Editor’s Note:

The story continues as Doc, Peachy, and René claim a disused water treatment substation as a secondary base. But the harmony they once shared is fractured by the different paths they each take.

Pipes and ghosts, thunder and steel, the old blows to Doc’s head arriving like weather through the new ones.

The story is true, but the events are blurred and distorted.

Chapter IV: The Sky and the Blows

By late summer the pumps had a heartbeat. You could feel it in the concrete before you heard it—a low thud you might mistake for your own pulse until it kept going when you held your breath. The old pumping station sat where the marsh gave up and let the county’s machinery speak, a brick rectangle with a smokestack and pitted windows that glittered like bad teeth. Someone had welded the main door shut years ago, which meant they had to crawl through a side hatch that stuck at the hinge and bit your hips on the way in. Inside it smelled like warm iron and a sweetness that wasn’t mercy.

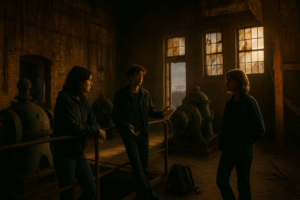

They called it the clubhouse because they didn’t have better words for what they kept doing to their own childhood. Peachy claimed the mezzanine, a mesh catwalk overlooking the big floor where the intake pipes ran like exposed ribs into the concrete trough. René took the office—one grimy window, a desk too heavy to move, a rotary phone long divorced from any line. Doc chose the pit. That’s where the pumps lived: gray-green turbines with number plates like dog tags, flywheels fat as tires, valves that took both hands and your shoulder to persuade. On the far wall a faded stencil still read CHLORINE ROOM; someone had overpainted it with a warning skull in house paint that had slumped and cried.

The first day they got the small booster humming, and Doc felt something crack and align inside them. It wasn’t power; it was order: bearings, alignment, suction head, the fact that water wanted to move if you gave it a reason. They crab-walked around the housing, ear pressed to a screwdriver to hear what the pump said when it worked. Peachy leaned over the rail and called them Captain Nemo. René flicked a switch that didn’t go to anything and declared they were “live to the county.”

The rift started small, like all rifts do. They were sitting on the catwalk with their backs to the cinderblock, sharing a warm bottle of Royal Crown, watching heat shiver above the housings. René tapped out an imaginary cigarette and said, conversational as weather, “You know, if a person wanted to make a point, there are easier places than the river intake.”

Doc stared at him. “A point about what?”

“About how fragile it all is,” he said, not looking at Doc. “All that faith people have in faucets. Turn, water. Magic trick.”

Peachy threw a nut at him. “You’re not funny.”

“I’m not joking,” René said, and there was nothing showman in his voice. “You keep telling me systems are just machines and machines can be fixed. I’m saying they can also be taught a lesson.”

Doc felt the old winter stillness climb up their spine, the kind that had kept them flat under trains and steady over ice. “This place treats water,” they said. “That’s the whole point. You don’t poison the thing that could make it cleaner.”

He shrugged. “I’m not saying do it. I’m saying it’s interesting that you could.”

“I could also put your head in a vise and call that interesting,” Doc said, standing now, too fast, light sparking at the edges of their vision. “I’m here to see if I can make it run.”

Peachy spread his hands, peacemaker by habit. “Hey. Hey. Not the point. We’re here because it’s cool, right? Big machines. Warm air. The world’s guts. Let’s keep the apocalypse theoretical.”

René grinned and the tension slipped away because that’s what he could do. But Doc watched him dial his face like a volume knob and realized they’d started to mistrust the sound.

Also, Doc felt their own re-calibration happening too—slow and soft, internal in a way that didn’t make it into words they’d let the others hear about.

One night, while Peachy was staying overnight, Doc said quietly only, “Sometimes, I think I’d have been better off if I’d been born a girl.” Maybe there was no reply – or maybe Peachy said, “Yeah. Me too.” and possibly didn’t really mean it. Either way, nothing more was said about it, ever.

