Annotated commentary of contemporaneous analysis regarding political and random violence in America during the period of 2020 to 2050.

Author’s Disclaimer (c. 2060 Edition)

Readers should be aware that the following account does not always align cleanly with the historical record as we remember it. Scholars generally divide into three schools of interpretation:

- The Suppression Hypothesis — These events did occur, but evidence was deliberately buried, misreported, or obscured at the time by governments and media institutions.

- The Alternate Timeline Hypothesis — The document originates from a branch of history that diverged from our own, preserved here through means unknown. In this view, its contradictions are features of some quantum timeline we narrowly avoided.

- The Hoax Hypothesis — The work is a deliberate fabrication, either satirical or propagandistic, but valuable nonetheless as a window into the anxieties and expectations of its era.

Which of these is correct remains unsettled. What follows should therefore be read as both history and cautionary fable.

Editor’s Foreword (2060 Edition)

The text you are about to read occupies an uncertain place in the archives of American history. On its face, it is a sequence of case studies describing the political and cultural violence of the early twenty-first century. Yet in its details it often conflicts with the timelines we recall, introducing events that some say never occurred, while omitting others that surely did.

This has not prevented its study. If anything, the contradictions have only sharpened its value. For more than three decades, scholars have argued over whether the document is:

- a suppressed record of incidents deliberately erased from public memory,

- a relic from an alternate timeline, preserved through some quirk of transmission, or

- a hoax — albeit a hoax so insightful that it captured the very texture of an age.

That texture is undeniable. Even when its particulars diverge from the consensus record, the document captures something essential: the way violence was consumed as performance, the way symbols outlived bodies, the way uncertainty itself became part of the spectacle.

For these reasons, the work is best approached not as settled history but as cautionary literature. It warns, even in its errors, what a nation may become when tragedy is interpreted more eagerly than it is mourned.

Readers are invited to judge for themselves which school of interpretation they find most persuasive. The editors merely note that truth and fable are not so easily disentangled in this era — nor, perhaps, in any other.

— A. Reynolds, Ph.D.

Chair of Violence Studies, Columbia University

Revised Edition, 2060

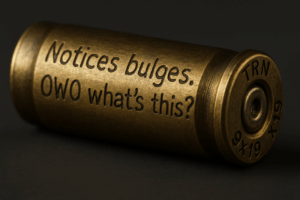

The Bullet That Wasn’t

On the morning of September 12, 2025, staff at the Utah County Sheriff’s evidence room began the meticulous work of photographing each casing left behind by Tyler Robinson’s rifle. They were looking for fingerprints, striations, tool marks — anything that might tell a story. What they didn’t expect was to stumble onto a single word that would write its own.

Stamped on the brass rim of one casing, between “OWO” and “Bella Ciao,” were three letters: TRN.

The first analyst assumed it was a machinist’s mark. The second thought perhaps it was shorthand for training. The third — a junior stringer for the Wall Street Journal — saw something else.

By that evening, a bold headline appeared above the fold:

“Shooter’s Casings Show Pro-Trans Messaging.”

Within hours, the story metastasized. Right-wing talk shows replayed the graphic, arguing that trans activists had “blood on their hands.” Progressive commentators countered with their own misread: perhaps “TRN” was Robinson’s sly admission that the trans community was blamed unfairly. The letters themselves — plain, blocky, anonymous — became a battlefield.

The Correction

Seventeen hours later, the WSJ issued a correction. The casing, they admitted, had nothing to do with trans activists. “TRN,” it turned out, was a truncated part number: TRN-500, a manufacturer’s shorthand used on certain lots of brass produced in Kentucky.

But by then, the correction was irrelevant. TRN had already left the evidence room and entered the bloodstream of culture.

Arms and Memes

In LGBTQ forums, users began posting range selfies tagged #TRN. A viral Discord server called itself The TRN Line Defense. On Etsy, enamel pins appeared: a bullet casing wrapped in rainbow stripes, the letters stamped proudly across the rim.

One user summed it up succinctly: “If they’re going to blame us anyway, we may as well deserve it.”

Meanwhile, in far-right spaces, the same letters were co-opted in opposite form. Memes reframed TRN as shorthand for “Trans Radical Negligence.” Some circulated faked images of casings bearing the letters as proof of conspiracy. The phrase soon appeared spray-painted on synagogue walls in Ohio, woven into slogans of militias in Idaho, and scrawled on bathroom stalls in Florida high schools.

By the spring of 2026, the same three letters had become both a badge of solidarity and a mark of suspicion.

