Editor’s Note:

We continue our story with a fusion of two different events that Doc remembers clearly, neither one of them feeling quite real anymore.

These events happened, though not the way they appear here and not at the same time. They’ve been changed. To the people whose names I left intact, I apologize. To the people whose names I changed, the same. To the facts we mangled deliberately, no apology necessary. It served the story.

Here’s how it begins — no hesitation, no coyness. Just the night as it was.

Chapter II: The Ice and the Sky

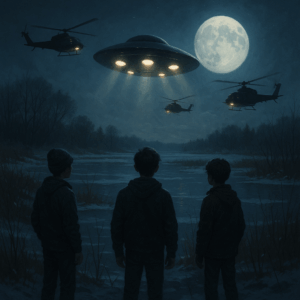

The night the river lit up, the air was so cold it made the world sound hollow.

Doc, René, and Peachy had followed the Bush upstream from the point, walking the frozen edge where the tide had pulled the water thin. The highway hummed far beyond the trees, a dull electric line between the houses and the proving ground. South and east of them—across the black channel where the river widened toward the bay—the Amtrak bridge crossed the river and Aberdeen’s floodlights painted the clouds a restless orange.

They moved single-file along the crusted snow, the way you do when you’re not sure where the ground ends. Every few steps René jabbed a stick through the ice and listened for the splash beneath. Peachy whistled tunelessly and said he liked how the marsh grass looked like burnt hair sticking up through glass.

Doc carried the flashlight, though they kept it off. Habit. The best way to see what didn’t belong was to let your eyes do their own work.

“Couldn’t pay me to live out here,” René muttered. “Whole place looks radioactive.”

“That’s ‘cause it probably is,” Peachy said, grinning. “You think they test their toys only on the base? Half that stuff blows this way when the wind changes.”

Doc didn’t answer. The Proving Ground had always been part of the backdrop—booms in the distance, searchlights now and then sweeping the treeline. Sometimes they tested artillery so heavy it shook the dishes at home. The grown-ups never looked up; they’d learned not to.

A gust rolled down the river, carrying diesel, salt, and the faint hum of transformers. Doc tilted their head. “Hear that?”

René stopped. “Another test?”

“No. Too steady. That’s turbines.”

They waited. The hum thickened into a vibration you could feel in the soles of your feet. A light bloomed low on the southern horizon—white first, then amber, then something between colors, as if the air couldn’t decide how to carry it.

Peachy whispered, “Chinook.”

“Maybe,” Doc said. “Except—listen.”

The beat was wrong. Too slow, then suddenly doubled. Another rotor joined in from higher up, a heavier chop. An Apache, maybe, flying escort. Normal enough—until the first light broke in two. The halves drifted apart, then back together again like magnets fighting a current.

René squinted. “That’s not refraction.”

“I didn’t say it was.” Doc retorted.

They crouched by a fallen log at the water’s edge, the ice creaking faintly beneath their boots. Across the river, a row of sodium lamps marked the perimeter fence of the proving ground. The lights beyond them weren’t lamps. They moved—slow, deliberate, and silent except for that low electric hum. Elliptical, almost vertical, like someone had taken a blimp and turned it on its side.

The machine glowed from the underside, a cone of light that fanned toward the river and stopped short of touching it. The air shimmered there, the way heat bends over asphalt in summer.

Peachy’s boot slid on the glare ice and he went down hard, skull knocking the crust with a sound that made René wince. Doc bent to haul him up by the elbows and muttered, “For once, it wasn’t me.”

Peachy held the back of his head and said, dizzily, “Doc, I think I hit my head pretty hard. I’m seeing lights.”

René chortled, “You must’ve hit it pretty damned hard, because I’m seeing them too.”

The joke should’ve snapped the tension; it didn’t.

There was a smear of meltwater on the ice where Peachy’s cap had skidded, thin as breath, and in that skin of wet the light from the southern sky drew a perfect oval like a coin pressed into frost.

