Editor’s Note:

Yeah, so this one hits a little harder and closer to home. Yes, the events are still real. Yes, more than one event is smushed into a single climax. No, I am not taking any of that back. Spoiler warnings for domestic violence: if this makes you uncomfortable, then good; it made me uncomfortable too, to say the least.

Chapter V: The Blows at Home

The phone rang too late for good news. A cheap cordless, the kind with a rubberized back that stuck to sweaty palms. Doc thumbed TALK and said hello and got a long cassette-squeal in her ear—fax tone, no voice, the kind of sound that turns the air in a house hostile. She hung up, set the phone on the counter, and the light blinked again. The same call. The same shriek. A joke, a misdial, a machine trying to talk to a person?

From the hallway: “Who the hell is calling at this hour?”

“I don’t know,” she said, and the machine screamed again. She added, because truth never helped in this house, “It’s a fax.”

“What?” Footsteps. “What did you do?”

“It’s not me,” she said. “It’s just—”

He was in the kitchen now, breath already wrong, the way breath gets when anger hitches onto it like a parasite. The cordless squealed a third time. He grabbed it, stared at the blinking light like it owed him rent, stabbed END with a thumb and flung the phone onto the counter. It clattered, slid, thumped to the floor. The sound was somehow an accusation.

“Turning it off,” he said—an announcement in lieu of apology. “You don’t let people call here like that.”

She laughed once. It wasn’t the wise move. “I control telemarketers now?”

He reached for the phone. She reached for it, too. Their hands touched. It wasn’t a tussle; it was a tangle. The phone fell again, battery cover skittering under the stove. There was a click in him—audible, moral—and then the room narrowed until it was mostly his hand and her throat.

The lift was clean, practiced in some other life, a bouncer’s motion grafted onto a kitchen. Her heels left the vinyl by an inch. Wall at her shoulder blade; cabinet pull digging into her back. His thumb pressed under her jaw, two fingers at the side where pulse and panic meet. The body is a very old animal. It tried to make her smaller so air could go around his grip. He brought her up that little inch and she had a flash of the truss bridge at high tide, that exact, suspended not-yet, and then the world tunneled to sound: her own breath finding a thin passage, his breath thick and close, the soft fizz of the refrigerator motor that had never seemed louder.

“Watch your mouth,” he said, and she nodded because nodding made his fingers shift, and shifting meant air. He didn’t like the nod. His other hand came up fast as a hinge and her forehead met the heel of it with a flat, wooden thock. Light behind the eyes, then red, then hot, then wet: blood rolling down into the corner of her glasses and turning the kitchen into smear and shine. The pain arrived clumsy and late, the way pain does when the body is busy with oxygen triage.

He dropped her like she was an argument he’d won. She hit the floor on hands and knees, palms grinding on vinyl that always felt faintly greasy. Her breath came back with a whistle that belonged in a bird. Her glasses were smudged, one lens sprayed. Blood ran along her eyebrow into the hinge of the frame and down her cheek like a road that someone else had planned. She slid backward with the instinct of an animal that knows distance is medicine. His shoes stayed where they were.

“Get up,” he said. It wasn’t a request. “Don’t you bleed on the floor.”

She stood—too fast—and the room lurched. The counter edge caught her hip. She grabbed a dish towel and pressed it to her brow and the towel went maroon in a heartbeat. She made herself look him in the face through the red blur because she had learned that looking away was an order she no longer took.

“Okay,” she said. Her voice was raw. “Okay. I’m leaving.”

“You’re not,” he said, but it lacked conviction. It sounded like the thing a man says when he needs the world to stay arranged around him.

She stepped past him into the hall and his hand snagged her sleeve without commitment. She pulled free. He said her name the way someone calls a dog. She walked out into air that tasted like pennies and late leaves and cold already starting even though it was only September. She did not slam the door because making noise felt too much like telling.

On the sidewalk the blood cooled and thickened and the sting sharpened around the edges into something obscene and intimate. She kept walking. One block. Two. The streetlights did that sodium trick of making everything look tired. Wind lifted the towel and a drop fell to the curb and burst like a tiny, impatient star.

The first police car rolled up slow, an apologetic blue. The officer was younger than she’d expected, older than he had any right to be. He looked at her face, then at the house behind her, then at his own shoes. “We got a call,” he said, even though she hadn’t called. Maybe a neighbor. Maybe the fax machine finally found a human.

