Editor’s Note:

Per the usual, as you ought to know by now, the events of this story are true. The names have been changed, for the sake of the innocent — and the dead.

This is the final chapter. Everything that comes after this is a different story. Maybe we’ll tell it later. But none of the characters in this story are children after this point.

Chapter VI: The Last Straw

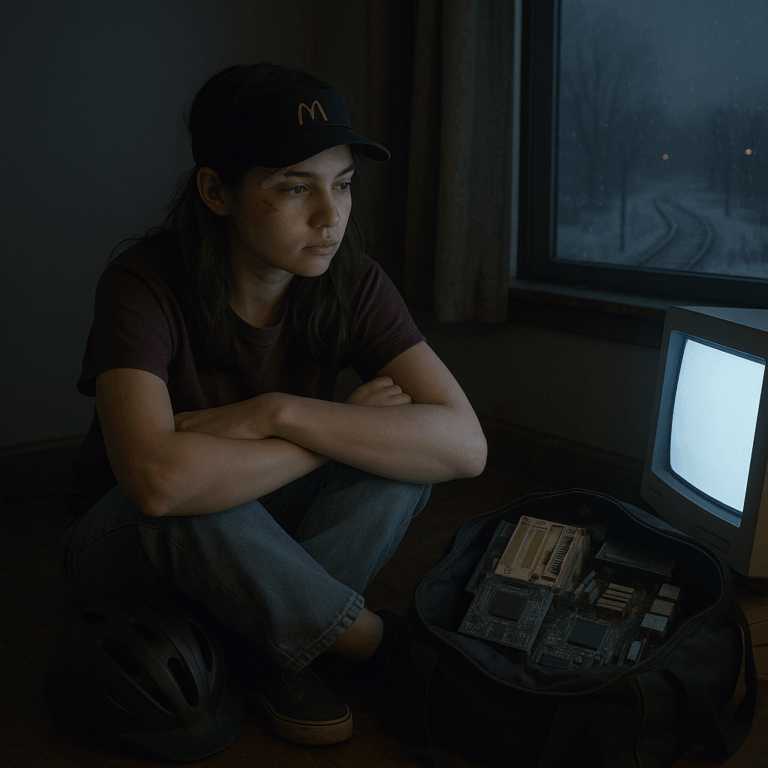

Hunger is a teacher, but not a kind one. After the computers and the winter of cold rooms and fryer air, starvation did the simple arithmetic that pride refused: you can’t live on free McChickens and milkshakes, not when the stove is dead and the landlord is a philosophy. Doc moved back home because bodies make decisions that brains only later ratify. She told herself it was temporary. She told herself a lot of things.

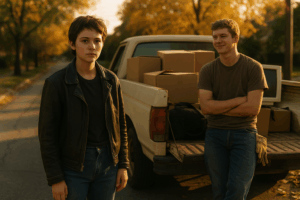

Bill showed up with a pickup he’d bought with cash from mowing other people’s lawns into geometry. He parked at the curb, engine ticking pleasantly, and climbed out carrying a pair of work gloves and the kind of smile that kept assuming good outcomes. He was the only person in town who matched Doc watt for watt and refused to make that feel like a competition. While she’d been alone he’d called most nights—electric, dry-witted confessions traded through a long curly phone cord like contraband. He lifted boxes like he was solving equations.

They loaded her life in twenty minutes: books, the duffel, the computer guts, a milk crate that still smelled like the river. When they finished, Bill leaned on the tailgate and said, careful, “There’s this girl.” He named her crush from two years back as if it were a country he’d only just learned to pronounce. “Is it… okay if I try? I mean—should I?”

Doc looked at Bill’s hands on the metal, the unassuming competence. She thought about the way he listened when she talked about pumps, about the way he got quiet when silence was smarter. It was so almost-something that it made her chest feel complicated.

For a moment, she briefly considered saying, Why not me?, but then didn’t.

She pulled the wrinkled condom Ricky had slipped her—a mean joke, a dare—and tucked it into Bill’s shirt pocket with two fingers. “Go get her, tiger,” she said, and immediately wanted the line back, but his blush and laugh made it perfect for a moment. They drove to her parents’ with the windows down, hair and evidence of competence blowing everywhere.

After they’d unloaded the truck, they never spoke again.