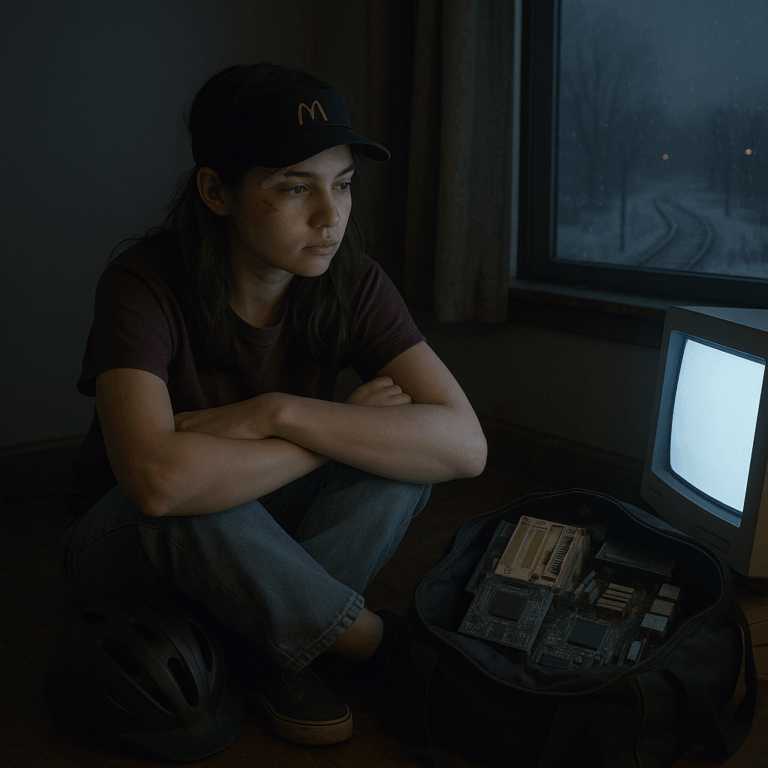

At night, the pumps sang to her after she went home. She’d lie on her back and count the thuds—three quick, one long—and before the rhythm could become a lullaby it would collapse into the old private catalog of impacts. The treehouse first: the afternoon the ladder shifted and she dropped through a frame of sunlight, struck the packed earth with the top of her head and saw the world blink like a camera, then return with the sound turned down. Someone laughed; it might have been her. She’d walked home with dust in her hair and a new caution braided into the old one, the concussion too small for attention and too large to forget.

Then the mountain: not a mountain by adult standards, but the biggest hillside in bus-range, a rock face with a path that teased you upward. They’d raced down in a pack and Doc had clipped a root, pinwheeled into a boulder, and cracked her brow hard enough to make a sound like a door closing. She remembered lying on her side and thinking, distinctly, that she was not in her head but just behind it, looking down at her own ear. When the world clicked back in she tasted salt and pennies and someone was telling her to count fingers. She said “all of them,” which made no sense but made everyone laugh, so they called it good.

The summer made the marsh smell like hot batteries and boiled reeds. Peachy had a crush that turned him into a different animal. She was Pentecostal—hair neat as ribbon, eyes that never admitted humor—and she moved through hallways like a person conducting invisible traffic. Peachy followed at a respectful distance until he didn’t, then wrote her a letter he didn’t deliver and a poem he did, then prayed without believing, then believed without telling anyone. It made him luminous and miserable in equal measure. He talked about hell as if it were a lake he’d learned to swim in. He started taking late walks that ended with him sitting under the little truss, listening for trains like they were instructions.

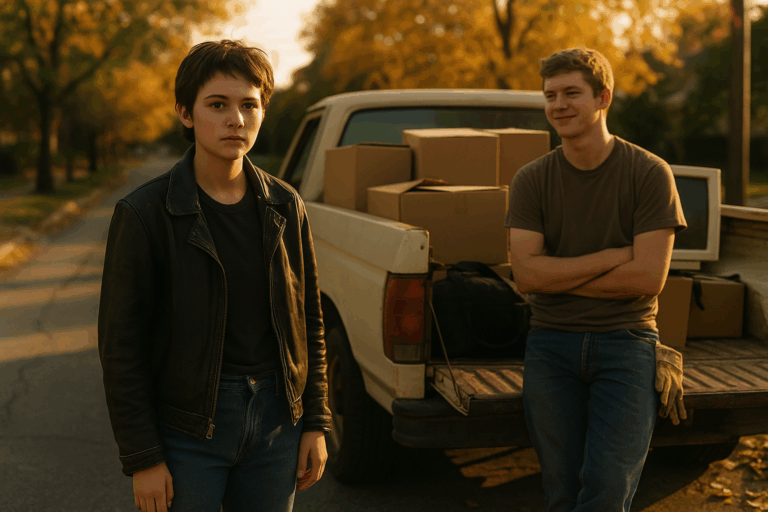

The confession came in August, night so thick with cicadas the air buzzed. He called the house phone at Doc’s and hung up. He called again and said nothing. He called a third time and said, “Can you meet me?”