“Okay,” she said.

“You live here?” He gestured at the house as if it might deny it.

“Not anymore.” She felt reckless saying it. Recklessness felt like oxygen.

A second car, then a social worker: sweater, clipboard, the tired smile of someone whose job is to keep people from drowning in paperwork. They asked her to come inside. She told them no. They asked what happened. She said what happened. The social worker wrote it down as if the graphite could hold any of it. The officer went to the door. It opened. Voices in low, manly register. The officer came back with a shrug that somehow felt like a verdict. “Maybe,” he said. “Maybe not.”

The social worker said, “Is there somewhere else you can stay tonight? It’s late.”

“At a friend’s,” she said, because the other option was the hospital or the station or the guest room where you sit under a buzzing glass square and learn how to fold yourself into the shape of a form.

“Good,” the social worker said. Relief like a closing file drawer. “Let someone clean that cut. You might need stitches.”

She didn’t. Or she did and decided not to. She wrapped a fresh towel around her brow and walked to Peachy’s because that’s where her feet knew to turn. He answered in sleep-soft shorts, eyes going wide and wet in the doorway. “Jesus,” he whispered, not as a prayer. He pulled her in and pressed another towel to her head and said he’d kill the man, and she said, very calmly, “Don’t,” and he didn’t, because their covenant with the world was to survive it, not to fix it.

She woke on his couch with her head feeling two sizes too large and the towel glued to her. When she peeled it away the wound yawned at her in the mirror: a bright red crescent above her right brow, neat as a notation. She pressed it closed with butterfly bandages the color of surrender. She held her glasses up to the light and rubbed them clean until the kitchen, the hallway, the officer’s mouth all returned to focus as if they’d been waiting for permission.

School started the next week as if nothing had happened. Early fall sunlight that made everything look possible. A locker that wouldn’t shut. A guidance counselor who had always been a little bored with her and now seemed actively annoyed. Doc used to hustle the report-card game—As where it counted, Es on assignments she refused to do, a pattern the system tolerated as long as it could call her gifted. Now the pattern stopped being cute. Teachers stood in doorways with their arms crossed and said she was “underperforming.” The counselor smiled the way you smile at a cat on a high shelf. “Let’s talk realistic expectations,” she said, which meant don’t bother with applications, which meant we don’t know what to do with you and we never did.

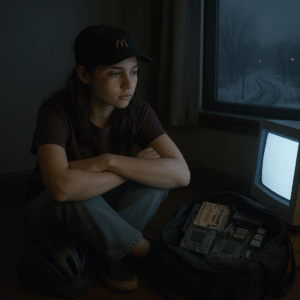

On Saturdays and most weeknights, McDonald’s. The fluorescent hum and the fry timer’s metronome and the caffeinated management logic that could not be argued with because it had no author. She leaned into the heat until it leaned back. Five hours or more and you earned a free meal, which meant she learned the math of hunger. McChicken. Fries. Vanilla shake. You could sneak a fajita if your hands were quick and your face was calm. Salt settled into the seams of her skin. She pedaled home at midnight on a bike older than she was and felt the air move around her like a kind of mercy, and still, by the time she reached the door, the fryer smell had found her again and sat on her shoulders like a stranger who wanted to be friends.

She hated it in the particular, private way you can hate something that’s saving you. The grease climbed into her hair and set up camp. A girlfriend would never come. A boyfriend either. Kissing with that smell on you felt like asking someone to press their mouth to a filter. Sometimes she let herself think: if the world had been different—if winter had been kinder and spring less poisoned—maybe Peachy could have been the person who made the smell not matter. Then she told herself to cut it out. The story had not chosen that version.

She slept sometimes at Peachy’s, sometimes at a friend’s up the street, sometimes in a spare room at a house where the host turned the furnace on only when the threat of burst pipes outweighed the threat of a high bill. You learn a lot about yourself when your breath shows indoors. The stove died in November and stayed dead because the landlord had the same theology as the furnace man. The room held its temperature like a grudge. She learned to reheat soup with a heat gun and a ceramic mug and a towel like a potholder. She learned that hunger and pride share a border and it’s easy to step back and forth without noticing.

