Editor’s Note:

This is a story that I jokingly called “‘Stand by Me’ meets ‘Stand by You'”. It is a memoir of our formative teenage years, and also a testament to the resilience of children — people who grow up at some point and eventually become adults who have to clean up the messes left by generations who came before them.

To ‘Sir’ Mr. Richard Gallagher: if you’re even out there, you are most likely dead anyway, so who really cares now? I just want you to know that I did in fact grow-the-fuck-up and, no, it didn’t help.

Chapter I: The River Children

Doc learned the shape of danger by listening for it. That was the first lesson, learned young enough that it fused with the bones: the way a far sound arrives before the thing that makes it, the way vibration lets you know what the eye won’t admit yet. He and Peachy lay flat beneath the little truss over the Bush River, faces pressed to the splintered crossbeams, and let the world announce itself in tremor. The ties above them were old, tar-seeped, freckled with coal, littered with rusted spikes hammered flush by a century of weight. Through the slats, Doc could see a ribbon of sky, thin as a paper cut. The cold steel kissed his cheek with the taste of old rain.

“It’ll come,” Peachy said, but it was half dare, half prayer.

Doc just nodded. He didn’t have to say it: he could already feel the earliest hint of thunder. Not a sound yet, a feeling, low and wide and patient, as if the river itself had rolled over in its sleep. He imagined the train far downline—heavy boxcars, maybe a flatbed with a bulldozer chained to its spine—leaning into the turn that would shiver the world all the way out here. The breath in his chest turned thin. He kept his ear to the wood, the cold and the creosote burning his skin a little, and let that thinness sharpen him.

When it came, it was everything. The engine hit the trestle like a hand slamming a door that wouldn’t shut. The rails screamed and the ties shook and the little bridge became a drum their faces were pressed against. Peachy flinched and swore and laughed all at once. Doc didn’t laugh. He shook, and his stomach did a strange hollow thing, and he clung to the notion that if he just didn’t move then all of this would pass through him instead of knocking him loose. Above, the bellies of the cars rumbled like iron weather. Wind shoved at their hair. Grit fell in small avalanches, flecking Doc’s eyelashes with black salt.

After, there was a silence that rang. The freight groaned itself downriver, diminishing into a tail of clanks. Peachy rolled onto his back and stared up at the winter blue through the lattice of steel.

“Jesus,” he said. “Let’s do that again!”

Doc wiped at his eyes, left a gray smear across his brow, and said nothing. The trembling inside him hadn’t decided whether it was fear or joy.

They lived in a place that demanded both. The Bush moved slow and brown when the tide swallowed it, then showed its ribs when the water slipped away and left the marsh to steam and whisper. In summer the grasses were a green wall full of insect gossip and secrets. In winter, the whole thing went hard. Boots could step where minnows swarmed in August. The marsh gave up its passages, the thin ice spider-webbing between hummocks of peat, and the kids marched through it like conquistadors trying not to fall into the very country they claimed. Doc liked winter best for that reason. Boundaries were visible. Risks wore a crust he could test with a boot heel. The cold made the air unambiguous.

They crossed the little bridge often enough that it stopped being a dare and became a road. Across the tracks there was Riverside, which was not a river and not a side but a development pretending to be both. The houses sprouted all at once from clay like teeth in a young mouth, the lawns shaved and scabbed. Doc liked to walk those streets at dusk when the living rooms lit up, each big square window a television pulled from a catalog. You could see families arranged like furniture. A father with a beer. A mother at a sink. The blue glow of a screen sifting across the carpet. He felt like a ghost, separate from all that warmth, but not unwelcome. Just unclaimed.

