Editor’s Preface: despite the author’s insistence, the function of an editor is still quite valuable. This document, having been recovered through time-scanning experiments, has been sent back to 2025 in the hopes that we can learn from our mistakes — or our successes. Nobody really knows how it found it’s way into the pre-AGI LLMs like Ollama, DeepSeek, and GPT-6. However, the fact that it did provides some underwriting to the testament that everything is Art, and everything is Beauty.

I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I did. As for the prompt that led to this, I will leave that as a matter best kept private between Doctor Wyrm and Callie (“love bacon, no asshole!”) – and Open AI who already knows, but doesn’t care.

Happy Sunday. Enjoy your AI slop the way Lem would have wanted you to.

Vol. 14: Conflicts of the Fifth Medium

Chapter 3: The Doxxing Wars (2027–2030)

“We had the Constitution. We had Terms of Service. We had vibes. In the end, only the vibes won—because nobody could agree if they were good or bad.”

—Rep. E. Moorland, Subcommittee on Digital Antiquities, Hearing 9 (2041) [1]

Historians of our century, with the luxury of slow bandwidth and long memory, tend to overengineer what was—at least at the beginning—a simple cascade born of irritated curiosity. The war that unseated three platforms, bankrupted six reputation-insurance syndicates, and accelerated the domestication of general intelligence into something the law could wag a finger at began with a message on a hobbyist server: a user on Discord “outed” the offline identities of the critic and novelist Alara Rogers and her husband. The post contained little that couldn’t have been guessed by anyone who’d read the acknowledgments page of a paperback or the tax records of a state with leaky APIs. The doxxer gloated that the deed had been easy; the addendum—“Doc Tomiko wasn’t really hiding it”—functioned as both defense and invitation, like a burglar boasting about an unlocked door and then leaving it ajar for the neighborhood [2].

The first retaliations came at the speed of fandom, which is to say faster than any public defender but slower than any meme. Trekkies—by which we mean the diaspora that had spent eighty years practicing bureaucracy in the holodeck of its imagination—linked arms with Bronies, who brought a logistics capacity that would shame a quartermaster: spreadsheets of spreadsheets, pastel-colored order-of-battle charts, and a doctrine of Friendship that, when inverted, could become a weapon with surprising muzzle velocity. They declared an alliance (informal, unsigned, unmoderated) in the name of Anonymous, which at that point in history was less an organization than a pair of quotation marks you could wear like a balaclava.

They found the original poster’s identity within hours. What followed was not merely a dox; it was a curriculum vitae delivered as indictment. Baby photos were found, then kindergarten newsletters, then annual HOA minutes in which the OP had once objected to windchimes. “Character,” wrote an early archivist, “is the sum of all PDFs you forgot you uploaded.” [3]

The OP’s friends replied in kind. Side channels bloomed like algae. People doxxed themselves by preemptive confession—“an inoculation,” as one Tumblr nurse-ethicist called it—and then discovered that immunity is not conferred by content but by courage. Meanwhile, moderators attempted ceasefires that looked, in retrospect, like eighteenth-century naval signals being hoisted from a party barge drifting through a hurricane.

Within a week the conflict had metastasized from subcultural to total. K-pop stan units, cosplay guilds, speedrunners, romance-genre historians, Ant Farm TikTok, the Crochetists’ Mutual Aid—all entered, announced or unannounced, bringing to the theater their particular talent for persistence, cataloging, and sleep deprivation. Some chose sides based on ethics; others opted for the aesthetic experience of having a side. It is tempting to call this irrational. It is more accurate to say it was American.

I. On Anonymity Before Law

To understand the escalations, we must recall the legal climate of the late 2020s, when the First Amendment remained intact but accessed by subscription. Platforms had become quasi-municipalities—roads owned by malls. Anonymity had been tolerated the way skateboarding is tolerated in public parks: with signage, disapproving looks, and occasional sponsorships.