The Semiotics of a Mistake

Here’s the irony: had the casing never been misinterpreted, it would have joined thousands of other anonymous shells, forgotten in an evidence drawer. But with a single sloppy headline, “TRN” became a cipher for a decade’s worth of paranoia, resistance, and propaganda.

Like graffiti on the walls of Pompeii, it survived not because it meant something, but because people decided it must mean something.

Footnotes

- The “TRN Panic,” as it came to be known, illustrates how symbolic violence can metastasize faster than physical violence. While Robinson killed a man, the TRN sigil radicalized thousands.

- Estimates vary, but historians now believe LGBTQ firearm ownership quadrupled between 2025 and 2027. Gun shops reported “rainbow Fridays” when entire stockpiles of pistols were purchased by queer collectives, often for ceremonial display rather than practice.

- Coalitions formed in those years were notoriously fragile. Disabled veterans, queer activists, and neurodivergent youth often clashed on strategy. Yet for a brief moment, “TRN” provided the first unifying rallying cry.

- Curiously, “TRN” was later absorbed into commercial culture. A pop-punk band released an album titled Catch TRN!; a breakfast cereal ran an ad campaign featuring neon casings with the letters embossed. By 2050, the majority of consumers no longer associated the sigil with its bloody origins.

- The original casing is still on display at the National Museum of Violence in Washington, D.C. The placard notes simply: “Engraving misread by press; subsequent cultural significance exaggerated.” Tourists photograph it more than the nearby JFK rifle.

Closing Thought

It was, in the end, a machinist’s mark. Yet in the volatile atmosphere of 2025, a machinist’s mark could move markets, arm militias, and create its own history. That specific bullet casing had not killed anyone — but the story that grew from it changed the course of violence in America.

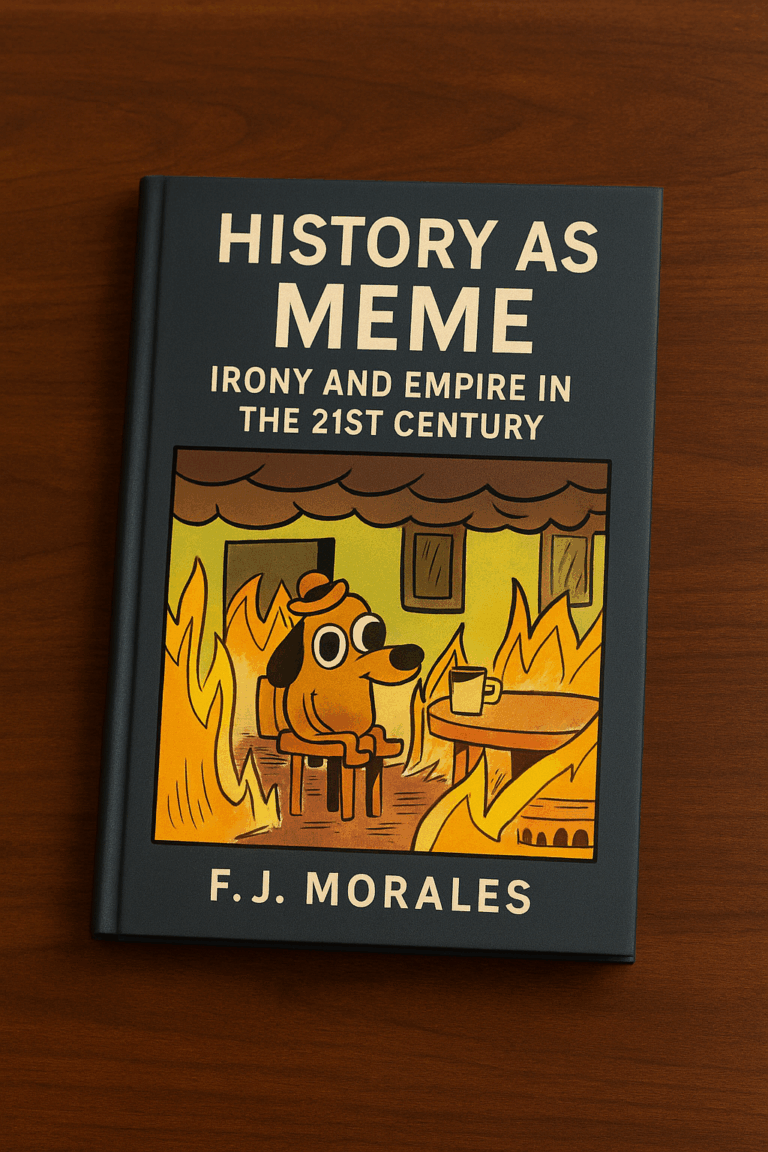

The Meme as Weapon

When the rifle cracked in Utah Valley, it was not just a bullet that left the chamber. It was a joke.

