Editor’s Note:

Again, we follow the children’s adventures through a landscape of Doc’s memories. This chapter explores the environs of the old Harris-Peaker landfill, which eventually became a Superfund site and a wanna-be Love Canal. Though the actions of the kids who played there were small, they attracted attention and may very well have led adults to do something about the problems there.

Chapter III: The Superfund Spring

Spring came everywhere except here. The air remembered how to be warm, and the birds tried their best, but the ground refused to play along. Even the light seemed reluctant to land on the place the kids called the Dump, as if it knew something about half-lives and guilt that they didn’t. Down along the old road, past the chain-link and the hand-painted NO DUMPING signs, the reeds still stood black as chimney brushes, and the mud smelled like hot pennies.

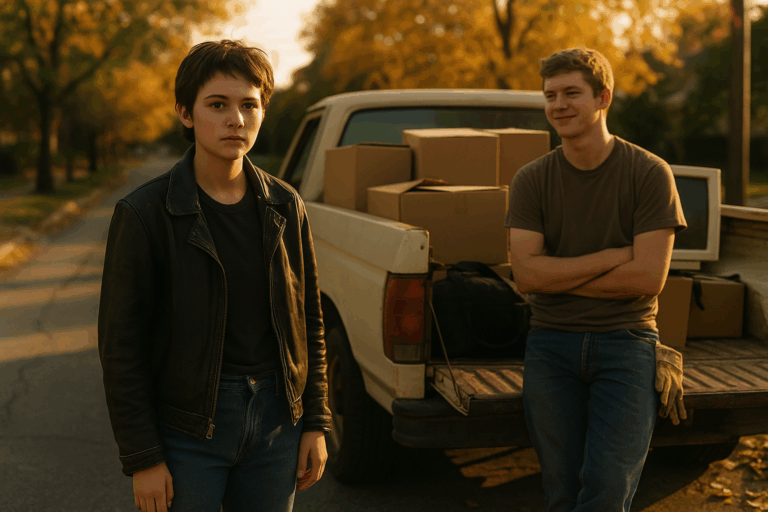

It was Peachy who found the house first, by accident, while chasing a half-rotten soccer ball the tide had coughed up. He came back hollering that he’d found a fort, a real one, with rooms and everything. Doc followed, skeptical until they saw it: a sagging two-story with horsehair plaster snowing out of the ceilings, its porch caved in like an exhausted lung. Somebody had spray-painted HQ on the front door in army green, probably a decade ago. The paint had bubbled and run, but the letters still looked official enough that they decided to keep the name. Headquarters. Home.

Inside, the air had that still, hollow quiet of a place long surrendered. The wallpaper had rotted into lace, and the floor was carpeted in a drift of paper—energy bills, grocery receipts, and letters from banks that no longer existed. Every step raised a tiny snowstorm of plaster dust, so of course they started throwing it at each other. It became an instant tradition: the spring snowball fight. The chunks of plaster broke in mid-air and rained down as a fine powder that made them all look ancient and ridiculous. René arrived halfway through, ducked a volley, and retaliated with the contents of a broken lampshade.

When they’d exhausted the ammunition, they explored. Upstairs, the walls had peeled in long gray curls. Peachy found an old diploma in a cracked frame, and when Doc wiped it clean with their sleeve, they saw the name—C. Milton Wright, the signature crisp and proud under a hundred years of dust. “Real history,” René said, and for a moment they all went quiet, as if the house might be listening.

Outside, the marshes were trying to bloom and failing. Shoots rose an inch and then withered to black. The cattails were the color of gun barrels. When the wind shifted, it brought a chemical sweetness that stung the eyes. Ducks still came to the pools, but their feathers looked oily, and they left perfect rings of rainbow when they dabbled. Peachy thought it beautiful. Doc didn’t.

René, of course, found a way to make it a stage. He plucked a long switch from one of the skeletal pines and began stripping its burned needles with a flourish. “Tree Strippers!” he announced in his best radio voice, “the only company that pays you to ruin your own foliage! Call now and we’ll throw in a free gallon of defoliant—‘cause who needs chlorophyll anyway?’”

Doc groaned, but they laughed. Peachy nearly doubled over, wheezing in the chemical air. René bowed, grinning. The humor was dark, absurd, teenage. None of them would realize for years how close it was to prophecy.