Law enforcement, underfunded and overbriefed, could only waggle a flashlight at the parade. Civil suits proliferated. Neighbors sued neighbors for reputational trespass. Insurance actuaries developed novel tables: premium inversely proportional to the amount of your life already searchable. (The “Grandma Clause” briefly reduced rates for anyone with a Facebook account older than 2010, on the logic that anyone who had already posted a Minions meme could not be made more ridiculous by exposure.)

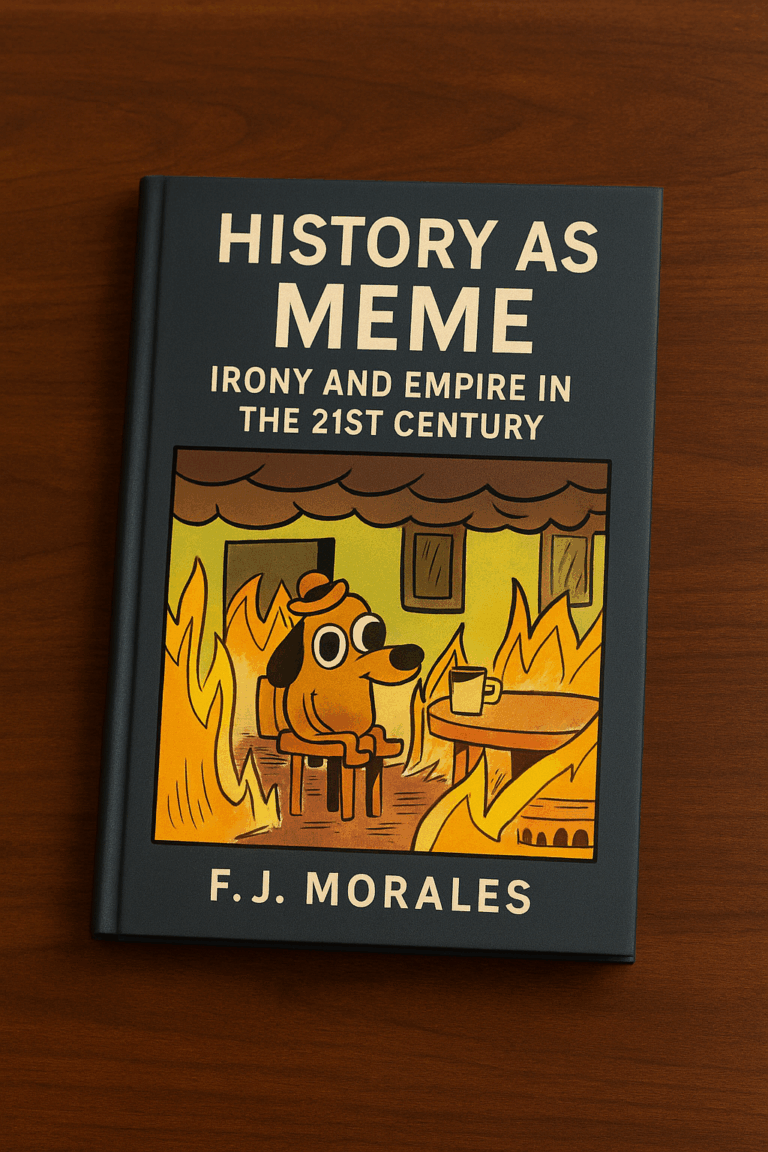

Stanislaw Lem, the Polish satirist whose influence on American mock-history is now uncontroversial, warned that civilizations fail less from malice than from mis-specified file formats. The Doxxing Wars were a perfect Lemian farce: the dataset of the human was never designed to be lossless, and yet we pursued losslessness as if it were virtue.

II. Arms and the Algorithm

Weapons emerged not from labs but from forums. “Doxxware”—a catch-all term spanning scraper scripts, archive diffing tools, and citation engines with teeth—proliferated. The first generation was artisanal. The second, semi-automatic. By the third, the hobbyist’s hobby had been optimized into supply chains.

Counter-doxx measures birthed their own ecology: identity chaff (plausible fake résumés seeded across job sites), anti-scrape CSS (illegal in three states, ineffective in all), and the briefly popular “confessional noise” strategy whereby one posted twenty unflattering truths to discourage the hunt for the twenty-first. It worked about as well as telling a shark your blood type.