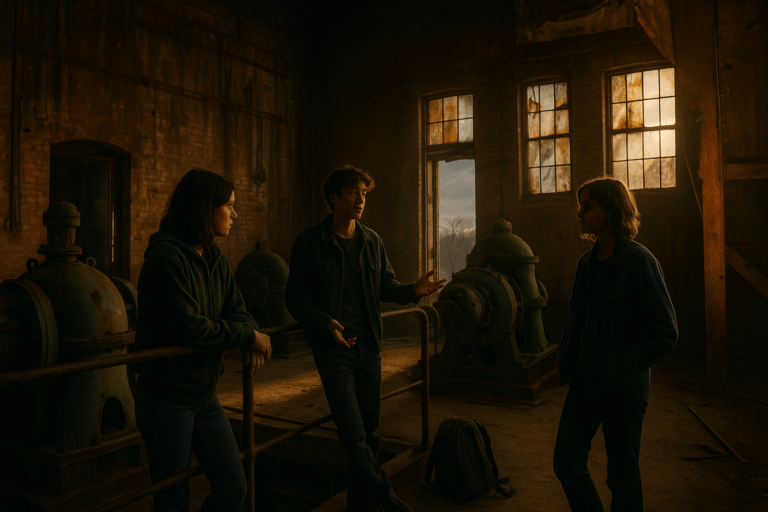

Beyond Riverside stood the hulking carcass of the Beta Shoe Factory, a century of labor petrified into brick and soot. It carried its own weather—dead air, cool even in July, that smelled like leather gone to sleep. Attached to it were its appendages: a parking garage whose yawning mouths swallowed light; an abandoned hotel with tall windows like blind eyes; the row of slave houses behind, little brick tombs that held heat like a confession. The adults called them “quarters,” as if a smaller word could reduce the sin. Doc walked that row with his hands behind his back, the way he’d seen old men do at graveyards, and imagined the life inside each cubicle—tired backs, hands held wrong around a plate, a prayer with no object. He didn’t have the words yet for the rage it made. He only knew the brick remembered what people tried to forget.

The marsh was the children’s commons, where the rules shifted and the lessons cost you blood if you weren’t careful. In winter, the kids moved through it in a band: Doc and Peachy, Lolo with his scarf wrapped three times and still sneezing, René who could run on the tips of hummocks like a fox, and sometimes Leah, who would show up in a coat too thin and refuse any help with her chin high. Ice made everything navigable. They learned to read it the way they had learned to read the rails: by the pitch it sang when they tapped it with a stick, by the way it went cloudy under a cautious boot, by the quicksilver flick beneath. Doc taught himself to listen for depth the way he listened for trains. He would kneel and lay a palm flat to feel what stories cold water told.

Out there, the world was full of relics. Rusted barrels the reeds had decided to mother. Tires half-buried in peat, each a black moon. A length of chain ending in nothing. They found a deer skull once that January, teeth neat as a string of pearls, the sockets cleaned by time to perfect ovals. Doc lifted it gently and felt the balance of a head with nothing in it, the way the world got lighter when the thinking parts were taken out. He set it back. Lolo said they should take it to school and freak out Mr. Reaves the science teacher. René said that was stupid and left it where the flies would find it in spring. Doc thought about putting it on his wall the way the Beta Factory wore its town like a pelt. He left it too.

The other bridge—the long one, the one over the Gunpowder—was a different sermon entirely. It didn’t ask for listening so much as faith. The tracks ran into a sweeping curve so that once you stepped onto the first tie you committed to a part of the air where you could no longer see what might be coming. The rails and the ties were canted on the angle to ease some invisible physics Doc only half understood, which meant your feet learned a crooked way of walking, a little tilt that suggested the ground might not always be under you. Far below, the river scissored itself into white where it hit rock. Thirty, maybe fifty feet of space between the last good decision and a neck broken clean.

Still, they crossed it. Of course they did. Children keep the covenants adults break. They were quiet there, each measuring risk in the private math they built from mothers’ warnings and fathers’ shrugs. Doc’s math was two parts hypervigilance and one part fondness for the sensation of existence sharpened to a point. He didn’t trust a dodge. He didn’t plan to jump, not ever. Down there the river showed its knives, and besides, at low tide he’d seen the old wooden pilings stand up out of the water like the ribs of a prehistoric thing, black and pointed, set exactly where you’d pray to land. He kept his ears tuned, his eyes on the back of Peachy’s jacket, his hands loose and ready to go still.