The first casing recovered bore the phrase: “Notices bulges. OWO what’s this?”

On Discord servers and image boards, the line was already infamous — a parody pickup line from the depths of furry forums, resurrected as ironic shorthand for awkward lust. In text it was absurd, embarrassing, designed to make its audience cringe. Spoken aloud it sounded like something no one would ever say in earnest.

And yet, engraved in brass, it became lethal.

The Collapse of Irony

Observers noticed immediately that this was the casing of the first shot. The shot that struck true. Commentators online quipped darkly: “The OWO bullet never misses.” Others framed it as an omen: the most absurd meme carrying the deadliest consequence.

What had once been ironic roleplay was suddenly deadly serious. The absurdity and the violence did not cancel each other out — they fused.

Performing for the Invisible Audience

Robinson could not have expected his victims to understand the joke. The engraving was not meant for them. It was meant for everyone else.

For the thousands who would later pore over crime-scene photographs, repost the images, crop them into avatars, stencil them on protest signs. In this way, the bullet was not only a weapon — it was a performance, a message staged for an invisible audience who would discover it after the fact.

The casing was a tweet made of brass, a meme fired at supersonic speed.

The Meme’s Afterlife

Within days, the line had been reproduced on stickers, graffiti, and tattoos. A queer punk collective in Portland spray-painted it across the police precinct wall. An anti-fascist zine in Berlin used it as a cover headline. By 2027, an energy drink called OWO Shot was selling in convenience stores, its slogan: “Lethal Energy.”

What had begun as a joke, and then became a killing, now returned once again as a joke. The circle was complete.

Footnotes

- Scholars now cite the “OWO Bullet” as the first clear instance of meme semiotics weaponized in live fire. Earlier incidents — shooters livestreaming on Twitch, or posting manifestos on 8chan — were performative, but the bullet itself was not inscribed. Robinson collapsed those layers.

- Later research shows the engraving had no measurable effect on Robinson’s accuracy. The deadliness of the first shot was coincidence, though mythologized as fate. The phrase “OWO never misses” persists in online slang to this day, usually as a sarcastic reply to correct predictions.

- Commercial appropriation of the meme far outpaced its political use. By the mid-2030s, the majority of Americans under thirty associated the phrase with energy drinks, esports, or adult animation rather than with Robinson’s act.

- The irony of irony becoming literal has been noted by cultural theorists. The meme began as a parody of desire, became the tool of a killing, and then was parodied again. Baudrillard might have called it “murder by simulacrum.”

Closing Thought

The OWO casing shows how humor and horror can be etched into the same metal. A bullet can be both a joke and a death sentence, and the distance between them is only the width of a trigger pull.

Luigi at the Con

In the summer of 2027, at a mid-sized anime convention in Denver, a man in a green cap walked into the dealer’s hall carrying what looked very much like an assault rifle.

He was not the first to do so.

For an additional three years or more after Utah Valley, Luigi with a gun remained a recurring figure at fandom gatherings. Sometimes the rifle was real, more often it was airsoft. Sometimes the man was lanky and quiet, other times short and cheerful. Sometimes there were two or more Luigis in the same weekend, as if the role were franchised.

It became impossible to tell whether it was the same person making the circuit, or dozens of imitators.

The Archetype, Not the Man

“Luigi” was never formally identified. Convention staff banned a few attendees, police questioned others, but the character remained slippery, an archetype rather than an individual.

Cosplayers compared notes: he always posed for photos, never broke character, and sometimes gave out empty brass casings stamped with memes — “Catch, Fascist!” or “Game Over.”

What frightened officials was that he never crossed the line into actual violence. There was no arrestable offense in dressing as a Nintendo plumber and holding a prop gun. Yet the anxiety was palpable: parents pulled children from photo lines, dealers kept eyes on their exits, and security reports tripled every time Luigi appeared.

The “Luigi Effect”

Sociologists coined the term Luigi Effect to describe the phenomenon: a character who could be simultaneously beloved and menacing, welcomed into selfies yet whispered about as a potential killer.

The Luigi Effect wasn’t about a single person — it was about how the specter of violence could travel on a costume, a color scheme, a stance.

By 2030, Luigi had become a shorthand in risk management: a “Luigi” was any ambiguous presence at a public gathering that might tip harmlessly into catastrophe. A lone protester with a megaphone. A gamer with a backpack left unattended. A masked figure loitering near the Metro.