Two days later, a knock pulled the house up on its haunches. René stood there in uniform that made him look both older and smaller, a zipper at his throat he kept touching as if it were a rosary. His eyes had that baked-in red of men who’ve had to convert a body back into a person, if only long enough to say the name. He didn’t step in. He said it on the porch, voice stripped of all ornament. A crash outside of town. Fast. Bled out in an all-at-once way. He’d rolled up first, done what you do, did not know until the wallet. Bill behind a laminate face, some DMV photographer catching his bad side and a tilt of his mouth that still said maybe.

Doc’s brain stuttered. It tried to build a timeline with no time in it. She understood the mechanics before the feeling—momentum, steel, force vectors, the way glass is obedient until it isn’t. Then the feeling found her. It arrived like winter and stayed.

The funeral treated her like everyone’s least favorite rumor. She attended the viewing and looked at a face arranged by professionals into the suggestion of sleep and wanted to shake the whole room until it admitted the lie. At the burial she wasn’t welcome—too distant a connection, too much trouble—and when she tried to find the cemetery on her own she got twisted around by detours and came home with dirt on her shoes and rage in her teeth.

She stopped going to school because the bell had become a punchline. She learned the exact geometry of her bedroom ceiling from the bed. At McDonald’s she moved through the motions like a metronome. Grease climbed into her hair and sat there like a fact.

Spring arrived with charm and nothing else. Doc’s hair grew long because it could. She found an almost-orange leather jacket at a thrift store that made her look like someone whose edges were finished. “Not giving a shit” turned out to be less a philosophy than a permission slip: stop making yourself small for people who like you that way. She wore her scar openly. The adults who’d told her not to apply to college got the same look she gave broken machines right before she decided whether to fix them.

Peachy made himself a movie. He’d been tacking pieces of other men’s heroics onto his bones for months, but now the costume stuck: a Christian Slater anti-hero grin, a monologue cadence, a soundtrack audible in the way he moved. He was both more there and less reachable. Ricky, jealous of every room’s attention, staked a claim on a freshman he’d asked to prom with borrowed confidence and a fast-food paycheck. Peachy bristled on principle. Doc recognized the girl in a sideways way—her face tilted toward the version of the world where things work. Doc wanted her too, in an abstract future they weren’t going to live in yet, but she was busy carrying a grief shaped like a person she’d accidentally blessed and then lost.

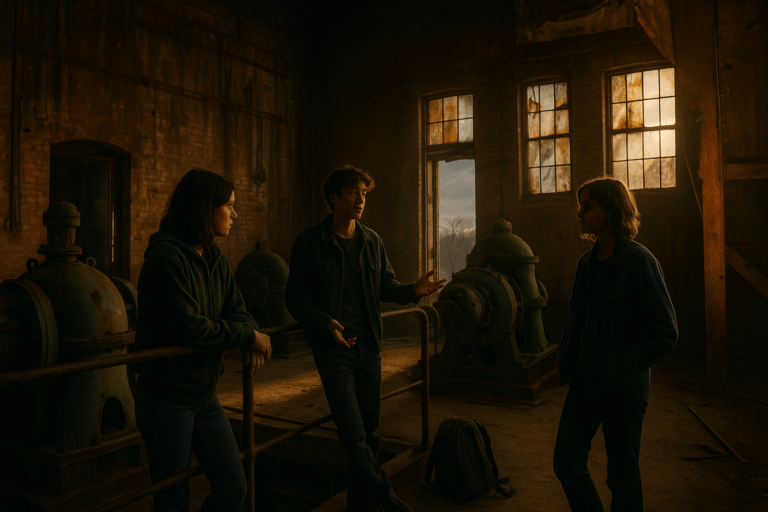

One afternoon, with no special ceremony, Doc told Peachy he was acting crazy. She didn’t say it to wound. She said it the way you tell a person there’s a cliff behind them. He smiled askew and said he was fine. He wasn’t, and neither was she, and that’s how childhood ends: not with a moral, just with two people insisting to each other that they’re okay because the truth would require new names.

She didn’t repeat senior year. Four years was comedy, not persistence. When the counselor called her in to pronounce that wisdom, Doc nodded as if the words had been hers. The counselor blinked, robbed of the pleasure of a lecture, and sent her on her way with a sheaf of forms whose edges didn’t cut half as well as they wanted to.

Jill called in late July. Her voice carried a tremor that was almost joy and almost terror. Pregnant, she said, with the other Richard’s baby. For a second Doc’s stomach went elevator-empty. She pictured futures that ended in rooms with plastic chairs and futures that never quite started. She made herself breathe. “Okay,” she said, and meant it. She called Arnold, who had a gift for logistics, and Alex, whose talent was saying yes before the question was finished. They promised rides, money, days off, a schedule that could get Jill through the appointment and out the other side with the least possible scar. It felt almost adult to plan it right.