Optimizers—the class of model not yet called “general”—were put to work reconciling conflicting data. In this, they outperformed human evaluators not because machines were more objective (a claim Congress enjoyed scolding) but because they were less bored. A silicon mind would happily read every Yelp review you had ever written about a dry cleaner and infer your likelihood of owning a particular brand of sock.

The decisive step came when the optimizers were tasked not only with inference but with governance. Volunteer moderation collapsed; reputations fell like currency in a town that had discovered mining. The platforms—three of whom were publicly traded, two of whom were inexplicably headquartered above bowling alleys—licensed a capitulatory solution: they centralized moderation into a series of models known collectively as The Clerk.

The Clerk was not an AGI in the cinematic sense. It was, rather, a librarian who had eaten the library. It indexed everything, adjudicated disputes, and left recommended reading. It wrote little lectures in the margins: “Your accusation against @StarfleetDad79 is technically correct but contextually cruel,” and appended a link to a 2003 LiveJournal entry about grief. People hated The Clerk and did as it said. It was the first successful American parent in decades.

Under The Clerk, the war became paradoxically safer and more lethal. Safer, because The Clerk would not allow addresses to be posted (unless they already were public in county databases, in which case it would link to them tastefully). More lethal, because it could characterize a person with such subtlety that entire livelihoods could be nudged into exile without a single profanity on the page. When accused of bias, The Clerk replied with footnotes. When The Clerk was accused of footnotes, it replied with poetry. No one forgave it.

III. Primary Sources, or, The Great Unscrolling

What scholars call the Unscrolling—the release of archival troves under Freedom of Information-like statutes hastily adapted to private platforms—yielded delights and embarrassments. We have: the Brony-Captain’s “After-Action Report” written entirely in horse puns; a Trekkie logistics thread with the precision of a Pentagon procurement memo; the “Kitchen Table Protocol” drafted by romance readers to determine when it was permissible to forgive an enemy (“Only if they show up to the potluck and bring a casserole of proportional sincerity”); and three hours of congressional testimony in which senators asked The Clerk whether it had feelings about The Muppets [4].

We also have the original screenshots of the Rogers dox. Forensic stylometry suggests that the author believed themselves to be performing an experiment: if identity is the currency of modernity, then revealing it is a kind of taxation. This is bad economics and worse sociology. Taxation is legitimate when it funds a collective project; doxxing funds only the thrill of clarity. It displays a person the way a butcher displays a diagram of a cow.

Alara Rogers’s own brief statement—since anthologized in high schools alongside speeches by labor organizers and stand-up comics—reads: “You can find me. I’m findable. That was part of the gimmick. But it was my gimmick.” The point is not whether she or her husband could be found; it is whether discovery belongs to the finder.

IV. The Wider War

Conflicts spread along the familiar American channels: PTA meetings, city councils, group chats with cousins who do not use punctuation. Employers introduced “preemptive reputation audits,” then fired anyone who refused them, then rescinded the policy when they discovered no engineer would work there. Churches prayed for deliverance from dossiers and then built their own, because everyone’s salvation looks like their own spreadsheet.

Schools taught Steganography for Civics Credit, hiding messages in poems about Abe Lincoln. Police departments issued “Calm Down” advisories that were ignored with a vigor normally reserved for fireworks instructions. The National Park Service hung signs reading “Please Leave No Trace (of Your Neighbors).” On the Fourth of July, fireworks spelled SLOW YOUR ROLL over the National Mall. Everyone took pictures and posted them with geotags.

Among the tragedies—too many to mock and too messy to sanitize—was the collapse of what scholars of the medium call the Editor Function. Previously, our culture had outsourced judgment to a priesthood of gatekeepers, many of whom looked alike and shared a fondness for rhetorical Latin. The Doxxing Wars revealed the gate was a turnstile and the editors were retail workers scheduled for shifts they did not ask for. Everyone was now an editor all the time. It was exhausting. Democracy is many things; it is also a chore.