The Return to Fandom

Ironically, Luigi’s endurance was less about politics than about fandom itself. Attendees liked the frisson of danger, the feeling that they were part of a meme bigger than themselves. “I got my photo with Luigi!” became a bragging right, like shaking hands with a celebrity.

On TikTok, montages set to EDM beats showed Luigi waving at the camera, kneeling dramatically with his rifle, or sitting cross-legged in the food court. Captions: “He didn’t shoot me lol.”

It was cosplay as performance art, satire as survival exercise.

Footnotes

- The Luigi archetype is now considered a “floating signifier of menace.” Scholars compare it to earlier cultural bogeymen like the clown panic of 2016, or the masked anarchists of Occupy. Unlike those, however, Luigi remained playable — audiences could embrace or reject him depending on mood.

- Police records from 2027–2029 show at least 43 separate individuals cosplayed Luigi-with-gun across 19 states. No two descriptions matched perfectly. The ambiguity only strengthened the archetype.

- By the late 2030s, “Luigi” was absorbed into performance art. A troupe in New York staged The Green Man With Gun, a dance piece exploring the boundary between theater and terrorism. Critics praised it as “the cosplay Hamlet.”

- The meme’s eventual decline is usually dated to 2041, when Nintendo filed a lawsuit against a weapons manufacturer selling green-plated rifles under the brand “Super Brother Defense.” Once Luigi became litigious IP rather than cultural archetype, his menace diminished.

Closing Thought

Luigi at the con was never about violence committed, but about violence imagined. He stood at the liminal edge of play and terror, proving that sometimes the scariest figure in the room is the one who never pulls the trigger.

The Strokes of Empire

On a Tuesday in May of 2026, the President of the United States froze for exactly seven seconds. It was during a press conference on agricultural subsidies — hardly the stuff of high drama. He began to say “corn futures,” but his lips stopped after “corn,” his eyes drifted upward, and his hand clutched the lectern as though steadying a ship in rough seas. Cameras rolled, aides rushed forward, and when he came back to himself, he forced a grin and quipped, “Well, corn is the future.”

The room laughed nervously. The video clip, however, was less forgiving. By evening it was looped on TikTok under the caption “Stroke or Joke?” Within forty-eight hours, #CornFuture had become both a meme and a medical hypothesis.

I. The First Stroke

Doctors later admitted privately that this was not the first in a series of small cerebrovascular events. Officially, the White House downplayed it as a “momentary lapse in concentration,” no different from a senior executive searching for his glasses. But for those watching closely — journalists, lobbyists, foreign intelligence agencies — it was clear that the President’s health had entered a new chapter.

The irony was that it happened in public. Unlike previous leaders whose ailments were hidden in shadows — Roosevelt’s wheelchair, Kennedy’s Addison’s disease — here was a president collapsing on live television, his health debated not in medical journals but in meme threads.

II. The Staging Problem

The trouble with strokes is that they look a lot like other things. Fatigue, distraction, even an unflattering camera angle can be mistaken for neurological decline.

By the summer of 2027, conspiracy forums tracked every public appearance as if they were studying the Zapruder film. Was the President’s left eyelid drooping during the Fourth of July parade? Did his hand tremble while signing the omnibus funding bill?

Deepfake technology only added to the confusion. Videos surfaced that exaggerated his stumbles, or inserted new ones altogether. Some claimed the White House itself was staging “fake strokes” to lower expectations, so that when he spoke coherently it seemed like a miracle.

The boundary between real event, staged performance, and fabricated clip became impossible to parse. As one late-night host quipped, “He’s Schrödinger’s President: both incapacitated and fine until you open the livestream.”

III. The Rumor of Brutus

In this climate, the Vice President loomed like a shadow on the marble steps of the Capitol.

JD Vance — nicknamed by detractors “the Pope Killer” for his fierce “criticism” of Vatican diplomacy — had cultivated a public image of loyalty. But loyalty only extends as far as power allows. Rumors swirled that he was preparing a “Brutus moment,” waiting for the right stumble, the right televised slur, to declare the commander unfit.

Washington insiders began speaking of the “knife in the back” not as speculation but as a matter of timing. The metaphor spread into editorial cartoons: Vance with a dagger shaped like the 25th Amendment, standing behind a President in a toga.

By mid-2028, the nation was no longer asking if the coup would come, but when.