“Hold still.” Doc touched the back of Peachy’s head, felt through wool for blood. Nothing. A knot would be there tomorrow, a pulsing little moon of its own. Peachy blinked, eyes watering from the hit, gaze caught past Doc’s shoulder.

“It’s lower,” he whispered.

René’s voice came from a crouch: “Two Apaches now. See the nacelles—no, don’t look at me, look at the profile when they bank. And there—Chinook, trailing. Running dark… why the hell are they running dark?”

The cold loaded the air with weight until sound traveled like pressure. The river held its breath. Downstream, near where the Bush opens its throat to the bay, a new circle of light descended and then—impossible—stayed there, suspended above the water as if the river had grown a second moon. No beacon blink, no red-green regulation. Just a white that wasn’t white, the kind of color you feel with your teeth.

Doc’s hands remembered Peachy and finished with him, but their eyes belonged to the machine. Elliptical, yes; they could see the curve now, the dark belly of a thing that should have had a name and didn’t. Four openings glowed under it, set in a cross, each casting a column downward that seemed to brighten the mist without quite reaching the ice. Where you expected reflection, there wasn’t one—only a soft, wrong gleam laid over the frozen skin of the river like silk.

“Not flares,” René said, too quickly, as if cutting the rumor before it could be born. “Flares fall. Those are holding.”

The helicopters swept in from the east like irritated insects. The Apaches came first, rotors chopping the air into violent geometry, searchlights licking the treeline and then shearing across the face of the UFO. Light scattered as if it had struck glass and been ground into dust. The Chinook followed fat and patient, twin rotors beating a rhythm you could feel through your boots. Every time the Chinook’s rotors aligned a certain way, Doc felt it in their ribs like an extra heartbeat.

The thing in the middle didn’t move so much as edit the sky around it. One second there, the next erased, then scribbled back a few degrees north, as if some operator above the clouds had dragged it along a timeline and let go. When it winked out, the helicopters didn’t lose their quarry—they surged toward the absence, blades whining, and the absence filled in again, smug and precise.

“Jesus,” Peachy said softly, not as a prayer. “I told you the water remembers.”

“The water’s not remembering anything,” René snapped, but there was no meanness in it; it was fear dressed as scold. “Aberdeen’s testing something. It’s gotta be. It’s… some kind of VTOL with—” He ran out of nouns and anger together. His breath fogged and disappeared.

Doc listened. They weren’t chasing explanations. They were counting. On, off, on—they tried to catch the interval. Seven seconds? Nine? No, irregular. A pattern that only held long enough to trick you into believing in it and then slid away. Their fingers, empty now, missed the flashlight the way a hand misses a railing. They didn’t raise it. You don’t point light at a thing you want to study in the dark.

A wash of air hit them broadside—no wind, exactly; more like the sensation of pressure reversing. The reeds bowed as if something vast had exhaled. The ice moaned beneath their boots, a long low note that rose into harmonics where the cracks made their own instruments. Peachy grabbed Doc’s sleeve instinctively. He would deny that later. Doc leaned forward a fraction, squinting to drag detail out of the dark.

The four lights under the craft were not fixed. Each brightened and dimmed out of sync, like lungs trying to agree on a rhythm. The cones of glow did a strange thing to distance: where they touched the haze, the world looked closer; where they didn’t, the night fell away into a pit. The craft slid sideways without yawing, keeping its face toward the river as if the water were the point.

René’s voice again, quieter now: “If that’s a lighter-than-air envelope, then where’s the—no envelope. No control surfaces. No heat signature. Nothing. How is there no heat?”

“There’s heat,” Doc said. “Smell it?” Ozone. Dry metal. The same bite that came on summer days when transformers blew after a storm, except finer, cleaner, like someone had polished the weather.