Doc met him by the cinders where the rails diverged. Peachy was a silhouette with a nervous jaw, hands jammed in his pockets like they were trying to get away. He didn’t look at her when he said, “I think I’m done.”

“With what?” she asked, though she knew.

“Being here,” he said, and the way he stood half on the ballast made the meaning specific. “I’m tired, Doc. The river’s tired. The girl at school says the world’s ending and for once I agree. I don’t want to wait around for the trumpet. I keep thinking—if I time it right. If I… just step. You know? No drama. No mess for anyone who matters.”

The rails hummed with nothing. She stepped between him and the path a body would take to do what he’d said. She didn’t touch him. She said, “Okay. So we walk.”

“What?”

“We walk,” she said again, and started. “You can talk if you want to, and if you don’t, then I will. But we’re going to keep moving until the sun makes this sound stupid or beautiful, whichever comes first.”

They walked the shoulder of the highway like ghosts with good shoes. Tractor-trailers inhaled them and exhaled them. Somewhere past the county line there was a neon sign born to be the end of nights like this. They found it by feeling for warmth through the dark: IHOP buzzing with the kind of mercy that doesn’t ask your age. The waitress had eyes that had seen worse. She poured coffee and called them “hon” and put extra butter on the pancakes without being asked. Peachy tried to pay with quarters; she palmed them back into his hand and said, “You keep those for a day you don’t think you’ll need them.”

He talked in loops and detours and then in plain lines, and by the time the sky went weak gray he was only tired. They walked back the long way—different shoulder, different sun. Peachy went in his front door with the quiet of a person who’s broken and breaking rules all at once. Doc hauled herself through her window on a rope of knotted sheets and lay on the floor laughing through her teeth because she wasn’t sure how else to keep the sound from turning into something else.

The pumping station was still there waiting, shrugging hot air at the marsh like a bored animal. René had turned his talk into theater. He whistled while he worked and tried on voices and told elaborate stories about what they’d do once they “owned the water.” He knew the welder at the auto place, he said; he could get the door cut in a day, easy. He could talk the night guard into believing they were interns on a county program. He could sell the old valves for scrap to buy new gaskets. Doc said the words that meant no without saying no. Peachy showed up late, smelled like coffee and cheap salvation, and watched them with the eyes of someone who’d stood at a fence and decided to step back.

Nights grew full of weather that didn’t break. Doc lay in bed and tried to sleep on her back like a person at peace. She found herself flat and then not flat—rolled to the edge by some muscle remembering a fall. She had read enough to be dangerous and started trying to leave her body on purpose. It wasn’t a religion. It was an experiment. She’d breathe in counts of four, let the pumps’ remembered thrum line up with the blood under her ear, let her hands float as if they were balloons, let the room lose its weight. When she got it right, the ceiling would become proximity instead of distance. When she got it wrong, she’d be halfway to sleep and scolding herself for wanting magic.

The night the thunderclap came, there was no storm. The heat had been holding for days, air stuck in the posture of a punch never thrown. She had just reached that hovering edge—hands weightless, breath a string—when the sound hit the house as if it had been waiting right outside the window. It lifted her whole body off the mattress by a whisker and slammed it back into itself. The window rattled so hard the latch bounced. In the lower corner of the pane a spider cracked a neat star. For a second she was in the treehouse again, behind her own skull looking at her ear. For a second she was on the mountain, tasting pennies and dust. She sat up fast and the room doubled, then clicked. Somewhere very far away a dog barked because dogs will bark at physics if you teach them long enough.

She laughed—a quick, scared bark of surprise—and then cried without meaning to, as if the body had decided to empty something and hadn’t troubled to tell her what.

In the morning she called Peachy and René and said the sky had punched her, and they argued cheerfully about long-wave pressure fronts and freak sonic booms and God having excellent timing. Peachy said he’d had a dream he didn’t want to describe. René said he slept like a saint and none of it mattered because the door at the pumping station still needed to come off if they were going to “civilize the place.” He’d borrowed a jack bar. He’d seen how the frame was already cracked. “It’ll take five minutes and the right leverage,” he said. “Come watch me be a genius.”