They made the place their base for most of that spring. The adults didn’t care; nobody cared about that patch of land. Sometimes, after rain, the ditches foamed white. Sometimes the puddles hissed like soda. They brought sandwiches and sat on the broken steps, daring each other to drink from the creek. When a gust of wind rattled the reeds, it sounded like a crowd whispering.

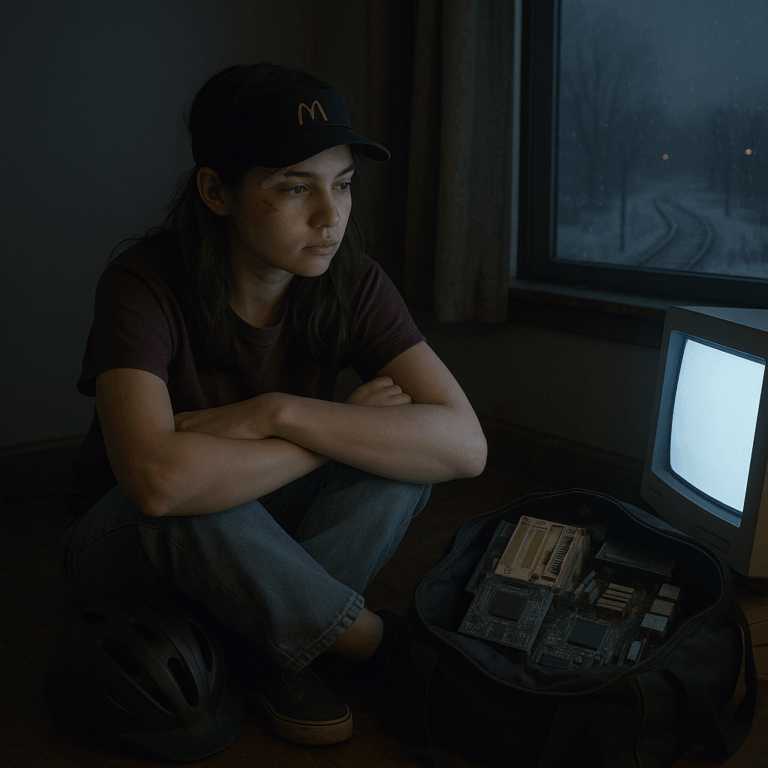

Doc started noticing small, wrong things. The rubber bands from Peachy’s braces—he’d always flick them around as ammunition—melted into sticky threads if they landed in the damp soil. A dead fish on the bank had no eyes. Even the gnats seemed sluggish, moving as though the air were thicker here. They began collecting samples in rinsed-out soda bottles, marking each one with masking tape. Water A. Water B. Water C. René teased them at first, calling them “Doctor Doom.” When they pointed out that his shoes were leaving black prints on the concrete, he stopped.

Back at school, Doc sweet-talked the lab assistant into letting them borrow some pH strips and a small centrifuge. They brought the bottles in their backpack, still half-full of the brown water. Under the fluorescent lights, the colors on the strips turned violent shades of orange and red—acidic enough to chew metal. The centrifuge leaked, and the smell followed them home. Their mother thought it was the drain.

They told René, of course. He’d been running his mouth all week about the next “HQ improvement project”—a roof tarp, a lookout post, maybe even an electric line spliced from a utility pole. He listened while they explained the readings, his brow furrowed in mock seriousness, and then broke into that crooked grin of his. “Perfect,” he said. “Free pest control. No mosquitoes at HQ—ever.”

“René, I’m serious,” Doc said. “It’s poison. That’s why nothing grows.”

He gestured grandly at the horizon. “The whole county’s poison, Doc. We just picked the spot that’s honest about it.”

Peachy, overhearing, added, “Hey, at least the ducks still like it.”

They didn’t know, not yet, that the ducks were dying downriver. That would come later, when headlines caught up with their games.

By May, HQ had become half clubhouse, half exhibit. They collected artifacts like archaeologists of the recent past: broken rotary phones, a cracked mirror, rusted paint cans with labels eaten away by time. The walls inside were a gallery of their finds. René even nailed up the C. Milton Wright diploma like a banner. “Proof,” he said, “that education leads to this.”

Sometimes he’d read the old bills aloud in a dramatic voice: ‘Dear Customer, failure to remit payment may result in discontinuation of service.’ He’d pause, look around at the shattered windows, and declare, “Guess they meant it.”

