to see if there was a spine. “There’s a baby in my house,” she said. “There’s a husband who sleeps in the day. There’s me, who wants to see darkness when the sun goes down. I don’t live at the corner of Las Vegas Boulevard and a mistake. Fix your light.”

“It’s not my light,” Ren said, then realized how true and how useless that was.

She tilted her head. “It is now.”

Ed came over with a ladder he’d named Louise. “You gonna pry that thing down?” he asked. “Because I would love to see it die.”

“It’s live,” Ren said.

He listened. “Okay, yeah,” he said, a grudging respect. “I thought that was tinnitus.”

They hunted for a shutoff. There wasn’t one. The sign looked like a relic dragged from a diner bulldozed in the seventies, married to a snarl of Christmas lights and extension cords, the old white kind whose jackets go brittle in cold and whose tiny mouths are prepared to bite you. The cords went under the fence and into the next yard, and then back, and then into a junction box on the opposite side of the yard that should not have existed and did. Ren found a cord that vanished into a hole drilled through siding with the sincerity of a shotgun slug. They peered inside with a flashlight and saw a nest of wire so promiscuous it made their teeth hurt: lamp cord spliced to speaker wire spliced to something that had once been orange and now looked like boiled shrimp. It had the unkillable logic of men who believe electricity is a vibes-based discipline.

“It’s Danny,” Ed said, with the shrug we reserve for people who are gone but not forgiven. “He had a lot of ideas.”

“What was it for?”

Ed scratched his jaw. “Art,” he said in a credit to Danny’s stubbornness. Then: “Maybe he liked to know he could be seen.”

For three nights Ren tried to make the light keep office hours. They’d flip breakers until they found the circuit that hushed the hum, then tape the handle down and go to bed smug as a cat. In the morning the sign would be shining again like a witness. The house insisted on being open. Ren stopped promising Geneva anything but attention.

On the fourth night the helicopter came.

It arrived the way helicopters always do in city air: as a verdict, then as a suggestion it might leave if you behaved. It swung in a loose oval over the block, a bullhorn voice rubbed in gravel giving instructions that assumed everyone was already obedient. Searchlights panned over backyards, caught for a moment on a child’s bicycle, a frozen tarp, the wet black of a cat. The beam found the sign and watered it. Ren felt the hum change. It turned greedy, like a choir finding its note.

They went out into the yard because they always went out into the yard. The cold bit and they let it. The beam made the ivy into stained glass. The OPEN sign looked like something a god would wear to a wedding. The hum ratcheted to a pitch that made Ren’s molars whine.

“Yo!” Ed shouted from his yard, pointing up like you do when life gets taller than you. “Hey! It’s this!” he yelled to the helicopter, which did not and could not hear him. “It’s our—” he groped for the right preposition—“this!”

Geneva came out with a robe that made her look like a judge. “It keeps my baby up,” she shouted, because sometimes you shout at the sky.

Ren went around the fence to the side yard where the cords made their promenade. That’s where Saul appeared, drawn by the noise like an old dog by a thunderhead. He had a beer in his hand and no socks. “You want help?” he asked, which in Saul’s language meant, Let me be part of the story you will tell later.

“Don’t touch anything,” Ren said. “I think it’s live.”

“It’s always live,” Saul said, and knelt anyway.

“Hey,” Ren said, a warning wrapped in a plea. “Seriously—”

He was in the process of making the sign of the cross with the tip of a screwdriver, which was the kind of joke men like Saul make when they are afraid of looking afraid. The screwdriver kissed an exposed strand. He stiffened. It was small at first, a little statue frozen in admiration, then full-body. Both his arms locked at the elbow; his mouth opened on a noise that sounded like a word and came out as “uh.” His eyes did a fraction of a roll.

“Saul,” Ren said, very calmly, because calm is a trick you can play with your voice that tells your hands they know what they’re doing. “Saul. I’m going to push you.”

He did not nod because he could not, but his face made a yes.

Ren put their hands on his shoulders. “Not the arms,” they said aloud to themselves, because it helps to narrate your own competence. “Never grab the arms.” They shoved. His torso gave; the arms did not; the screwdriver snapped out of the bright bit like a toothpick from a shark and fell into the mulch. Saul gasped. His fingers stayed clawed for a long dreadful second and then softened like seaweed. He laughed in that thin post-panic way men laugh at barbecues when they have not yet admitted what almost happened.

“Okay,” he croaked. “Okay. That woke me up.”

“Go inside,” Ren said. “Drink water with salt.”

He grinned. “I got salt,” he said, meaning tequila, and staggered away, a man who had either learned something or nothing.