They met at dusk because everything important happened then. The marsh was one long exhale of warm rot. The pumps beat. The dragonflies were drunk on heat and aim. Peachy arrived with a gourd under his arm—a hollow thing they’d carved months ago and stuffed with nonsense and a dare. At the time they’d called it a trap for whatever haunted the river. They’d corked it with melted wax and nervy laughter and left it under the mezzanine like a charm a kid pins under a mattress. He’d found it that afternoon, he said, and cracked it. “Bad luck to keep a thing like that closed,” he lied, because he wanted it open. His eyes were bright in a way that made Doc feel like a floor had moved.

René ducked into the office for his bar, came back whistling “Be My Baby” because it made the pumps sound like backup singers. Doc stood with her palms on the top rail, feeling the remembered pressure of a mattress that wasn’t under her anymore. Somewhere in the pipes air knocked with a hollow clack. Peachy leaned on the mezzanine post and told them exactly what the demon inside a hollow gourd looks like when it finds a person to wear. He was trying to be funny. He wasn’t.

The doorjamb on the service entrance had been rotting itself to death for years. The county’s weld on the main door had forced everyone through this smaller weakness, and weakness is patient. René wedged the bar between the jamb and the brick and grinned. “Watch,” he said. “Five minutes.” He shouldered the leverage and pulled. The wood groaned. Nails remembered their obligations and then resigned. The jamb split clean along an old check like it had been waiting, tipped, and came away faster than physics had any right to allow.

Doc saw it happen from two places at once: from the rail where she stood, and from that small inch behind her own head where she often watched in the seconds after a blow. It swung, an ungainly door-sized limb, catching light from the high windows as if it meant to announce itself. She had time to think of course and then it hit her above the brow with the flat authority of a teacher’s book.

Sound went tall and thin, the way it does in the instant before it all rushes back. She sat without choosing to and let her body do the shaking it wanted. Peachy said “oh” in a small voice. René went pale and kept repeating “you okay, you okay,” like he was testing a microphone. Doc pressed her hand to the blood and felt more surprise than pain. She laughed once—the bark again—and said, “This is fitting,” because it was, because doors are how you leave and how people are kept out and how places declare whether you belong, and if a door wants to mark you then that’s between you and the door.

She let them fuss for a minute—Peachy tearing the hem off his shirt to make a bandage, René talking too fast about tetanus and responsibility—and then she stood. Her head swam and steadied. The pumps chanted like they’d never known any other weather than this. In the corner, the cracked gourd lay open like a mouth around nothing, and Peachy wouldn’t look at it. Behind René’s grin something dark had settled, as if the part of him that loved leverage had gotten exactly what it asked for.

They went outside because air felt like medicine. The marsh leaned under the sky. The smokestack wasn’t smoking—hadn’t smoked in years—but heat burped from the louvers and made the evening look like a film you could touch. René tossed the jack bar into the weeds and said, “Clubhouse is open,” and nobody cheered. Peachy sat on the concrete and stared at his hands like he expected them to move without him. Doc leaned her head back and let the blood find its way along her hairline, then wiped it away with the heel of her hand and watched it dry there like paint.

“This is where it goes,” she said, not to either of them. “The story.”

“What story?” René asked, uneasy because he preferred his stories delivered, not discovered.

“The one where the clubhouse ends,” she said. “Where everyone decides who they are without the pumps humming in their ears.”

Peachy nodded, eyes still on his palms. “I think I let something out,” he said, and tried to smile, and failed.

René kicked at the broken jamb and said, “We can fix it,” which was his way of asking to go back to being the kind of boy who could con a system into liking him.

Doc looked at the pumps and thought about the treehouse and the mountain and the window star and the thunder without storm, and about how the body keeps a ledger the brain can’t edit. She touched the knot rising under her skin and felt it taking its place alongside the others, a bead on a string that would one day have a name she wasn’t permitted yet to say.

“Maybe,” she said. “Maybe not.”

They walked home as if they’d been dismissed from something. René talked about how the county would never notice the door if they painted the edge. Peachy said nothing and held the empty gourd like a baby skull. Doc listened to the air. Somewhere out over the river a Chinook droned like a tired god, but it might have been only her memory looking for a frequency to settle on. The pumps kept time behind them until the marsh took the sound and made it weather.

When she reached her street she didn’t climb the sheet-rope. She went in by the front door and let it close softly on its hinges and stood in the hallway with her hand on the frame. The wood was cool. The sky outside was a deep, perfect bruise. Somewhere a storm would eventually decide whether to arrive. For the first time in a long time she didn’t try to leave her body. She kept it. She kept all of it.