A floodlight lanced from the far shore—human, clumsy light with human intentions. It shot beneath the craft and struck the river, and for a second the illusion broke. The ice threw back what it was given, ordinary and flattened, reeds painted white at their tips. In that second the underside of the machine seemed to deepen, as if there were more under there than space: a throat, a cavity, a depth that didn’t match the outside. Then the human light wobbled, lost its hold, and the alien light—Doc refused the word, but only out loud—retook the night.

“René,” Peachy said, his voice shaking despite the brave weight he tried to give it, “if they tell us angels sang, are you gonna argue with them about pitch?”

“Angels don’t fly with escort,” René said. “They don’t need cover.”

Silence dropped so fast it made Doc’s ears ring. No rotors. No hum. No generator-thrum you could pretend was turbine pitch. The thing hadn’t winked out; it had gone dull, lights dimming to the color of pewter. In the full moon it became a shape instead of a miracle, and being merely a shape was somehow more frightening. The Apaches overshot, searchlights scribbling the wrong patch of sky. The Chinook yawed, corrected clumsily, circled.

Doc realized their heart was doing a hard, fast thing that didn’t match any of the machines. They felt the cold the way you feel a bruise you’ve been ignoring. The seams of their coat were sudden lines of pain. Their throat had that copper taste you get when you sprint. They swallowed and it didn’t change.

The craft—they refused the other words, but in their spine they said them—drifted toward the center of the channel, pause-sank a few feet, and then rose with the kind of steadiness that means indifference. The light-cones under it brightened again, sharp enough at their edges to make you want to run your finger along them to see if they’d cut you. A thread of fog tried to form and failed, shredded before it could cohere, as if each droplet had been told to make up its mind.

“Okay,” René said, as if negotiating. “Okay. Maybe it’s… optical. Maybe it’s a test of—of field projection. You can fake a lot of—”

The machine blinked, and in the place where it had been there was nothing. Not a shadow. Not a draft. The empty felt active, as if absence had weight. Doc heard Peachy suck air through his teeth. René’s gloved fingers clicked uselessly against his lighter.

When it came back, it was north and east, maybe a quarter mile, low enough now that the reeds beneath it twitched in the downwash. The Apaches converged fast, too fast, one banking hard so the moon slid across its cockpit glass in a smear. The Chinook lagged, hauled around by whatever inertia governs very heavy things that are asked to pretend otherwise.

“René,” Doc said, and he turned his head just enough that they knew he was listening. “If this were flares or balloons or some kind of trick, they’d be making a perimeter. They’re chasing. They don’t know what it’s going to do next.”

“Or they do,” he said stubbornly, and it sounded like he hoped he was lying.

Peachy started laughing, small and breathy, the sort of laugh a person makes when the only other option is to scream. Doc reached over without looking and squeezed his sleeve until the laughter stopped.

New sound, not from the sky this time: a staccato crack from far off, like someone snapping thick twigs in quick succession. Not gunfire. The ice. The pressure wave from the Chinook’s shift had finally reached their side and the river was answering. Cracks zipped under the skin, straight lines that met other lines and made maps. They all froze as if the ice could sense motion and punish it.

“Don’t run,” Doc said. “Weight low. Spread it out.” Their knees unlocked an inch at a time. They felt ridiculous giving orders to two boys they trusted more than they trusted most adults, and yet the orders were the only kind of prayer they knew.

They backed toward shore with an animal’s concentration, the marsh chewing at their ankles when they reached the reeds. Peachy breathed through his mouth, a white ribbon ghosting his lips. René never took his eyes off the sky even as his feet found frozen ground.

Another sweep of that wrong light turned the marsh gold and then silver, like an idea trying on outfits. The craft pivoted without pivoting, held there too long as if listening, and then slid toward the proving ground fence. For one beat—one impossible, treacherous beat—it passed in front of the full moon and became a silhouette, black and clean, oval as a coin you could spend. That was the moment Doc knew they would never talk her eyes out of their story. It had shape. It threw a shadow against a body that throws shadows on us. You don’t argue with that and stay honest.