Then, like a cliché you don’t get to laugh at because it’s yours, Alex and René decided to rob a convenience store. Not much—just enough for cash to cover procedures and gas. Doc stared at them while they told her the plan, which was not a plan but a vibe. “Have you learned nothing?” she asked. Their smiles faltered in tandem, which would have been cute if it weren’t infuriating. “From Ricky and Wolf? From alarms? From gravity?” René tried on the boy he’d been and said they had it under control. Doc told him control wasn’t a verb you get to declare and walked out before the conversation could collapse into pleading.

Jill’s appointment came on a hot day the air conditioners were losing to. They got her there and home again because some things you do right even when the world will not award you points. Doc watched the ceiling fan turn without moving air and understood that survival was not a story; it was a practice.

On the morning Doc left, she didn’t make a speech. She folded her life smaller than a life should fold. The duffel swallowed one machine and some books and two shirts that made her feel like someone who could eat breakfast without rehearsing. Her mother was in the kitchen with a newspaper she never read. Her stepfather wasn’t home, or he was and chose not to be. The house smelled like old coffee, cat piss, and whatever else had soaked into the baseboards since she’d been thirteen. Doc put her palm flat to the doorframe the way she had at the pumping station and thought about thresholds and what they owe.

At the bus station, the light felt Midwestern though they weren’t in the Midwest. Everything was beige and humming. A television bolted to the ceiling played news without sound. A woman slept with her cheek pressed to a suitcase hard enough to leave a mark. The clerk slid her a paper ticket with holes along the edges that asked to be worried into confetti. Doc bought a coffee that tasted like forgiveness and salt, sat by the window, and caught her reflection in the plexiglass. She looked like all her decisions at once.

Peachy showed up with a plastic bag of snacks and a look that couldn’t decide between anger and pride. They stood there with the vocabulary they’d rehearsed on rooftops and bridges and finally admitted it wasn’t going to be enough. He said he’d write. She said he wouldn’t. They both smiled and let that be the truest thing in the room.

He shifted on his feet. “I heard you called Bill your best friend,” he said lightly, as if asking about the weather. The light tone sat over something darker.

She opened her mouth to explain and found there wasn’t a word for how two orbits can both be true without touching. She squeezed his shoulder, just a little. “You were the person who was there for me,” she said. “He was the person who saw me as his equal. It’s not a competition.”

Peachy nodded like maybe it was anyway.

For a short moment, Doc felt a brief pang of regret. If only–if circumstances had been different. What was this feeling exactly?—another crush, like the one she’d handed over to Bill just before… No. Don’t think about it.

The bus announced itself with a sigh big enough to pass for mercy. They hugged one last time, and then parted.

Out past the edge of town, the river shrugged under the bridge as if it had always been someone else’s problem. The business park slid by with its microwaves and chemical flavors and ladders to little gods. The pumping station’s stack poked up above the reeds, a blunt finger from a forgotten prayer. She watched the smokeless chimney until it dropped out of sight and kept watching the place it had been.

The road west has its own kind of sky. Out there the horizon is a sentence you can finish. Doc sat with her head against the glass and thought about Bill’s hands on the tailgate and René’s fingers on a zipper and Peachy’s laugh arriving too late or too soon. She tasted fryer salt and grief and the afterimage of ozone. She thought about the joke she’d made with the condom and how the universe does not accept tips. She thought about the pump’s hum and the Chinook’s low complaint and the way thunder can punch a body without bothering with lightning. All the sounds braided into a single note that wasn’t pretty and wasn’t not.

She let herself say it then, under her breath, to the reflection and to the girl who used to sleep in rooms that didn’t remember her: “Bill was my best friend.” It wasn’t a downgrade for Peachy; it was an indictment of fate. She thought about how different their worlds had always been—one built of grades and jokes and late-night logic, the other held together by myth and hunger—and how she’d been trying, all this time, to be fluent in both. The bus hummed. The seat ached. She felt bad, the good kind of bad, the kind that teaches rather than bruises.

Somewhere a state line crossed under her without incident. She leaned her forehead to the glass and kept her body. She kept all of it. The future didn’t make promises. It never had. But it did make space, and for the first time in a long time, space felt like something other than absence.