Ren turned to the cords. They were moving. Not just vibrating with current—moving, subtly but unmistakably, like something sniffing for a hand. The Christmas light strands writhed against each other, the white extension cords turned on their bellies, the plug heads clicked their tongues. The sign’s hum resolved into a tone they wanted to call hunger.

“Ed,” Ren said, and their voice came out lower than they expected, the way a voice does when it has borrowed someone bigger. “Get me gloves.”

“What kind?”

“Thick ones. Leather. The ones you’re proud of owning.”

He ran and returned with welders, the ham-sized gauntlets he used when he made yard art out of brake rotors. Ren slid into them like a knight. The world narrowed to the horizon of their hands.

There are techniques to dealing with bad wire. The trick isn’t force; the trick is decision. You separate feeds from returns. You starve a loop. You don’t make a perfect plan; you make a first cut. Ren found the junction where two extension cords had married without benefit of clergy and put a gloved thumb under the cheap plastic coupling. It bit. They tightened their grip until the gloves squeaked. They pulled. The plug fought like an eel. The hum slid up half a step. A spark trotted along the cord and died like a sugar ant in the seam.

“Come on,” Ren said, to the wire or to themselves. “Come on, baby.”

They wrenched the plug out. The sign’s light dipped, rallied. Another coupling became visible in the ivy, the way rot reveals rot. Ren grabbed it and ripped. Another. The cords bucked like snakes, not metaphorically—like snakes. The white jackets made a soft hiss against the fence metal; the twinkle lights blinked in a pattern that would make sense if you were a moth or a ghost. Ren got a hand under the OPEN sign’s transformer box and felt it tremble like a throat. They yanked.

The sign wailed. It wasn’t sound; it was the cessation of sound. The neon guttered from cobalt to pink to the dead clear of glass. The hum dropped like a ball through stairs. The yard felt physically bigger, as if something had unclenched.

And then it was just dark.

For a moment no one spoke. The helicopter, cheated of its favorite target, moved its beam away with a kind of offended dignity and went to go scare some other neighborhood. The cold returned as if it had been waiting its turn. Ren heard Geneva exhale a wordless prayer you could pour into any god-shaped container.

Saul leaned against the fence and shook his arms like he was trying to fling bees off. “That was not my smartest,” he said, with the stubborn glee of men who will always turn a near-death into a story. “You’re a beast,” he added to Ren, which wasn’t the word they would have chosen but was not unwelcome.

Ren set the OPEN sign down on the frost-killed hostas like a thing you’d lay a child on while you checked its pulse. The transformer still ticked gently, like a contracting engine block. The halo was gone. The ivy looked like ivy, which is to say, impudent. The backyard had returned to being a place where human life happened: grills with covers like tarps over cars, cracked planters, a sled without a rope.

Geneva wrapped her robe tighter around herself and came closer with the wary gratitude you reserve for people who have surprised you. “Is it done?” she asked.

“It’s quiet,” Ren said. “There’s still danger, but now it’s only the kind that calls for regular electricians.”

—

In the morning the block did what blocks do after a war that lasted half an hour. They gathered, they inspected, they explained to each other what they had seen. The helicopter had become three helicopters. The sign had been ten feet tall. Saul had died and returned. Ren had barehanded a live wire and wrestled it to the ground. Geneva had composed a sonnet that made the bulb in the streetlight blush.

Ren sat on the back stoop and let the coffee thaw their teeth. Their gloves lay on the step like the heads of animals you would bring to a king. Their wrist had a tidy slice courtesy of the window they’d broken the day before. They’d taped it with blue painter’s tape because that was what their hands had found.

Danny appeared around noon, the way exes appear: because they were called or because they had a feeling. He looked smaller in the day. He squinted at the sign like it had insulted him. “You took down my art,” he said.

“It was on,” Ren said.

“It’s a switch-leg,” he said, as if that explained faith. “It comes off the compressor call. When the heat pump fired, the sign fired. That way I knew if the heat was running.”

“You put a neon sign on your fence to tell you if the heat was on,” Ren said, respectfully.

“It’s more complicated than that,” Danny said, which meant it wasn’t. He peered at the transformer the way men peer at their own decisions. “You didn’t have to rip it.”

Ren pointed to the scorch on Saul’s screwdriver. “It wanted blood,” they said.

Danny shrugged like a man who had given up on the idea that cause and effect were married. “Well,” he said. “Don’t let the city see that on the curb. They’ll write you up for improper disposal of happiness.”