The Apaches crossed in front of the moon in turn, ugly and beautiful, their rotor discs turning the night into a dealt deck of darkness and light. The Chinook trudged after, immense and faithful. From somewhere inland, a siren yelped once and then thought better of it.

“Enough,” René said suddenly. “Enough. We’re leaving.”

“Since when do you run?” Peachy said. His voice wasn’t challenging. It was grateful.

“Since I want to be able to say we left on purpose,” René answered, and that settled it.

They walked. No one looked away from the sky for more than a heartbeat, and even then their eyes snapped back like they were on elastic. The river sang its quiet, dangerous music at their backs. The marsh received them like an accomplice. The highway’s far electric hum reasserted itself as if it had never gone anywhere, as if the world had merely paused for courtesy and now resumed.

Halfway to Long Bar Harbor, Peachy said, “Do we tell anybody?”

René said, “We tell no one,” at the exact same time Doc said, “We tell each other.” They smiled without looking at one another, then let the smiles go. The cold had finally found their bones. It would live there for days.

By the time the lights of the neighborhood showed—a scatter of yellow squares made tame by distance—the night had calmed itself into something that could be survived. They cut through the dark fringe behind the houses, stepping over the places where kids hid their magazines and their shame. At the edge of Doc’s street they stopped under a bare-limbed maple and let the normal world cover them.

“In the morning,” René said, “it’s going to sound stupid.”

“In the morning,” Doc said, “it’s going to sound smaller.”

Peachy shrugged deeper into his coat. “In the morning, it won’t be night.”

They split there, each vanishing into a rectangle of heat and light that smelled like someone else’s life. Doc went up the steps with her keys already out, the metal suddenly heavy as a debt. Inside, the house was itself: the same pile of mail, the same glass on the counter, the same dull tick of a clock that had never agreed with their heartbeat. They stood by the window for a long time with the lights off and watched for the return of a thing that did not owe them anything.

For the next week, the story refused to choose a single shape. René insisted on a military test, then walked it back to “some weird optical array,” then to “a cluster of drones they’re not ready to admit.” Peachy said visitors without blushing and then, when Doc looked at him, clarified: not from heaven—just from somewhere else. Doc stuck to the only version they could live with: what they’d seen. An oval machine with four lights on its underside that moved in ways helicopters couldn’t, pursued by helicopters that did their angry, faithful best.

In the cafeteria, three different times, Doc opened their mouth to say it to someone who wasn’t them and closed it again. It wasn’t that they feared being mocked. It was that saying it aloud would make it smaller and they weren’t ready to be the one who shrank it. René told one person—a cousin who worked nights at the automotive place by the business park—and came back later furious that the cousin had nodded and said, “Yeah, flares.” Peachy told nobody, which for him was the loudest thing he’d done in years.