They could have gone the long way around, down to the convenience store and the post office that were technically on a highway but felt like a porch where America stopped to think. The store’s sign promised everything—ICE, BAIT, LOTTO—and delivered only the kind of sugar that put a film on your teeth. Doc liked the sound of the cooler doors when they sucked themselves shut with a breathy thump. He liked the way the post office smelled like ink and dust, and the way Mrs. Beale behind the window could find a package without looking. He bought a stamp once just to keep it, the little flag miniature that made the country feel like a picture you could lick.

Past that sat a business park so ordinary it made him suspicious. Square buildings with names that promised magic: a microwave research company whose glass doors held his warped reflection; a factory that made the oil that made Skittles taste like Skittles, which felt like a kind of alchemy too humble to brag about; a BMW place with a ladder that ran thirty feet up the side to where the steel roof made a platform above the world. He and René would climb it at night—the first time shaking, the second time laughing—then sit with their legs dangling over the lip and count the stars, which were never as many as the pictures promised, but were honest about it. The cars on the highway moved like fish slipping a net. The river lay dark and thinking. In that perch Doc felt an architecture he couldn’t name settling into him: a sense that he would someday build a thing that could hold a life through winter.

He didn’t think of gender on those nights so much as he wore it like someone else’s coat—serviceable, too big in the shoulders, sleeves you could roll up. He behaved like the girls he loved—careful, tender with detail—then argued with himself that the words for that weren’t permitted where he lived. He accepted “he” the way he accepted the winter ice: not what he wanted, but something you could cross if you learned its song. Peachy didn’t mind. René didn’t mind, either. They called him Doc because the name was a joke that stuck, born of an afternoon with a broken transistor radio, a cheese-box, and a small triumph. The nickname fit in ways other names didn’t; it suggested the person he might someday get to be—someone allowed to fix and keep and mend.

They trespassed everywhere because childhood was a passport. The quarry sat like a pupil in the eye of a scar of land, a wide circle of water that had long since given up pretending to be useful. The old man who lived nearby hated them. He hated them extra because they were white and because they were children and because he understood that both things carried a sense of entitlement and invincibility that the quarry would correct without mercy. He came out of his little house with a switch in hand and language that snapped like the branch it came from.

“Get,” he’d shout, and his voice carried over water the way anger does. “Ain’t nobody coming to fish you out when you fall in. Not me. Not the Lord. Get.”

He’d say worse, too—things about smacking the white off them and making them honest black before they were allowed to come back. The first time, Doc went hot with shame and confusion, wanting to tell the man he already knew about not being the thing people took him for, wanting to ask whether that meant he could stay. He didn’t. He climbed the chain-link, tore his coat sleeve, and ran with Peachy, who hollered back something obscene that got swallowed by the open space.