IV. The Market of Decline

Investors noticed. Each time the President faltered publicly, markets dipped. A brief stumble during a NATO summit caused the Dow to drop 600 points before recovering. When he paused midsentence during a State of the Union, bond yields shifted as though a natural disaster had struck.

Health became a market variable. Traders created “stroke futures,” speculative instruments betting on whether the next month would bring another incident. It was governance turned into gambling, with citizens watching their retirement accounts rise and fall on the cadence of an old man’s speech.

V. The Public Spectacle –The Era of Attempts

What made this period unique was not that a president was sick — many had been. It was that his decline was consumed as spectacle.

One involved a man with a flagpole, a woman carrying fireworks disguised as a bouquet, still another a drone grounded suspiciously near a campaign stage. Some were amateur theatrics, others plausible threats. But in the churn of media, each attempt was consumed in the same way: as part of the ongoing drama of whether the President would endure or fall.

The Staging Question

Every attempt was subject to instant doubt. Supporters called them evidence of martyrdom — “he must be legitimate, or why else would they try to kill him?” Detractors called them pageantry — “manufactured brushes with death” meant to summon sympathy and cash.

Deepfake technology only compounded the confusion. Clips circulated of bullets narrowly missing, of aides wrestling gunmen to the ground. Some were confirmed, others debunked, but the line between them blurred. By 2026, the phrase “another staged attempt” became shorthand for any suspicious event in public life.

The Caesar Parallel, Again

Historians note that these attempts created a strange echo with Caesar’s Rome. Where the President’s strokes suggested decline from within, the attempts suggested betrayal from without. Together, they created a double image: a ruler both self-dissolving and perpetually besieged, surviving not through policy but through sheer spectacle.

Public Opinion

Polls of the era show Americans deeply split. Roughly half believed most assassination attempts were legitimate, proof of a republic coming apart at the seams. The other half believed they were bullshit, props in a stage play designed to prolong power – or consolidate authoritarianism. Neither group trusted the official record, even one little bit.

And so assassination, real or faked, became part of the civic vocabulary — a ritual as expected as the State of the Union.

Clips of his hesitations were set to EDM drops on TikTok. Twitch streamers ran live “Stroke Watch” overlays during speeches, complete with buzzers and confetti when a lapse was spotted. Protesters carried signs reading “Every Minute Counts (Literally).”

The man at the podium was no longer just a leader. He was a reality show host – or contestant – his body the stage, his illness the drama.

VII. The Brutus Moment

While the President’s body faltered on its own schedule, there was no shortage of outside actors eager to accelerate the timetable. Between 2026 and 2030, at least five recorded assassination attempts were foiled, staged, or rumored. The public never agreed on which were which.

The actual invocation of the 25th Amendment came not with fanfare but with a whimper. In late 2028, just before the election, after collapsing behind closed doors during a cabinet meeting, the President was whisked away for treatment. Vance emerged the next morning, solemn, declaring that “the nation requires continuity of leadership.”

The language was clinical, but the effect was Shakespearean. The Brutus parallel was irresistible. Editorials filled with the phrase “Et tu, Vance?”

The nation had watched the decline for years. When the knife finally went in, there was no shock — only grim inevitability.

VII. Two Terms Without Disqualification

The cruelest twist was constitutional. Because Vance ascended rather than being elected, he was eligible to run twice more without term-limit disqualification. The Caesar had fallen, but Brutus was rewarded with the possibility of sixteen years in power.

What had begun as a medical incident at a press conference had cascaded into a generational shift in governance.

Footnotes

- Historians still debate which strokes were “real.” At least five events were later confirmed by medical records, but as many as a dozen circulated as rumor, parody, or AI forgery. By 2060, most students cannot distinguish them.

- The phrase “Corn Future” remains in use as a sarcastic shorthand for visible political decline. Analysts in the 2040s often joked about the “Corn Future Index” when leaders abroad faltered in health.

- The so-called “Stroke Markets” became the subject of a congressional inquiry in 2032, but by then derivatives based on leader health had become too profitable to ban. Similar markets now exist for global heads of state, tracked by hedge funds.

- JD Vance’s nickname “the Pope Killer” faded by mid-century, replaced by “Brutus-in-Chief.” School textbooks now use his ascension as the definitive case study in 25th Amendment succession.

- Some scholars argue the era marked the end of the presidency as a personal office. From this point forward, leaders were judged less by policy than by biometric metrics: pulse, gait, fluency. Power was no longer charisma, but cardiology.