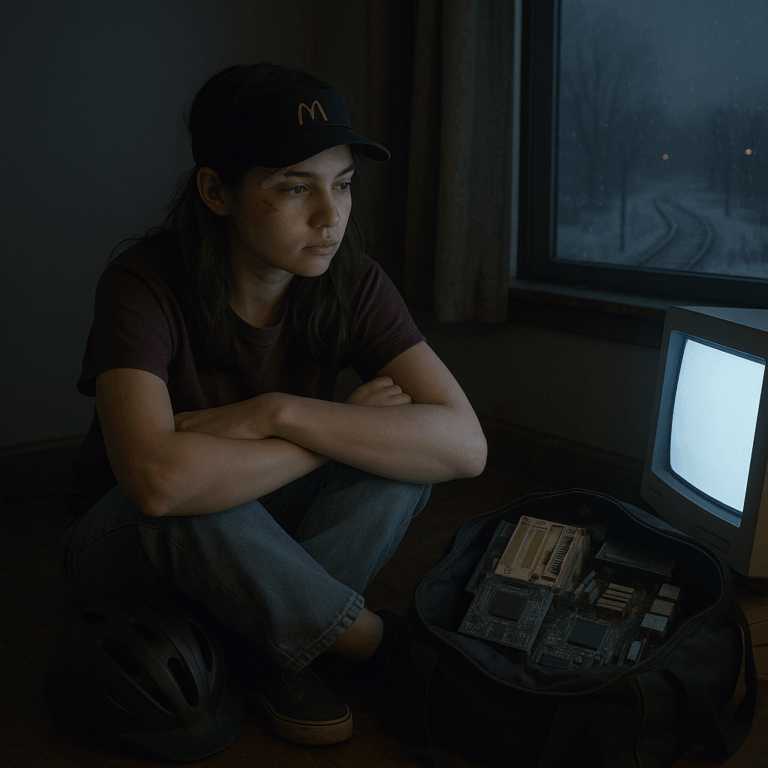

At night Doc woke to the memory of pressure changes, of air making space for something it couldn’t admit. They’d lie flat and count—on, off, on—and fail to catch a pattern. In shop class, when the belt sander whined up, they felt their ribs remember the Chinook. Out on the little truss bridge one afternoon, they pressed their ear to the tar-black wood and tried to separate the distant thunder of a freight car from the ghost of that generator hum. The body knows what it knows. It stores impossible nights in joints and cartilage and brings them back in weather.

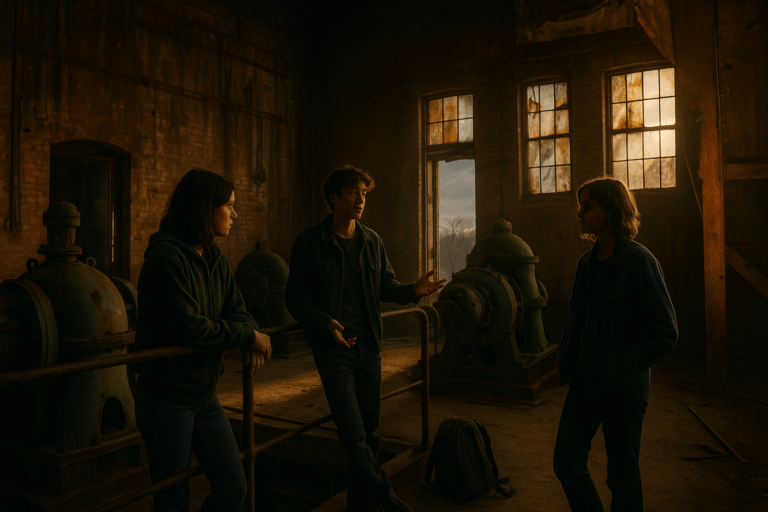

A week later, the three of them met by default at the convenience store, coins pooled for hot chocolate that tasted like paper and mercy. They took their cups to the edge of the parking lot and watched cars throw salt behind them. There was a silence that would have been comfortable any other week.

“Okay,” René said finally, as if beginning a meeting. “What did we see?”

“Machines,” Doc said.

“Visitors,” Peachy said.

René shook his head. “If we can’t agree on words, we can at least agree on facts. It flew. It held in place. It made light do wrong things. The Army chased it.”

Doc nodded. “And it made our bodies scared the way a cliff does.”

Peachy raised his paper cup. “To cliffs.”

René snorted, then lifted his cup too. Doc followed. They drank to the thing they could not share and to the private liturgies they’d built around it. After, they threw away the cups and said nothing to anyone.

Years later, each would tell a different story if forced, and each would insist they were not lying. They weren’t. Memory makes a library of identical books with different maps glued inside the covers. Doc never tried to pull René’s map loose or paste Peachy’s over it. They kept their own: four lights, an oval, a river that held still, and helicopters doing their best against a problem they hadn’t invented.

And if sometimes, on windless nights when the marsh went glassy and the moon fattened too fast, they felt the world tilt around an absence they could not name, they didn’t tell anyone that either. Some truths don’t need belief. They only need a witness.