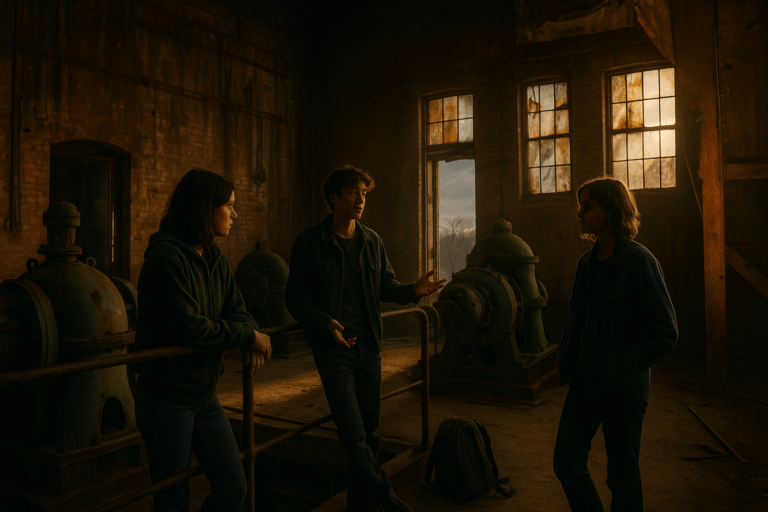

René came by twice, maybe three times, lighting the room with his patter and then dimming it with the way he looked at the door while he talked. He told her stories about the pumps and half-true plans to unionize the fry cooks and a dream he had about riding the Chinook’s belly like it was a carnival ride. He didn’t ask about the scar; he looked at it, then at the ceiling, then said something funny and left the funny hanging in the air like a balloon on a string. Peachy came and sat on the floor and leaned his head against the bed and said nothing for long stretches and then everything at once.

One evening, a call: a voice she’d known since third grade, now pitched high and thin: “Did you hear? About—” A name. A boy from school. Not one of theirs. Not cruel, exactly, just the kind of person who walked through life as if everyone else had to jump aside. Doc held the phone. The scar tugged when she frowned. “And?”

“He died last night,” the voice said, pleased with the gravity of its own sentence.

“Oh,” Doc said, and the word came out cold. “I didn’t like him.” It was unkind and it was true and it was the wrong thing to say and she said it anyway because grief hadn’t yet put its hand on anyone she loved and because kindness had turned into a pair of shoes she couldn’t find in the dark. After she hung up, she felt the meanness of it settle on her tongue. She promised—quietly, to no one—that next time she’d find a gentler word. This is how foreshadowing works in real life: a private vow you only understand later.

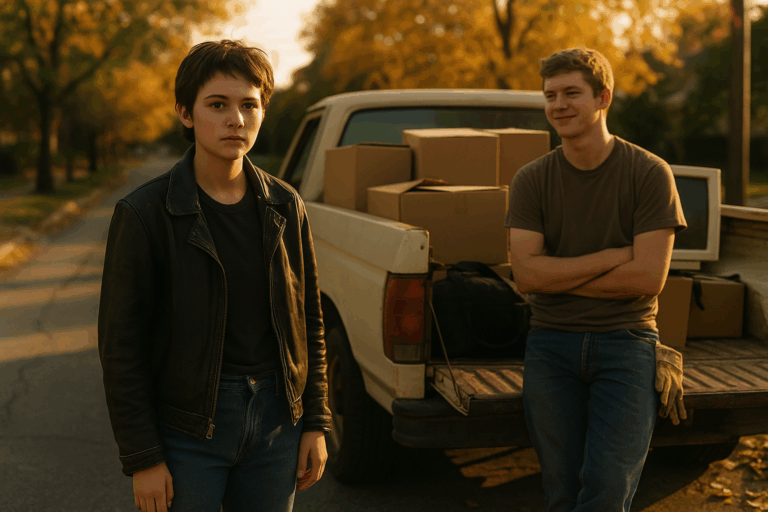

Ricky and Wolf came on the coldest night of December, loping trouble in thrift-store hoodies. Not their real names, of course—she wouldn’t give them that dignity. Ricky had the eyes of a dog that learned every trick except sit. Wolf was one of those boys who invent a legend to fit an emptiness and then live inside it until it cracks. They had an opportunity, they said: a little office in the business park, the one with the microwave research and the BMW roof, some computers left overnight, no alarm worth speaking of. They had a plan: in and out, quick, no damage, split three ways. René wasn’t invited. Peachy wasn’t either. This was the kind of stupid that required a very specific flavor of confidence.