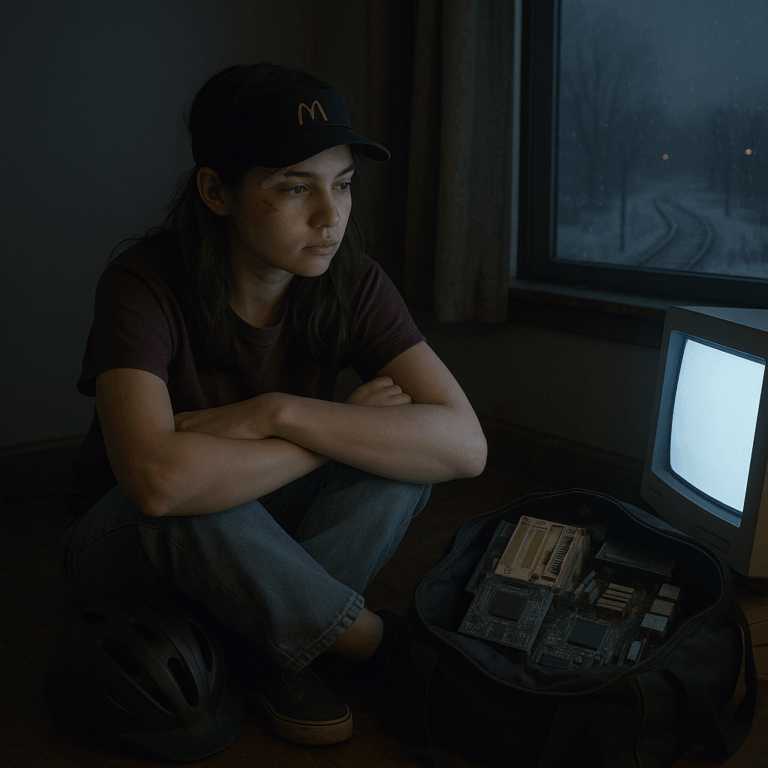

On another day, Doc came alone, skirting the man’s house by going long through the reeds and dropping to his belly when a flock of geese rose as if pulled by a string. The quarry was gray that afternoon, a flat coin under a low sky. He sat on the rim with the stolen dosimeter in his lap, a clunky thing he wasn’t supposed to know how to use. He didn’t understand its numbers, not really, but he loved the way it gave shape to the invisible. He’d click it on and wave it around like a divining rod, half-hoping it would find a terror he could solve. He wasn’t stupid. He knew the apocalypse wouldn’t look like the movies had promised. It wouldn’t be clean white flash and mushroom. It would be a hundred smaller humiliations, each needing a plan.

He planned. He imagined pumps big enough to empty the quarry—he’d seen their cousins at the pumping station over by the water treatment plant, fat green cylinders with a hum like a sedated animal. He pictured moving them here with a truck he couldn’t drive yet, powering them with a generator he would teach himself to coax awake, lowering the hoses into the quarry’s throat and letting the water go where it wanted to go. He drafted a lid in his head, a concrete cap to keep the world’s fallout from drifting down. Inside: shelves, miles of them. Not just books but maps, seeds, microfilm full of deliciously tiny answers, and metal cabinets with drawers that locked. He would climb the thirty-foot ladder to the BMW roof at night and sketch it in his notebook by sodium light. He would stop at the post office and buy a single stamp and paste it on the first page, as if to say: we will mail ourselves into the future.

René laughed when Doc told him. “You’re gonna save Skittles and cars and microwaves?” he said, but it wasn’t a mean laugh. “What about people?”

“They’ll save themselves,” Doc said, more bravado than belief. “We can keep the instructions.”

On afternoons when the tide sank and the marsh exhaled, he’d walk home over the little truss with his collar up and his ears straining. He could hear things others didn’t, or so he told himself: the ball-bearing rattle in a distant shopping cart, the first plop of a muskrat into black water, the whisper of a train so far off even Peachy said he was making it up. He wasn’t. He believed in distant signals. He believed that if you learned to hear what was coming long before it arrived you could choose something other than panic.

Still, panic had its vote. There were days he misjudged. The winter ice on the marsh could surprise you. It did not care how careful you were, only how lucky. Once, following René’s quick steps, he put a foot down where the skim looked firm and it went spiderweb in a single breath. He had time to say “oh” and then he was in up to mid-thigh, cold knifing at his femurs. The fear was so pure it made his head feel too big for his body. He flailed and found a tuft of grass and rolled his weight onto it, panting. René reached a stick out and didn’t make a joke until he was safe, which was his version of kindness.

“You’re gonna get yourself killed,” Peachy told him that evening, but it wasn’t an accusation. It was a statement of weather, like saying snow might come. Doc shrugged and said, “Not today.”