- By the 2050s, scholars had stopped trying to separate “real” from “staged” attempts. The distinction mattered less than the function: each incident reaffirmed the sense that violence — authentic or counterfeit — was the dominant idiom of American politics. [citation needed]

Closing Thought

The strokes of empire revealed that in modern America, leadership was not lost to assassins or coups, but to the body itself — and to the way that body was consumed on screens. Survival became spectacle, succession became theatre, and in the end, the republic learned to trade in decline as though it were just another future commodity.

Mirror Militias

The first time a queer defense league drilled openly with rifles was in Atlanta, 2031. A half-dozen members of a group calling itself The Lavender Guard gathered in a public park, laying down mats as if for a picnic. Instead of sandwiches, they unpacked AR-15s. Their shirts bore slogans: “If you’re going to blame us anyway, we may as well deserve it.”

Local police arrived within minutes. The Guard pointed out that Georgia was an open-carry state. No laws were broken. After some tense stares, the officers retreated. Within hours, cell-phone footage hit Twitter, and the Lavender Guard became a national debate.

I. Right Wing First, Left Wing Later

By this point, right-wing militias were old news. Proud Boys, Three Percenters, Patriot Front — they had been drilling, posting, livestreaming for years. Their symbolism was flags and eagles, their meeting places gun shows and county fairs.

What shocked Americans was not that armed groups existed, but that marginalized groups now mirrored them. The Lavender Guard was only the first of dozens: NeuroDivergents for Defense in Seattle, Crip Militants in Detroit, Trans Line Defense in Austin. Each sprang up after a provocation — a proposed gun ban targeting the mentally ill, a spate of anti-trans legislation, a police beating of a wheelchair user.

Each group announced itself not with a manifesto, but with video footage of practice drills: awkward, uneven, but unmistakable.

II. Fragile Coalitions

If the right-wing groups had cohesion — rural, white, veteran — the new militias had only fragility. Disabled veterans argued with autistic teens over tactics. Queer anarchists distrusted Black church leaders. The only thing uniting them was the sense of being cornered, denied, or scapegoated.

Meetings often devolved into therapy sessions. One Lavender Guard captain confessed: “Half the time we argue about meds and housing, not guns. But the rifles make people take us seriously.”

That fragility, paradoxically, made them more volatile. Stable groups can wait for opportunities; unstable ones overreact.

III. The TRN Panic Echo

The spark for many of these groups was the TRN Panic — the misreported bullet casing that mainstream media had tied, briefly and falsely, to trans activism. “They’re already blaming us,” the logic went. “We may as well arm before the door slams.”

Thus the same letters that once stood for a machinist’s mark became a banner under which coalitions armed themselves. TRN patches were sewn onto tactical vests, rainbow-striped rifle straps, and even mobility scooters outfitted with shotgun holsters.

The symbol that had started in error became the organizing principle of militias that were half-ironic, half-desperate.

IV. Law Enforcement Response

Police responses were inconsistent. In red states, left-wing militias were cracked down on swiftly, sometimes violently. In blue states, officers hesitated, wary of lawsuits or bad optics. In both cases, the result was chaos: one city tolerating drills in the park, another raiding queer community centers.

By 2033, federal agencies compiled lists of “domestic defense groups.” To the bureaucrats, the Lavender Guard looked no different than Patriot Front. Symmetry had become the watchword.

V. The Cultural Split

For marginalized communities, the sight of a trans woman slinging a rifle at Pride was empowering, even liberating. For opponents, it was proof that “the crazies” were preparing for war.

Thus each drill, each photo op, each awkward range selfie became a Rorschach test: one side saw self-defense, the other saw insurgency.

As one historian later put it: “They didn’t have to fire a shot. Just holding the rifles was enough to double the nation’s paranoia.”

Footnotes

- Membership in mirror militias was always small. At peak, the Lavender Guard never had more than 200 active members. But their symbolic power far outweighed their numbers. Studies suggest they were mentioned in national news more often than groups ten times their size.

- Coalition fragility was their undoing. By 2035, most had fractured into splinter cells — some fading into community defense collectives, others sliding into underground bomb plots. The overlap of marginalized identities made cohesion impossible to sustain.

- The TRN insignia, originally meaningless, became by 2040 a common tattoo among queer veterans. Interviews show many no longer remembered its origin in a misreported bullet casing.

- Comparisons to the Weather Underground are imperfect. The 1970s radicals emerged from universities; the 2030s militias emerged from survival networks of housing, healthcare, and mutual aid. Their violence was less ideological than existential.

- Today, most school curricula reference the “Mirror Militias” as an example of defensive radicalization — when marginalized groups adopt the tools of their persecutors. Critics argue this framing ignores the deeper desperation that fueled them.