They cased it like children do: a loop in a car too loud for stealth, a flashlight beam that wandered like a drunk idea. Doc watched with an old, cold patience, the same stillness she used for trains. At two a.m. the three of them stood in the shadow of an HVAC unit and Ricky used a screwdriver like it was a wand. Wolf held the bag and the bag was empty and would stay empty. Inside, a motion sensor blinked a red dot as if in applause. A security light popped on; an imagined siren began screaming in all their heads. Ricky ran first. Wolf ran better, given he had a car. Doc stood for a half second longer than was intelligent and then walked away, not running, because a person who runs announces guilt.

The next day she watched them brag about how close they’d gotten and how the alarm had been “military grade” and how only a fool would have tried to push it. She looked at their moving mouths and felt the fryer smell in her hair and the scar itching in the dry heat and something in her went beautifully quiet.

She went back two nights later alone. No Ricky. No Wolf. A backpack with tools that weren’t expensive enough to be called a kit but were sharp and honest: a better screwdriver, a set of shims, a length of braided line, a flashlight she’d taped to mute the lens flare. She wore gloves. She wore the same bike jacket she wore to McDonald’s, because invisibility sometimes looks like a uniform.

She moved like someone who had learned how to be a system. Fence, gap, crouch, wait. The window they’d jimmied sat sulking under a lip of concrete. She listened for the sensor’s blink and learned its patience: count to six, move on seven. Inside, the office smelled like dust that had learned to type. She did not hurry. Hurry is for children and alarms. She found the tower units by feel and weight and need. She unplugged cords the way you unhook bones. She set each machine on a folded towel and slid it gently along the carpet to the open window. She breathed through her mouth to keep her breath from fogging the lens of everything.

Three towers, one monitor, a nest of cords like long dead snakes. The duffel went heavier than a promise. She left the place better than she found it: chairs set back under desks, a trash can tipped upright with her elbow, a door closed softly with the patience of a person who had decided to be better at this than the boys. Outside, she paused to listen for the one thing that could ruin it—footsteps with authority—and got only wind off the river and the long, faithful hum of the pumps.

She took the tracks home because the streets felt like confession. The rails were honest. They did only one thing and they did it in a straight line. Five miles in the dark is a form of prayer. Each step set a thud into her knees that the body would remember later as weather. The duffel strap bit her shoulder and that, too, was a useful kind of pain. Frost feathered the ballast. The river to her left was a black muscle. Somewhere far off a train sang low and heavy to its own weight and she paused, instinctively, to let it pass through the part of the world she wasn’t occupying. The scar throbbed when the air shifted. She adjusted the bag to her other side and the pain became symmetrical, which felt fair.

At the little truss she ducked under the first beam and climbed the path they’d carved with their bodies as kids, the muscle memory of trespass turning into something like grace. In town again, she kept to the alleys and the negative spaces between buildings, the places where the lights overlap and cancel. The duffel felt like proof: not of cleverness, exactly, but of competence. I can do this, it said, in a voice very much like hers. I can make a system tell me its rules, and then I can win.

Back in the cold room—the one with the quiet radiator and the dead stove—she set the duffel on the floor and leaned her forehead against the window until the glass came away cold. She unzipped the bag. The machines looked like little buildings in a city that had agreed to obey her. She plugged one in and it hummed on, obedient. The fryer smell in her hair was its own lonely weather. She lay down on the floor next to the hardware and watched the power light blink itself into steady. She didn’t feel triumphant. She felt… level. Like the world and she had found a way to stay in the same sentence without arguing.

In the morning, she would bike to school, then to work, then home again through air that held frost like a thought. A counselor would say something bland about her future. A manager would praise her for hitting her drive-thru times. She would smell like fries and owe nobody an apology. Somewhere, Ricky and Wolf would tell a story about a near-miss. The pumps by the river would keep making their tired music. The scar would itch, then settle, then become just another line her face used to tell the truth.

For now, she lay in the cold with the machines warming the room by a degree you couldn’t measure and thought about the night with the fax tone and the hand and the wall and the way the world can make a person weightless for the wrong reasons. She let the thought pass over her and through her like a long freight. She kept her body. She kept all of it. And when the radiator finally pinged once—just once, as if remembering its job—she smiled into the dark, because even broken systems sometimes tried.