When he was gone, Geneva came with pound cake on a paper plate, the social contract in icing. “I slept,” she said simply, as if confessing a relapse. “The baby slept. I forgot how to sleep.” She handed them the plate like a diploma. “You did good.”

Ed and Saul lugged a contractor bag of wire out of the ivy and into the alley, the way men retire a flag. “I got a guy,” Ed said. “He takes copper like communion.” He looked at Ren. “You got a guy?”

“I’ve got time,” Ren said.

And that, more than anything, is what a haunted house demands. Not bravery. Not money. Time enough to negotiate with the old sins someone else soldered into the walls. Time to learn how this house likes to be touched.

—

They found the rest in the weeks after: the tape-to-tape splices behind a stapled calendar in the pantry, the outlet in the attic that was live only when the bathroom light was off, the three-prong receptacle grounded to a water pipe that had been capped twelve years ago. They found in the basement a panel that had been a panel once and now was a suggestion with a door, a hundred amp main feeding subpanels that made the sort of sense you get when a man believes breakers are feelings.

They pulled lines and measured loads and made charts. They did it without hurry or drama because drama is for nights and charts are for day. Ed would wander down with a beer and watch like a man at a museum. Geneva would send a teenage cousin with a hammer and the instruction to learn something useful. Saul would return with the screwdriver with the burn mark on it and call it his stigmata.

Sometimes, when Ren worked in the empty living room, the light shifted and they would swear the neon had found another way to hum. They’d pause, listening for God, and hear only the state. The heat pump would catch, the blower would wheeze, and then, like a runner cresting a hill, the air would even out. The thermostat would drop from its aspirations to the truth. The house would take the correction without apology.

On a Sunday, Geneva waved Ren over from her stoop with the gesture of someone shooing a cat. “I’m going to say something nice and then something else,” she warned.

“All right.”

“You did right by that thing. The sign. It was a devil. You cut its throat.” She nodded, satisfied with the poetry of that. “Now,” she added, “I need you to stop by after dinner and see about my porch light.”

Ren laughed because this was how neighborhoods stayed neighborhoods. You exorcise one monster and earn ten ordinary chores. “I’ll bring a ladder,” they said.

“Bring patience,” she said, “and one of those bandaids that hold when you sweat.” She looked at their wrist and frowned in the maternal universal. “You shouldn’t tape skin with paint tape.”

“I used what I had.”

“That’s how you got here,” she said, not unkindly.

—

Spring uncorked the earth like a bottle and water rose from places Ren hadn’t known water lived. The wine cellar heaved. The heat pump went honest enough to deserve its name. The grass remembered what it was for. The OPEN sign slept like a saint. Ren hauled it into the shed with the three-headed door and leaned it against a wall. Once, late at night, they swore they heard it hum in its sleep. They let it.

When the city inspector came—called by someone who believed justice tastes better when delivered on paper—Ren showed him the worst first. They had learned that from doctors and cops. “These splices,” the inspector said, polishing his bifocals with a handkerchief like an accusation. “You know you can’t—”

“I know,” Ren said.

“These neutrals,” he said, sighing the way old men sigh at young men in borrowed cars. “You can’t—”

“I know.”

He peered at Ren over the lens. “You new here?”

“I’m in the middle,” Ren said.

The inspector grunted, scratched his notes with the kind of pencil you could use to stake a vampire. “You got someone?”

“Two someones,” Ren said. “A licensed electrician for the panel, and a church of neighbors for the rest.”

The inspector’s mouth twitched. “That’s what I like to hear,” he said in the tone of a man who doesn’t like much. He left a paper that said FIX and a date that said SOON. Ren taped it to the fridge where it could learn patience.

They slept badly the night after the inspection because sleep is a contrarian. Sometime after three a.m. they woke to a noise that was not the sign, not the blower, not the house’s old language. It was a helicopter that wasn’t there, a remembered bullhorn, a phantom hum. They stood in the yard barefoot and waited to see if memory would make itself flesh. It didn’t. The sky was dumb with stars. The ivy was just ivy. They laughed aloud at themselves, the harmless madness of people who have decided to live.

In the morning Geneva sent a text with a picture of her baby sleeping in the proper dark, one fist curled under her face, the other splayed like a starfish. You did that, the caption read. It was the first time in months Ren felt credited for anything that mattered.

They made coffee. They stood at the back door with the mug in both hands the way people do who have decided to stay. The house breathed, slow and even. A faint ticking came from the shed: a transformer cooling, a memory cooling, the sound metal makes when it learns about winter.

Ren smiled to themselves and, for once, felt no need to narrate it. The hard work had been done. The rest was up to regular electricians.