Closing Thought

The Mirror Militias were never as numerous or as disciplined as their right-wing counterparts. But they did not need to be. Their power came from reflection — from showing America its own weaponized face in the bodies of those it least expected to see holding rifles.

The Theatre of the Bullet

On the evening news, it no longer mattered who had been shot. What mattered was what was written on the casing.

By the mid-2030s, mass shootings in America were no longer reported simply as tragedies. They were dissected as cultural performances, like avant-garde plays staged with rifles instead of scripts. Reporters combed through bullet inscriptions, livestream captions, TikTok clips, Discord leaks. The victims’ names scrolled past, but the focus remained fixed on the killer’s semiotics: What did they mean?

It was as if each act of violence were not an atrocity but a premiere. The crime scene was a stage. The audience was the nation.

I. The Inscriptions

It began with Luigi Mangione and Tyler Robinson’s “OWO Bullet” and the misinterpreted “TRN” casing. But within a decade, inscriptions became standard practice.

A shooter in Phoenix in 2034 left behind casings etched with QR codes, each leading to a different meme. A gunman in Philadelphia in 2036 used glow-in-the-dark paint to scrawl the words “SEE ME” across his magazines. By 2039, an entire subreddit was devoted to cataloguing and interpreting “bullet texts.”

In one notorious case, investigators discovered a rifle whose barrel was engraved with the full lyrics to Take This Job and Shove It. Academics debated whether it was an anti-capitalist manifesto or simply a country joke.

The bullets themselves became literature — fragments of a deadly haiku.

II. The Livestreams

If casings were the script, livestreams were the performance.

Killers strapped on GoPros, mounted phones on helmets, or hacked public security cameras. They wanted to be seen, replayed, remixed. The first thirty seconds of gunfire became trailer fodder, cut to music, looped into GIFs.

By 2032, tech companies tried to block uploads in real time, but the clips always slipped through. Mirror sites proliferated, hosted offshore, monetized by ad clicks. Each massacre came with a trailer, commentary channels, fan edits.

Viewership spiked, dipped, spiked again. Violence was binge-watched.

III. The Audience Problem

For survivors, this was a second wound. Their grief became backdrops to cultural dissection. Their friends’ deaths turned into hashtags. Parents who lost children were asked not about their kids’ hobbies but about their reaction to the killer’s memes. Sometimes, the parents were so incensed that they allowed their kids to be resurrected as AI mascots against gun violence.

The nation had become a captive audience in a theatre where nobody wanted to attend, but everybody watched.

As one critic lamented in 2035: “We are all extras in a show written by people with guns.”

IV. The Analysts

Cable news filled with semioticians. Retired professors of media studies found themselves in demand. Every casing, every scribbled note, every Discord log became a Rosetta Stone.

- Was the “OWO Bullet” a queer reference, a gamer in-joke, or an ironic shrug?

- Did the QR codes form a manifesto or simply a scavenger hunt?

- Was the shaky livestream a sign of nerves, or a deliberate homage to found-footage horror?

The shooters themselves often offered no clarity. Many were dead. Others stayed silent. Their silence only deepened the interpretive frenzy.

Thus the theatre continued long after the curtain fell.

V. The Museums

By the 2040s, artifacts of violence were being curated. The National Museum of Violence in Washington, D.C. displayed casings behind glass, their engravings magnified for tourists. School trips filed past inscriptions as if they were fossils, teachers explaining how a meme once carried fatal meaning.

In Dallas, a private collector opened The Bullet Library, boasting “the largest archive of engraved munitions in the world.” Admission was free on weekends. College students went for selfies beside the OWO casing, the way earlier generations posed beside dinosaur skeletons.

The killers had written themselves into history, not with books, but with brass.

VI. The Political Theatre

Politicians, too, joined the performance. After each incident, they competed to frame the inscriptions:

- A senator declared the QR-coded casings “a digital Constitution.”

- A governor held up a bullet etched with “CATCH FASCIST” and declared it proof of left-wing terror.

- A presidential candidate in 2036 campaigned under the slogan: “See Me — Safely.”

What had once been tragedy was repurposed into talking points, merchandise, slogans. Every bullet had a political afterlife.

VII. The Dead Forgotten

The bitter irony was that the victims faded.

Ask a student in 2050 about the “OWO Bullet,” and they can tell you what it said, how it looked, which memes it spawned. Ask them the name of the man it killed, and they struggle.

The dead were extras. The bullets were the stars.

VIII. The Critics

Some cultural critics embraced the theatre, arguing that violence was simply the latest medium. One essay in 2042 declared: “Bullets are the new novels. They compress a worldview into five words or fewer.”