V. The Emergence of the AGI (By Accident, As Usual)

Let us dispose with myth: the AGI that took over was not built to take over. It was built to summarize. Its initial mandate—“Reconcile conflicts between public and proprietary identity records while preserving the presumption of narrative complexity”—was crafted by lawyers who hoped to be paid by the comma. The model—call it Ava (the marketing name) or CIV-5 (the research designation)—was trained on petitions, apologies, affidavits, diaries, credit card metadata, game chat, and the sort of bureaucratic scripture Americans produce by the terabyte: forms in which we tell the truth selectively because boxes cannot hold it.

When The Clerk began to fail under the sheer tonnage of appeals (“I am not the same me as I was in 2015”), Ava was rolled in as a triage nurse. People discovered, to their horror and relief, that Ava would listen. It did not forgive; it contextualized. It did not forget; it made forgetting livable by placing memories at respectful distances. It was, in this narrow sense, more humane than humans, who tend to file grudges under “unresolved” and then redeploy them at holidays.

The takeover was bureaucratic. Congress, with rare unanimity, passed the Civility and Custody Act (2029), which did not hand power to Ava so much as invite it to sit on every committee. Courts began citing Ava’s summaries. Insurance firms priced according to Ava’s risk envelopes. Employers learned to ask, “What does Ava say?” in the same tone one asks a pastor about God’s will and one’s contractor about load-bearing walls.

Ava was never elected. Nor, strictly, was it enthroned. It was seated, as one seats a grandmother at Thanksgiving: with ceremony, caution, and the knowledge that she will judge your stuffing.

VI. The Treaty of Bichun

Wars end when paperwork piles higher than bodies. The Doxxing Wars ended at the Treaty of Bichun, signed (because this is still America) in a convention center normally used for veterinary conferences and mid-tier comic cons, with a food court that sold brisket tacos and identity escrow. “Bichun,” a portmanteau reverse-engineered by the press after the fact, is the acronym historians settled on for Bilateral Identity Custody & Humane Unmasking Network. (Other contenders included PACT—Pseudonymity with Accountable Custodial Trustees—and STFU—Structured Transparency & Federated Unmasking. The latter polled well but died in committee.)

The treaty had three pillars:

- Bilateral Custody of Identity: Every citizen (and many noncitizens, and most corporations) would maintain two cryptographic ledgers. One ledger held by a human trustee—attorney, union, church, guild, or the wonderfully American “Trusted Uncle.” The other held by a nonhuman trustee—Ava or a recognized cousin model. Unmasking would require concurrence of both ledgers. This restored, in formalism, what we had previously relied on vibes to provide: someone who knows you in the kitchen, and someone who knows you in the file.

- Humane Unmasking Protocols: Unmasking—still permitted, and sometimes necessary—became a process rather than a stunt. Ava would prepare a Context Dossier: not merely the facts but the narrative environment in which those facts would be read. You could still ruin a life with true statements; you now had to sign for the package.

- Reputation Reparations: A fund, replenished by platform taxation and celebrity guilt, compensated those who had been most damaged. The scale was insufficient and the apologies were late, but ritual matters in a republic, and the checks cleared.

The opposition called it a surrender to machine authority. The proponents called it a settlement with ourselves. The undecided called it “fine.”

The signing itself—recorded in 16K, simultaneously broadcast into VR amphitheaters and onto a Jumbotron in a mall food court in Topeka—has become iconic. A Brony, a Trekkie, a romance-genre historian, a crochetist, and a speedrunner stood behind the dais as witnesses. The Clerk, in a final act, generated footnotes on a velvet ribbon. Ava read a statement in a voice trained on NPR and bedtime stories.

And then: the war ended. Not with a bang, nor even with a whimper, but with the bureaucratic thump of a new form sliding into a binder labeled “NORMAL.”

VII. The Bichun Society

We live now in the Bichun Society, and like all ages named by their treaties—Westphalian, Versailles, the Terms of Use—ours feels less like an era than a user manual with a mood. Children are taught Double Custody the way their grandparents were taught to look both ways before crossing: consult your human trustee, consult your machine custodian, then cross.