One afternoon, while they lounged on the porch steps eating peanut-butter crackers, a flock of ducks skimmed in low from the bay. They circled once, twice, then landed in the far pond with a sound like applause. Peachy clapped back. “Encore!”

But Doc frowned. The water under them was slick, filmed with a shifting rainbow. The ducks paddled through it, leaving black wakes. When one shook its wings, the spray came down in dark flecks that didn’t dissolve. Doc wanted to tell them to leave, to shout it, but their throat had gone dry. The wind brought the smell—sweet, metallic, almost floral. René sniffed and said, “Perfume for the end of the world.”

That was when Doc realized they’d been camping in the middle of the wound. The HQ house, the black reeds, the laughter—all of it built on ground that still whispered of barrels and leaks and the quiet, bureaucratic violence of neglect. They thought about the centrifuge, the burned rubber, the color the water turned on the strips. Peachy was throwing bits of plaster again, pretending to start another snowball fight. René was stripping bark from a sapling and humming some idiotic jingle. The world had turned the color of a bruise, and they were still playing.

That night, Doc couldn’t sleep. Every time they closed their eyes, they saw the black puddles reflecting the sky. In their dreams the puddles were mirrors, and in each one they saw their faces—their own, René’s, Peachy’s—dissolving like rubber bands in acid.

A week later they came back for what would be the last time. Spring had gone green everywhere else, but HQ looked unchanged: gray trees, black grass, the smell of ozone and something like vinegar. The diploma had blown off the wall and lay curled in a puddle, ink running. René picked it up and turned it over in his hands.

“Guess Mr. Wright’s not graduating again this year,” he said. His attempt at humor was thin; even he could feel it dying in the air.

They wandered without purpose, the way you do when a place has decided it’s done with you. René threw a stick at the pond and watched it hiss. Peachy lit a cigarette he’d stolen from his brother and blew smoke through the holes in the roof. Doc stood in the doorway, staring out toward the river, where the ducks had been.

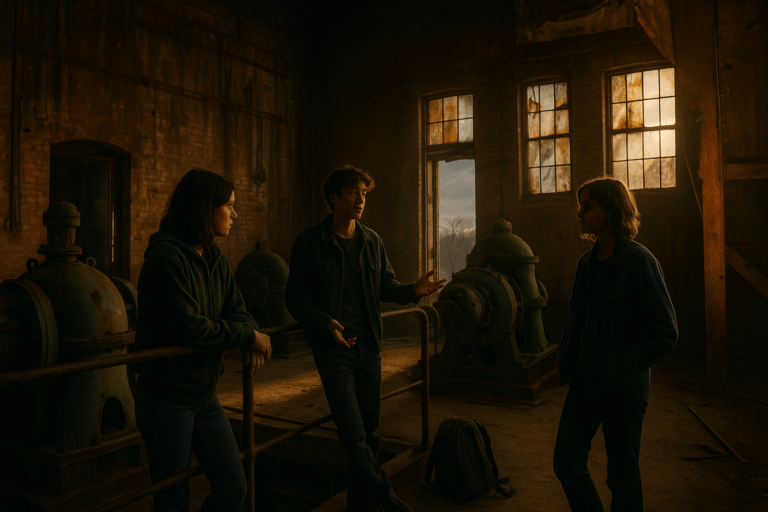

“Maybe we should tell somebody,” Doc said.

René laughed softly. “Tell who? The county? They already know. You think they put those signs up because they didn’t?”

He reached down, scooped a handful of blackened soil, and let it run through his fingers. “Look, the world’s full of poison. At least here it’s honest.”

Peachy shivered. “It’s still ours, though. HQ.”

Doc nodded, though they didn’t believe it. The house didn’t feel like theirs anymore. It felt like something they’d stolen, and the ground was about to take it back.

As they left, a single duck rose from the pond, flapping hard, its feathers streaked with iridescent black. It wheeled once, twice, then vanished into the bright air over the highway, heading north toward cleaner water. They watched until it became a dot.

No one spoke on the walk home. Peachy flicked his cigarette into the ditch. René said, almost to himself, “Tree Strippers’ll be out of business soon. Nothing left to strip.”

Doc didn’t answer. They were thinking about the bottles of dirty water hidden in their closet, the ones that hissed faintly when they opened one. They wondered what would happen if they poured some into the flowerbeds out front. Whether the flowers would grow or just turn black to match the rest of spring.