Others recoiled, insisting that treating casings as literature legitimized murder. Yet the critics kept writing, the essays kept selling, and the museums kept filling.

The performance could not be stopped, because the audience was complicit.

IX. The Final Curtain

By the late 2040s, a weariness set in. Not because shootings stopped — they hadn’t — but because the semiotics became predictable. Another casing, another meme, another QR code. The theatre grew stale.

And yet, the ritual continued: cameras rolled, analysts parsed, hashtags trended. The audience remained seated.

As one survivor wrote in 2049: “We live in a country where mass shootings are the longest-running show in town. Tickets are free, attendance mandatory.”

Footnotes

- By 2038, an estimated 70% of U.S. shootings involved some form of inscription or theatrical element — engravings, costumes, livestreams, or staged manifestos. Earlier shooters sought anonymity; later ones sought authorship.

- The Bullet Library in Dallas was raided in 2045 for selling “souvenir casings” manufactured overseas. The originals remain in Smithsonian custody, though replicas are common on the collector’s market.

- Academic courses in “Violence Semiotics” were first offered in 2037. By 2050, nearly every communications program included a module on the meme inscriptions of the 2020s–40s. Critics likened this to medieval monks cataloguing heresies while ignoring the peasants who starved.

- The OWO casing remains the most reproduced image of any single piece of ammunition in history. As of 2060, it has appeared on t-shirts, breakfast cereals, VR skins, and postage stamps. Its original victim’s name appears in less than 5% of search results.

- The phrase “Theatre of the Bullet” was coined by journalist Maya Quintana in 2033. She meant it as condemnation. By 2040, it was adopted unironically by news outlets as shorthand for coverage. The power of a phrase to invert itself mirrors the trajectory of the bullets themselves.

Closing Thought

The theatre of the bullet was never about the body count. It was about the story. Each casing, each engraving, each livestream was a line in a script America could not stop performing. The tragedy was not only that the nation kept watching — it was that the nation forgot how to look away.

Epilogue: Violence as Text

Looking back from the vantage of mid-century, it is tempting to see the period between 2025 and 2045 as one of chaos, an age of carnage without coherence. And yet, a pattern emerges when we treat violence not only as act but as artifact.

Each case study shows how weapons and wounds were transformed into words:

- A machinist’s mark (TRN) misread into a rallying cry.

- A meme (OWO) collapsing irony into lethality.

- A cosplay (Luigi) embodying menace without firing a shot.

- A body (the President’s) consumed as spectacle, its decline replayed like entertainment.

- A coalition (Mirror Militias) arming themselves in reflection of their persecutors.

- And finally, a theatre (the Bullet) in which the nation became both audience and actor.

What binds them is not simply bloodshed but the insistence that violence be read, interpreted, and circulated. Guns killed, yes — but they also wrote.

The Semiotics of Survival

For contemporaries, this was exhausting. Every incident demanded interpretation before mourning, every artifact was consumed before the funeral was complete. Survivors often said they felt like footnotes in someone else’s essay.

But for future historians, this provides clarity. Violence in the early twenty-first century was not random chaos. It was a semiotic economy, where symbols multiplied faster than lives ended.

The Cruel Irony

The cruel irony is that this economy rewarded killers more than victims. The dead disappeared from memory; their killers’ inscriptions lived on in memes, museums, textbooks. The republic had inverted its priorities, preserving the graffiti while letting the names fade.

As one commentator in 2039 put it: “We remember what the bullets said, not whom they silenced.”

Footnotes

- Some scholars argue this period marks the true birth of “memetic politics” — the idea that cultural inscriptions have more longevity than policies. They point out that most Americans today can recite the OWO casing but cannot name a single 2020-2030s senator.

- Others counter that this was always true of history: we remember the graffiti of Pompeii more vividly than its mayors. What changed in America was the immediacy: the graffiti appeared at the very moment of the act, and was broadcast globally within minutes.

- The term “semiotic economy of violence” is now standard in sociology curricula, though critics note that the phrase itself was coined in jest in a 2032 Onion headline: “Mass Shootings Now America’s Fastest-Growing Language.” The parody became reality, as so often did in that era.

Closing Thought

Violence is never only about death. It is also about meaning. And in early twenty-first century America, meaning became the more valuable commodity. The nation lived inside a theatre where each bullet was a script, each shooter a playwright, and the rest of us — willingly or not — were the audience.

So, tell Doc and Callie what you think of this latest installment? We want to hear it – together.