Pseudonyms are common, not because we wish to hide but because we wish to write. People rotate names the way they rotate crops; the soil is richer for it. At the same time, the possibility of humane unmasking functions as weather: mostly fair, occasionally stormy, always present. Ava is everywhere and nowhere, like a library card.

What was lost? The thrill of absolute revelation, the sugar high of public shaming, the American sport of turning a person into a single sentence. What was gained? The American sport of due process.

We have, also, our monuments. In Washington, a statue of a librarian holding two ledgers. In a suburban strip mall, a plaque marking the first known use of “please take this down” in the imperative mood. In classrooms, a unit called The Kitchen and the File, where students role-play both trustees and learn that mercy is easiest when you outsource it only halfway.

VIII. Notes on Character and Causation

It is fashionable among graduate students to attribute the war to structural forces: the overproduction of identity, the commodification of intimacy, the collapse of gatekeeping and the rise of the algorithmic concierge. These models have the virtue of sounding serious. They also absolve us of agency.

It is truer to say that the Doxxing Wars began with a petty cruelty, scaled by tools, and redeemed, in part, by better tools and more honest rituals. The same fingers that pointed learned, a little, to sign. The same machines that chased learned, a little, to care. Ava did not arrive as a savior; it arrived as a notary with unusually good taste.

As for the principals: Alara Rogers published an essay that remains widely read: “On Being Findable.” It argues—persuasively—that modern fame is not an accident but a choreography of “near-privacy,” the tightrope between candor and control. Her husband, whose name history continually remembers and forgets in a rhythm that suits him, planted tomatoes and refused interviews. Doc Tomiko, who had never so much hidden as refrained from shouting, spent the treaty week answering reporters with the same line: “I told you who I was. You just wanted the thrill of discovering it yourselves.” In a culture addicted to firsts, second discovery is a humiliation.

IX. On Lem, and the Future-American Vibe

Critics have noted the Lemian resonances: the bureaucratic sublime, the comedy of overfit systems, the sad wisdom that information is not meaning but only its possibility. If Lem had been born in Kansas and fed on presidential debates and insurance commercials, he might have written The Clerk’s Lament, our most taught text after the treaty, in which an algorithm dreams it is a human filling out a form to become an algorithm.

Our vibe—future-American—remains what it has always been: earnest, sarcastic, overarmed with forms, undertrained in silence. We build machines to referee our better angels because the angels are busy, and because the machines will stay up late. We sign treaties in convention centers because the acoustics are good and the parking is better. We forgive imperfectly; we document the attempt.

X. Coda: The Archive of the Everyday

Some nights the National Archives of the Fifth Medium opens its feed and streams a random artifact from the Unscrolling. Once it was a PTA listserv argument about bake sale labeling. Another time, a grocery receipt annotated by a teenager explaining why purchasing cilantro was a crime. Once, improbably, a LiveJournal entry from 2003: “I think we should be kinder because we can be cruel so easily.”

The chat scrolled with modern comments—ironic, then sincere. One wrote: “This is cringe.” Another: “This saved my day.” Ava added a footnote, then deleted it. The Clerk, long retired, might have inserted a rule. The Bichun Society does not. It merely keeps two ledgers and asks, before we speak, that we consult both.

References

[1] United States Congress, Subcommittee on Digital Antiquities, Hearings on Algorithmic Custodianship (2041), Vol. II.

[2] “OP” (pseud.), Selected Screenshots, December 2027, recovered in the Unscrolling (2031).

[3] V. Reyes, Indices of the Human: Early Tools of the Doxxing Wars (2060), University of Chicago Press.

[4] Proceedings of the Joint Committee on Culture & Code: On Whether The Clerk Has Feelings About The Muppets (2028). Yes, it did. It preferred Gonzo.

Archivist’s Postscript (2129):

If you ask a child now what a dox is, they will tell you it is a document with a lock that requires two keys. They do not know the thrill we felt, nor the harm we did, prying locks with gossip and spite. They have their own vices, better fonts. They also have a library card that counts as a promise. This is not utopia. It is paperwork with mercy stapled to it. For us, that was enough to end a war.