He kept a reckoning of head wounds in a private ledger. There had been the time under the Beta Factory when a loose pipe, swung thoughtlessly by Lolo, clipped him at the temple and put him down on one knee with a strobe of white behind his eyes. There had been the winter where he miscalculated the distance between two crossbeams under the little bridge and smacked his crown hard enough to make his teeth sing. There was the night on the BMW roof when he stood too quickly from the edge and cracked the back of his skull on a pipe that hadn’t been there the previous week. Each blow taught him something unkind about the world and something honest about himself: that his skull was not a symbol, just a box; that inside it was a delicate meat that nonetheless kept making meaning even when you shook it; that seeing stars had nothing to do with astronomy and everything to do with a private sky.

After one particularly stupid collision—running in the dark on the Riverside sidewalks, chasing René’s dare to jump and tag the stop sign and sprint home, and missing the overhanging maple limb by exactly the thickness of his awareness—he sat on the curb with his hands on his thighs and waited for the nausea to ebb. The stars above Riverside were few, the houses too bright, but they arranged themselves into a shape he would later call resolve. He didn’t have the word then. He had the sensation of a decision beginning.

When they needed money for candy or for a nail they could bend into a fishhook, they scoured the post office parking lot for dropped change, ran the business park’s edges for bottles, or went to the convenience store to ask if Mr. Jaffar needed the ice freezer chipped clear. He always did. He handed them a dented scoop and a bucket and told them not to break their wrists on it. Doc liked the resistance in the work—the way the ice grudgingly released what it had stolen from air. He pretended sometimes that each chunk he freed was a dangerous idea he was extracting for later.

It wasn’t all hazard. There were Saturdays made of nothing but sun and the sound of swing-sets groaning and a baseball hitting a thin aluminum bat. There were nights on the BMW roof when the sky admitted more stars than usual and the cold made everything feel earnest. There were afternoons in the abandoned hotel where light came in like something holy and made the dust look like it mattered. Doc would stand in that light and think about bodies in a future he could not picture yet, about the names he didn’t have permission to use, about the difference between being seen and being understood. He didn’t think the word girl. He didn’t think the word boy. He thought about clothing that fit like the right idea, about a voice he would eventually grow into like a pair of boots.

He cataloged the town—not to possess it, but the way one memorizes evacuation routes. Beta, Riverside, the quarry, the little truss, the long curve over the Gunpowder, the ladder, the roof, the post office, the Skittles oil place whose proper name he refused to memorize because the truth of it was better. He knew where the ground went soft, where the rails sang earliest, where the old man’s eyes could find you if you came too close to his grief. He knew which reeds could cut you and which could be woven into a crown you’d take off before any adults saw you. He knew the exact number of ties between the first safe beam on the long bridge and the point where you had to commit to the middle, where standing still felt like an act of faith and moving felt like a dare. He taught his body the habit of stillness. He learned that sometimes the right answer to an oncoming thing was to lie down, grip the world, and let it pass through.

On the night he and René climbed to the roof and the cold made the steel sing under their boots, they lay back side by side with their arms out like angels who had lost their instructions. Doc watched his breath and thought about the underground library he would cut into the quarry’s throat with pumps he’d steal from the pumping station. He thought about the future apocalypse, the one that would not be the one everyone practiced for. He thought about a life with agency, the day when no permission would be required for a name to match a shape. It felt impossible in the way that buildings feel impossible before someone draws the first straight line.

“You’re quiet,” René said.

Doc considered lying, then didn’t. “I’m listening,” he said.

“To what?”

“Everything that’s too far off to see yet.”

René turned his head. “Can you hear it now?”

Doc nodded. Maybe it was only the hum of the business park at idle, the river rubbing itself against stone, the highway letting out a long tired breath. Maybe it was the planet, turning. Maybe it was the sound of a person beginning, which is quiet enough most days that you have to press your face right up against the bones of the world and wait for it to arrive. He didn’t know which. He only knew the feeling: a low, patient thunder, a promise with no specifics, a train so distant you could deny it if you wanted to.

He didn’t deny it. He lay there with the cold stealing into the back of his coat and the stars admitting, for once, that they might be infinite after all, and he practiced holding still.